Antarctic Campaign

Origins and expeditions

Greenpeace’s campaign to protect the world’s last pristine wilderness had its origins in a 1979 proposal. That progressed to the launch of a campaign for a World Park in Antarctica in the 1980s, led by New Zealander Roger Wilson at Greenpeace International, which set out to protect the continent from all mineral and fossil fuel exploitation.

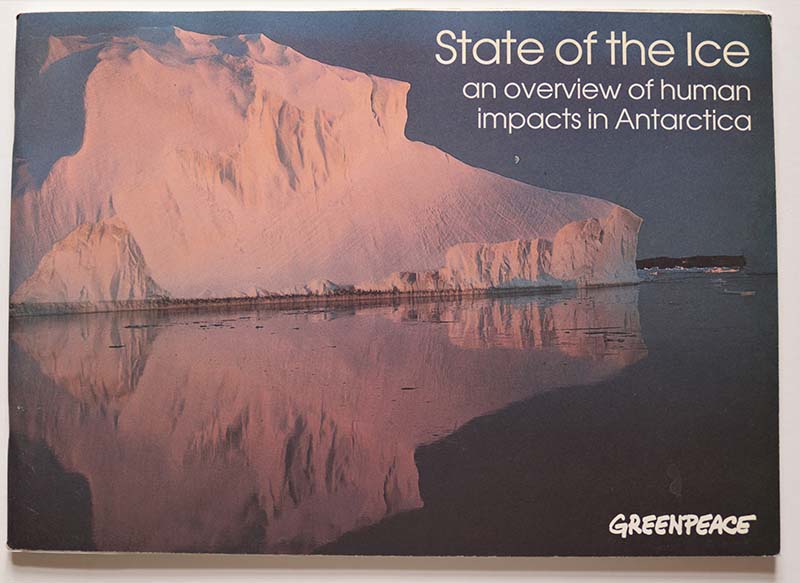

The Antarctic Campaign also had a strong focus on protecting the marine wildlife that lived in Antarctica and the seas around it, because of the potential threat posed by oil drilling and mining which was anticipated to commence under the proposed Antarctic Minerals Convention, CRAMRA.

Greenpeace sent its ice-class ship MV Greenpeace on an expedition to Antarctica in 1987, where it set up its World Park Antarctica Base, the first NGO base established there among dozens of national research stations. Henk Haazen was Logistics Coordinator on Greenpeace’s Antarctic expeditions at that time and Carol Stewart was Greenpeace’s New Zealand’s Antarctic Campaigner.

Greenpeace followed this with regular ship-based Antarctic expeditions by MV Greenpeace and MV Gondwana until 1992 to both survey national bases and resupply Greenpeace’s World Park Antarctica Base. As Greenpeace New Zealand itself grew during the late 1980s so too did the Antarctic Campaign. New staff Dr Allan Hemmings and Dr Maj De Poorter were hired to work on the policy and scientific dimensions of the campaign, and new Antarctic Campaigner Janet Dalziell and new Campaign Assistant Arani Cuthbert were also brought on board.

The expeditions enabled Greenpeace to monitor and document the impacts of the various national research stations on the continent’s coast and fisheries activities in the Southern Ocean. The Greenpeace World Park Base team there also monitored pollution and activities at the research bases located nearby.

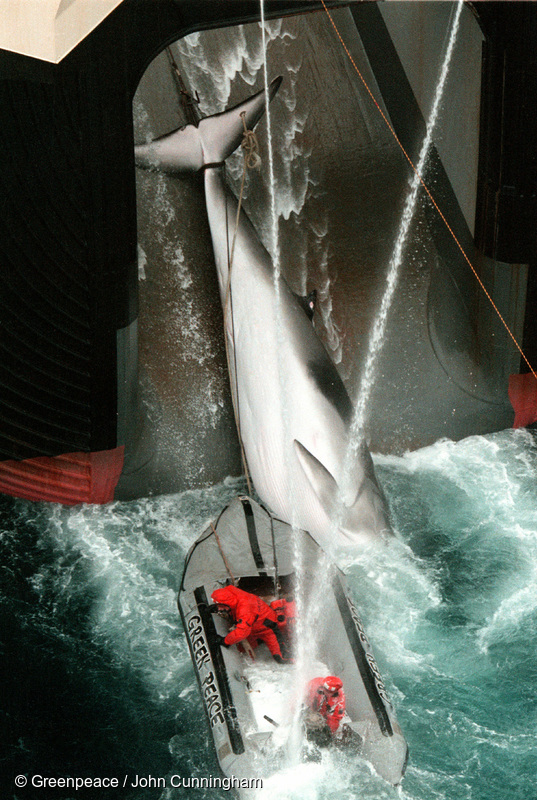

During these expeditions, Greenpeace also used its ice-class vessel MV Greenpeace, which was equipped with a helicopter and inflatable boats, to confront and disrupt the operations of the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet in the Southern Ocean.

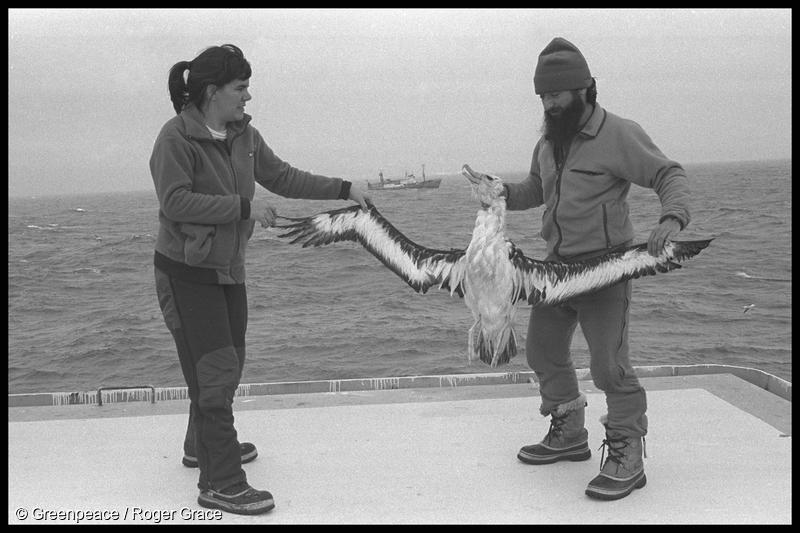

During February-April 1991, MV Greenpeace also tracked down and documented the activities of the Soviet Union’s large longlining and trawl fishing fleets that were targeting Patagonian Toothfish and Krill in the Southern Ocean. Video footage and photographs that Greenpeace submitted to the Antarctic Marine Conservation Convention (CCAMLR) was the first evidence that longline fishing operations in the Patagonian Toothfish fishery in the Southern Ocean was killing non-target albatrosses and other seabird species.

By submitting this evidence, Greenpeace Antarctic Campaigner Janet Dalziell was able to urge CCAMLR at its 1991 annual meeting to adopt stronger measures, such as requiring the use of seabird-scaring streamers on boats fishing within the CCAMLR zone and prohibiting fishing vessels from discharging fish offal into the water during the time they were fishing because it would attract more albatrosses to the baited hooks.

Greenpeace also submitted footage and reports documenting pollution and other impacts of the various national Antarctic bases to Antarctic Treaty meetings in order to hold governments to account for their activities and to persuade them to establish a World Park in Antarctica.

Victory in Antarctica

In New Zealand, Greenpeace successfully campaigned to end the Government’s support for the proposed Antarctic minerals convention (CRAMRA) and instead support full protection of Antarctica.

During May and June 1990 Greenpeace Antarctic Campaign Assistant Arani Cuthbert and Antarctic expedition crew member Phil Doherty travelled around the New Zealand on a six-week 25-stop tour of town hall meetings and local radio interviews from Christchurch to Whitianga taking in mostly smaller towns to help mobilise grassroots support for Greenpeace’s goal of a World Park in Antarctica protected from mining and oil exploration.

During the tour they encouraged people attending the meetings to tell their local MPs and candidates about their support for a World Park in Antarctica ahead of the October 1990 general election.

“I kept quoting Margaret Meade’s adage, ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world’,” said Arani Cuthbert. “The idea was to empower people, and the response was great.”

Janet Dalziell visited MPs and ministers in Wellington and in their constituencies to follow up with them after the interest generated by the tour. “I also spoke with Ed Hillary about the campaign and he later spoke publicly in favour of a World Park in Antarctica,” she recalls.

“The campaign had to focus on the NZ Government’s support for the CRAMRA minerals convention at the time,” she adds. “We were also able to show MPs and ministers that the risk of oil spills was real after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska and the Bahia Paraiso oil spill in Antarctica, and to point to the French Government dropping its support for mining in Antarctica as a positive example of a government putting the environment ahead of exploitation.”

The grassroots pressure, media interest, and lobbying work with opposition MPs and government ministers helped make protection of Antarctica an issue in the October 1990 election. Eventually the opposition National Party shifted its position and said it would not support the CRAMRA mining convention in Antarctica, so the Labour Government came under more pressure to drop its support for mining there.

Greenpeace’s other ice-class vessel, MV Gondwana, also toured east coast cities during August 1990, including port visits in Auckland, Nelson, Wellington, Napier, Gisborne, Tauranga, and Lyttelton.

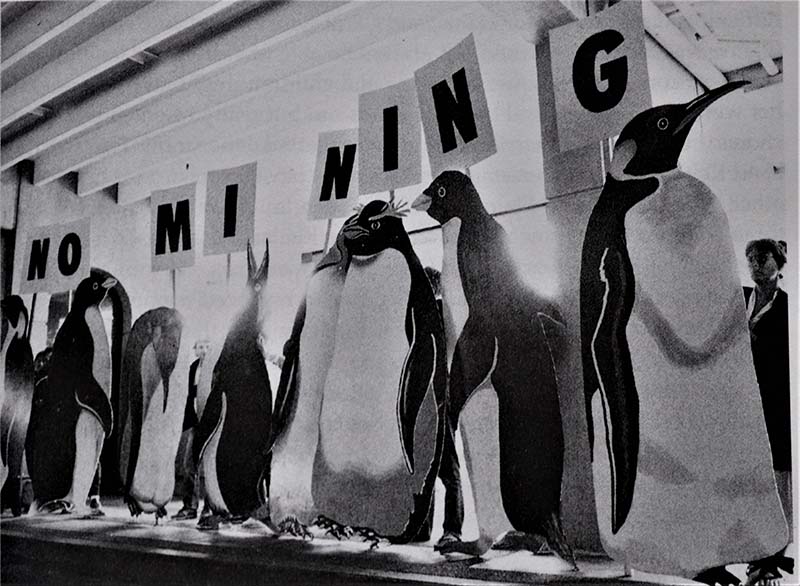

On 25 August 1990, NZ Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer met with Greenpeace campaigners and activists dressed in penguin costumes as they protested outside Parliament during MV Gondwana’s visit to Wellington. Later the same day, he announced that the NZ Government had decided to drop its support for mining and oil exploration in Antarctica.

Writing in the Greenpeace New Zealand members’ magazine shortly afterwards, Janet Dalziell said: “It is clear that public pressure has achieved these major changes in government policy in a very short period of time. The Greenpeace Antarctic campaign would like to pay tribute to all the people around the country who wrote letters to their politicians and to newspapers, who signed petitions, and posted postcards. … We have shown yet again that the weight of public opinion can make a difference – especially in election year.”

After Greenpeace’s seven year campaign, the Antarctic Treaty nations agreed a new Environment Protocol to the Treaty in June 1991 that included a 50-year ban on all mineral and fossil fuels exploitation in Antarctica. The Protocol also committed the signatories to “comprehensive protection of the Antarctic environment and dependent and associated ecosystems” and designates Antarctica as a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science”.

Later in 1991 Greenpeace removed its World Park Base and began to wind-down its base inspection expeditions to put more emphasis on protecting whales and the wider Southern Ocean ecosystem.

Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary

Greenpeace New Zealand then started campaigning for the creation of a huge Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary around the entire Antarctic continent. Greenpeace Campaign Manager Stephanie Mills and Mana Tangata Educator Nicola Easthope embarked on a land-based tour of North Island towns in April 1994 to encourage support from local communities and mayors of towns such as Whanganui and Napier that fell within the Sanctuary’s proposed boundaries.

After an international agreement to create a Sanctuary later that year, Greenpeace sent MV Greenpeace to confront the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet 1,200 kilometres inside the newly established Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary in the Ross Sea the following year.

Greenpeace released dramatic footage to the world’s news media of the MV Greenpeace’s crew driving inflatable boats and Greenpeace’s helicopter between the harpoon guns and the whales, preventing the whalers from killing more whales for several weeks and reducing the final number of whales killed.

Collapse of the Larsen ice-shelf

In 1997, Greenpeace sent its new icebreaker MV Arctic Sunrise to the Larsen ice shelf in Antarctica to explore the area for a month to document signs of climate change impacts. Expedition leader Janet Dalziell says the ship got to within two kilometres of Cape Worsley, a point that had been 47 kilometres from the edge of the Larsen A ice shelf before it collapsed in 1995.

The expedition gave scientists their best view yet of the seabed there, that had been previously hidden beneath Larsen A. Using an echo sounder, Greenpeace scientist Ricardo Roura and Jorge Lusky of the Argentina Antarctic Institute found and documented a channel more than 800 metres deep, some 15 kilometres wide, and 30 kilometres long which was filled with cold glacial meltwater, and which may have prevented the Larsen A ice shelf from collapsing earlier than it did.

Afterwards, Antarctic Campaigner Janet Dalziell and Climate Campaigner Adam Laidlaw presented the data gathered by the expedition at a Select Committee hearing in the NZ Parliament to help educate MPs on the unfolding impacts of climate change on the Larsen Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Just five years later in 2002, the Larsen B ice shelf partially collapsed and broke up, affecting an area of 3,250 square kilometres of ice that was 220 metres thick.

Southern Ocean pirate fishing

In March 2000 while scouring the Southern Ocean for pirate fishing vessels the crew of MV Arctic Sunrise found five kilometres of longline that had been abandoned by a pirate fishing vessel still with toothfish on it. Toothfish are so valuable they are also known as ‘white gold’. Crew aboard MV Arctic Sunrise, including five New Zealanders, released 60 toothfish that were still alive into the icy waters after unhooking them from the abandoned longline.

Up to the year 2000, pirate fishing vessels had poached an estimated 100,000 tonnes of toothfish in the Southern Ocean valued at NZ$1 billion. The same pirate fishing vessels were also estimated to have hooked and drowned between 60,000-100,000 seabirds in their fishing gear, including endangered species of albatross that bred on New Zealand’s Subantarctic Islands.

Saving Antarctic whales

In December 1999, Greenpeace’s MV Arctic Sunrise returned to track the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet that was illegally hunting whales inside the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary surrounding Antarctica and intervene to disrupt the harpoon guns.

Greenpeace continued to send its ships to confront and disrupt the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet in the Sanctuary through the 2000s into the 2010s, saving many hundreds or whales.

Then in 2014, the International Court of Justice voted overwhelmingly that the size and scope of the Japanese Government’s so-called “scientific whaling” programme was not driven by scientific considerations, and therefore all permits for it must be cancelled and no new ones issued. The ruling was a big win for the whales, after Greenpeace had campaigned against the Japanese Government’s whaling programme in the Southern Ocean for more than 20 years.

New Southern Ocean sanctuaries

In the 2010s Greenpeace also started campaigning for the establishment of large-scale ocean sanctuaries in the Southern Ocean to protect all marine life there from industrial-scale fishing fleets and pirate fishing, and to help protect the global climate.

A first step was the creation of a marine protected area in 2016 with varying degrees of use allowed in some areas and some areas fully protected. That resulted in more than 1.5 million square kilometres of the Ross Sea being protected under an agreement negotiated by the 24 CCAMLR countries and the European Union. An area of 1.1m square kilometres within it – about the size of France and Spain combined – is now designated as a no-take “general protection zone” where all fishing is banned.

Since then Greenpeace has campaigned for the creation of an even larger Antarctic Ocean Sanctuary, covering almost two million square kilometres, in the Weddell Sea region and off the Antarctic Peninsula to protect fragile ocean ecosystems and counter climate change.

Annual talks are held at CCAMLR every year in November but have so far failed to agree on the proposal. While 22 governments have supported the plan for a new Antarctic Ocean Sanctuary, those of Russia, China and Norway reportedly have not.

This just goes to show how important it has been for Greenpeace’s campaigns to be prepared for the long haul: Antarctica was protected in 1991, the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary set up in 1994, the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area agreed in 2016 – and hopefully the East Antarctica Ocean Sanctuary in the Weddell Sea will become a reality in the near future.

Greenpeace’s ice-class vessel MV Esperanza completed its most recent Antarctic expedition in March 2020, during which its crew and onboard scientists carried out a range of research, including environmental DNA sampling and surveying for plastic pollution at sea, and surveying penguin colonies there that are declining in the face of rising global temperatures.

Greenpeace’s agenda now in the Antarctic and Southern Ocean is to establish more ocean sanctuaries, stop plastic pollution, stop pirate fishing, protect the climate, and ensure that the 1991 ban on oil and mineral exploitation remains in place forever.