Pacific Campaign

Origins

Greenpeace’s Pacific Campaign was set up in November 1986 with two co-ordinators: New Zealander Bunny McDiarmid, who was based in the Greenpeace New Zealand office in Auckland, and American Sebia Hawkins, who was based in the Greenpeace USA office in Washington DC.

Greenpeace’s Pacific Campaign was set up in November 1986 with two co-ordinators: New Zealander Bunny McDiarmid, who was based in the Greenpeace New Zealand office in Auckland, and American Sebia Hawkins, who was based in the Greenpeace USA office in Washington DC.

Bunny McDiarmid had been a crew member on the original Rainbow Warrior during the boat’s Nuclear-Free Pacific tour in 1984-85. She had participated in the relocation of the Rongelap community in the Marshall Islands from their irradiated home on Rongelap to another more suitable island, Mejato. As part of the crew she had also taken part in a protest against the US Star Wars missile system at the testing range at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands in June 1985.

After sailing on to Kiribati, Vanuatu, and New Zealand, the Rainbow Warrior had been due to lead protests against the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme at Moruroa Atoll in French Polynesia/Te ao Maohi. After the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in downtown Auckland on 10 July 1985 by French Government agents of the DGSE, she worked out of Greenpeace’s Auckland office and returned to live and work with the Rongelap community on Mejato for several months in 1986.

Sebia Hawkins was from Arkansas and had a background in the US Civil Rights Movement. After teaching history at the University of Maryland’s University College Adult Education Program in Germany, Italy, Japan, and the Philippines, she moved back to the US to work for Greenpeace USA’s Nuclear Campaign in 1984. She was actively involved with efforts to help the Government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands in its claims for compensation from the US Federal Government for the damage done by its nuclear weapons testing programme at Bikini and Rongelap during the 1940s and 1950s.

At the outset, both Bunny and Sebia knew that the organisation would need to evolve different ways of working in the Pacific region compared to the ‘traditional’ Greenpeace approach of direct action confrontation of environmental problems, so they set out to work collaboratively with local communities and public and regional institutions.

The Pacific Campaign umbrella had many spokes on it, from the nuclear testing and Star Wars missile testing issues through to climate change, marine protection, toxic waste dumping, and deforestation.

With two co-ordinators based in New Zealand and the USA, there was a natural degree of collaboration with those respective national offices, as well as the Steve Sawyer and the team at Greenpeace International, especially in the early years on French nuclear testing, US Star Wars missile testing, and driftnet fishing on the high seas.

Their modus operandi was to first develop and build a network of staff and contacts in the region. That led to the organisation of tours of Greenpeace staff and boats to raise awareness of environmental issues and influence the thinking and policies that shaped the way the environment was perceived and managed.

Greenpeace Pacific was also the first non-government organisation to apply for and be approved a ‘media representative’ pass for the annual South Pacific Forum Heads of Government Meetings, which meant staff were able to attend press conferences and press briefings during those meetings.

Culture and organisation

Looking back on the work of the Pacific Campaign during the period that she was a Co-ordinator, from 1987-1998, Bunny McDiarmid describes the history of that work being like beads on a thread: “The beads are the visible achievements or outcomes but the relationship building is the essential thing that links it all together and makes the beads possible.”

“For example, if you want to have a conversation or build a rapport with a prime minister in the South Pacific it’s important to talk about more than the environmental issue at stake. It is important to have some interest in their context such as knowing how their local or national rugby team did in their latest match. You need to make that sort of connection before you start talking about Plutonium shipments.”

“Relationships are a more important investment for people in the Pacific than investing in any bank. That means it’s important to work alongside people, so we invested the time in making those connections and that was one of the things that was so enjoyable.”

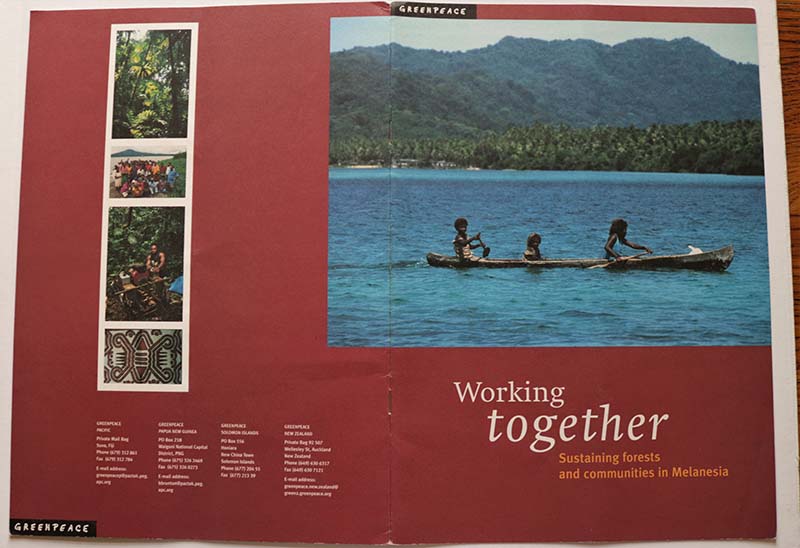

“Some of the most important work that Greenpeace did in the Pacific region in the 1990s was the ecoforestry project in the Solomon Islands and the Maisin tapa cloth project in Papua New Guinea.”

“Big Malaysian logging companies had started coming into Melanesia wanting to buy entire rainforests. Sometimes the local people thought that meant taking out some of the trees, but not bulldozing the whole rainforest, exporting the logs, then paying the central government a permit fee and keeping the rest of the money so that the local community saw very little of it.”

“That’s why we set up those two community projects. They were not just about protecting the trees in those rainforests; they were also about valuing and sustaining the local community whose land the rainforests were growing on and who lived from the abundance of their rainforests. That meant those projects were positive partnerships, which was different from the way Greenpeace was used to running its campaigns in other parts of the world. It was about being partners with local indigenous communities, rather than their ‘saviours’.”

“The internal connections that those projects helped to create between Greenpeace

Pacific, Greenpeace New Zealand, and Greenpeace USA also helped to shift how the wider Greenpeace network thought about campaigning.”

Putting climate change ‘on the map’

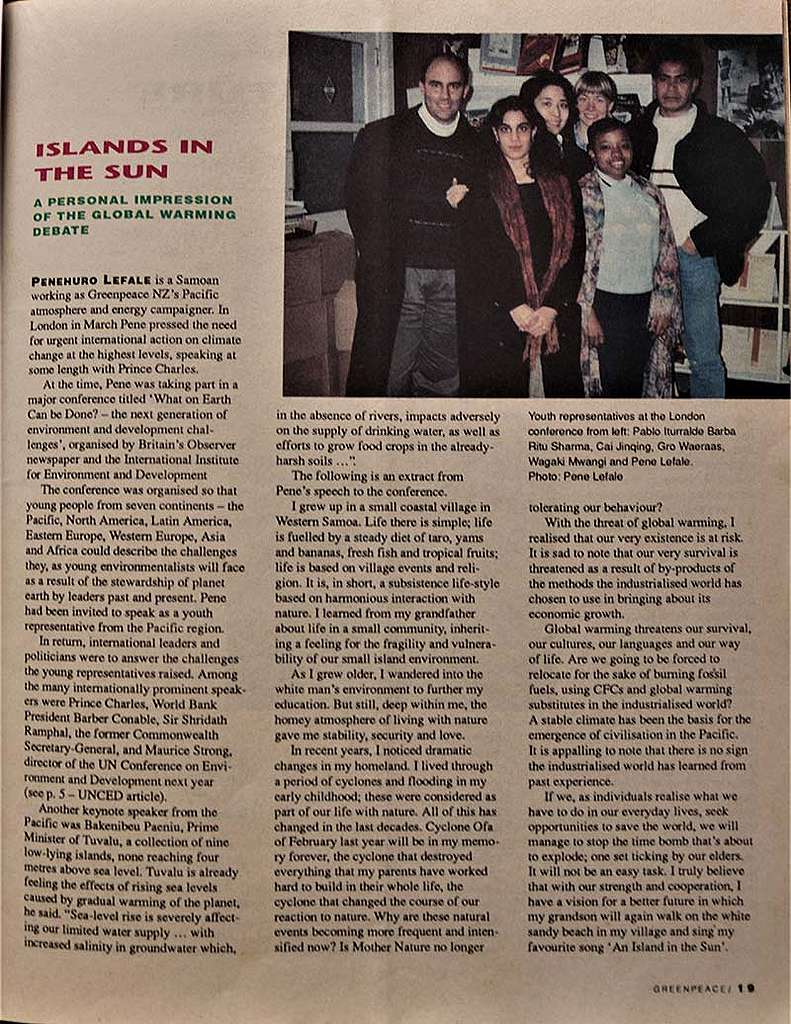

“Hiring Pene Lefale as our first Climate Campaigner in the Pacific in 1990 was a really significant step. He had grown up in Samoa and he had a science degree from the University of the South Pacific in Fiji. He was a unique voice within Greenpeace working on climate change in the Pacific at that time. He was also a pioneer. He could translate the science of climate change into the right language for working in the Pacific and he helped put climate change ‘on the map’ in the Pacific.”

“The work we did to raise awareness about coral bleaching was an important aspect of the campaign, as so many islands in the Pacific are coral atolls. The widespread understanding that they are the nurseries of the fish that people lived off and made their livelihoods from made this a compelling part of the climate story for many in the Pacific. This included collaborating with Ove Hoegh-Guldberg from the University of Sydney on various projects. Ove wrote a report for us about the issue and we helped distribute his survey documenting coral bleaching events in the Pacific, which contributed to a global database.”

Ban the Burn

“The campaign that Greenpeace Pacific ran in the early 1990s against the incineration of industrial waste at sea and the incineration of US chemical weapons stockpiles at Johnston Atoll in the Pacific was also important. Up to then there was an attitude among companies and governments from outside the region that the Pacific was a big wide-open space and the high seas were everyone’s domain where they could do what they liked.”

“The approach at the time was that the oceans are so deep, they can ‘dilute’ whatever we put in there. But scientific evidence was building against taking that approach.”

“The campaigns that we ran put more emphasis on the Pacific as the bread basket of the region and that with ‘rights’ to the use of the high seas came also the responsibility to protect it.”

“So, our campaign also contributed to the end of ocean incineration.”

Transforming oceans policy

“The Pacific Campaign also played a role in helping to shape future oceans policy. For example, Sebia Hawkins organised a ‘Freedom for the Seas in the 21st Century’ conference in Honolulu, Hawai’i, in December 1990 on oceans governance and environmental sustainability with the support of Greenpeace Legal Counsel Duncan Currie, Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Michael Hagler, and NZ environmental lawyer Grant Hewison.”

That conference, which was jointly sponsored by Greenpeace Pacific, the Centre for International Environmental Law, the Spark M. Matsunaga Institute for Peace at the University of Hawai’i, and the Peace Research Centre at the Australian National University, discussed potential future reforms of the international system governing the marine environment and promoted better protection of highly migratory species and fish stocks, marine mammals, and natural resources from exploitation, pollution, and military activities.

Participants also contributed to a book of the same name published in 1993, which included a chapter by Moana Jackson on ‘Indigenous Law and the Sea’ which advocated for indigenous people to have a role in oceans governance, invoking concepts such as Te Tikanga o te Moana and their role as Kaitiaki in nurturing and protecting the ocean as a living treasure or Taonga.

Pacific Ways

There was also a commitment in the Pacific Campaign to have Pacific Islanders leading and running the campaign work, and to work with Greenpeace’s Marine Division to ensure that Pacific Islanders were also included in the boats’ crews. Pacific Islanders who worked for the Greenpeace Pacific Campaign and/or on Greenpeace’s boats in the region included Pene Lefale, Tamsin Vuetilovoni, Nainasa Whippy, Maureen Penjueli, Anj Heffernan, Philip Pupuka, Lawrence Makili, Chris Shigetomi, and Tino Tetuanuitefarerii.

There were also long-standing connections with communities in the Marshall Islands through Giff Johnson, Steve Sawyer, Bunny McDiarmid, and Alice Leney; Tahitians opposed to the French Government’s nuclear tests at Moruroa Atoll through Bunny McDiarmid, Martini Gotje, and Stephanie Mills; with communities in the Solomon Islands through Grant Rosoman, Philip Pupuka, and Lawrence Makili; and in Papua New Guinea through Lafcadio Cortesi.

“Lafcadio Cortesi was a big driver of the local community work the campaign was involved with in Papua New Guinea. He was so loud and extroverted, yet also so attuned to what local communities were saying they wanted. He wanted them in the driving seat. Sebia really saw something special in Lafcadio when she hired him,” recalls Bunny McDiarmid.

“We were also having the same sort of conversation about ecotourism in Kosrae and Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia, where Greenpeace Pacific Pollution Prevention Campaigners Dave Rapaport and Jeanne Kirby worked together with teams of local people on a pilot project to demonstrate the viability of biological composting toilets as an alternative to water-based toilets, particularly in places where water was a precious commodity. That issue was also a big concern for local communities because water-based toilets would often overflow during heavy rain and pollute coastal waters, which were obviously important for local livelihoods.”

“Encouraging Environmentally Sound Tourism Development“, Dave Rapaport, Greenpeace Pacific, Ecotourism Business in the Pacific, Conference Proceedings, Auckland, New Zealand, October 12-14, 1992

“Back in the 1990s, development NGOs were becoming more ecologically-minded just as environment NGOs were becoming more community development-minded. Greenpeace Pacific was on the cusp of that discussion. That was important because there were some voices in the Pacific that claimed that environmentalism was a means to halting development. Greenpeace Pacific was saying that environmentalism wasn’t about stopping development, but questioning how to go about it, and how to develop forms of tourism and forestry that were ecological as well as community-owned and community-led.”

“Greenpeace Pacific’s Campaign strategies were all about context. We had to establish relationships first with local communities before we approached central governments. We had to understand their reality before we could develop strategies together. It was their neighbourhood.”

“Oral tradition is so much stronger in the Pacific and you have to identify both the formal and informal leaders. At the government level there were predominantly elected male leaders, but the leaders at the community level are not the same people.”

“We would provide information and approach government leaders and decision-makers, but we also worked with local communities to support grassroots voices being part of the debate. For example, in some parts of the Pacific corruption had become part of the decision-making with big companies accessing natural resources, and in those instances, we responded to requests from local communities to support and strengthen their capacity. In one case this meant supporting them to delineate their lands, so their legal hand was strengthened in protecting their resources.”

“Some governments also had the power to issue logging permits without the consent of local landowners, so the ecoforestry and tapa cloth projects were designed to ensure local control and local income in the face of that reality.”

“SV Rainbow Warrior II had a presence which was influential and inspiring in the region. When she arrived at a port it seemed she was the size of an ocean liner, so she was great for campaigning on the big environmental issues. She had a different kind of power to SV Vega and SV Redbill, which were smaller wooden boats that could do a different job and were often more suited to visiting smaller locations and their local communities.”

“Climate change is cultural genocide”

“I remember – around the time I went to the UN Climate Change Conference in the Maldives in 1988 – I went to see President Ieremia Tabai in Kiribati and we discussed the latest UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. Talking about it, he said to me, ‘Do you know what this means? In 50 years, my land will be uninhabitable. Fifty years after that my language will probably be gone. And 50 years after that my culture will no longer exist. Do you realise how hard that is for me to accept?’.”

“The reality is that the Pacific Islands are on the front line of climate change, they’re being hit by the impacts of coral bleaching, more extreme weather events, and sea-level rise and surges, yet they have contributed the least and have the least power to change it. Pene Lefale saw that political dynamic in the international climate negotiations and it was heart-breaking for him. As Tuvalu’s Prime Minister Bikenibeu Paeniu said about climate change back in the 1990s: ‘This is cultural genocide’.”

“The Pacific region also played a role in the wider Greenpeace climate campaign. Jeremy Leggett and Bill Hare at Greenpeace International were able to develop important relationships with people in the Pacific that influenced their work in the international arena.”

“I remember at the South Pacific Forum Heads of Government Meeting one year, the Australian prime minister at the time said, ‘It’s more economical for us to resettle Pacific Islanders in Australia than to change our energy and mining sectors’.”

“We were also up against the cynical and basically morally defunct view expressed by NZ Conservation Minister Nick Smith that, ‘If NZ doesn’t dig up fossil fuels and sell them overseas, someone else will do it anyway’.”

“And there were some back then who didn’t want to believe that a climate catastrophe was on the horizon.”

“During the campaign to stop the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme at Moruroa, we faced a single ‘combatant’. With climate change we were – and still are – up against the vested interests of the status quo, the long established world energy system and all the big fossil fuel companies.”

Collaborative campaigns and solutions

“Greenpeace had many notable campaign achievements in the Pacific during the 1990s such as ending driftnet fishing, ending ocean waste incineration, ending the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme, and ending the export of toxic waste into the region. None of this would have happened without the many others that we worked together with across the Pacific and beyond.”

“The Solomon Islands ecoforestry project, the Maisin tapa cloth project in Papua New Guinea, and the pollution prevention project in Kosrae and Yap were also important as examples of solutions-focused collaborations. Greenpeace Pacific also helped raise the profile of then emerging ‘new’ environmental issues on the regional agenda from climate change and Plutonium shipments to logging company practices and Japanese Government attempts to use aid funding to buy-off opposition to whaling.”

After nine years as a co-ordinator, Sebia Hawkins left the campaign in 1995, and was followed by Bunny McDiarmid in 1998. After that, its co-ordination was relocated to the Greenpeace Australia-Pacific office in Sydney where a new chapter started.

Sebia Hawkins continued her involvement as a member of the Greenpeace USA board of directors. She went on to work as Development Director for Collective Heritage Institute in New Mexico, the Ruckus Society in California, the Center for International Environmental Law in Washington DC, Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety in Santa Fe, and the Permaculture Credit Union in New Mexico. Her last job was as Director of Development for the Environmental Law Group of New Mexico in Santa Fe. Sadly, she died of cancer in 2012.

Bunny McDiarmid subsequently returned to become Executive Director of Greenpeace New Zealand in 2005, working in the role for ten years before being appointed as co-Executive Director of Greenpeace International in 2016 with Jennifer Morgan, where Bunny worked until 2019. Since then Bunny has been sailing around the Mediterranean Sea with her partner Henk Haazen in their ice-class yacht, SV Tiama.

“Greenpeace warrior Bunny McDiarmid retires”, Kim Knight, Stuff, 11 June 2015