Agriculture campaign

The precautionary approach and ecological agriculture

Greenpeace started campaigning in the 1980s to protect freshwater and stop the production and use of toxic chemicals in New Zealand, including the toxic organochlorine herbicide 2,4,5-T, through the work of Gordon Jackman and Renate Kroesa.

When the Toxics Campaign was expanded in 1990, it included a new team member – Meriel Watts – who campaigned specifically against toxic pesticide use and for a shift to what was generally known then as ‘organic agriculture’.

In 1991 Meriel Watts produced a detailed document on “Ecological Agriculture in New Zealand”, which was the first time that Greenpeace had set out its vision of how intensive ‘conventional’ agriculture could be transformed into ‘ecological’ agriculture in New Zealand.

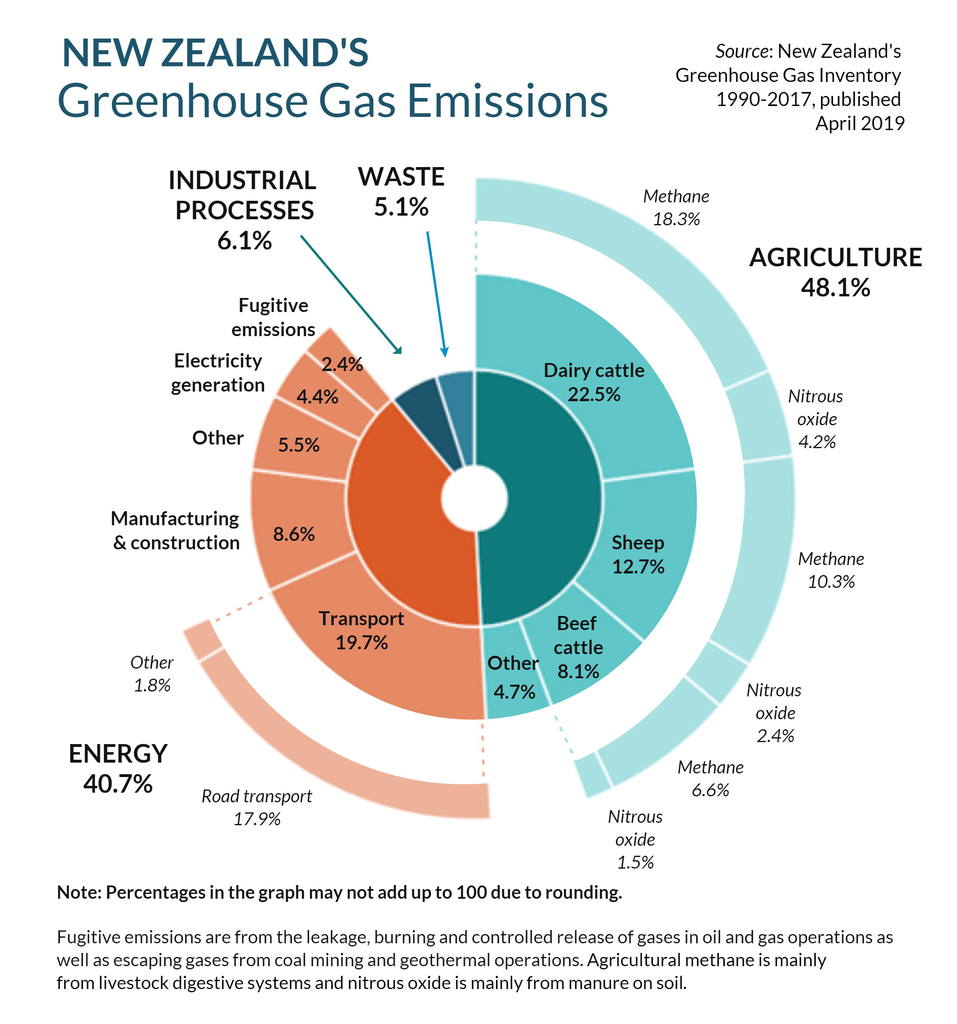

Agriculture was the largest sector of the economy in 1990, with major impacts on the environment caused by toxic chemical and fertiliser use, methane emissions from livestock, and carbon emissions from associated energy use. This also meant the sector had a major influence on government policy and funding decisions, especially through Federated Farmers and big companies in the sector such as Anchor (now part of dairy giant Fonterra).

At that time Greenpeace’s Pesticides Campaign had an important role educating the public and decision-makers about the harmful health and environmental effects of pesticides.

An early achievement was the inclusion of the “precautionary approach” in the 1996 Hazardous Substances & New Organisms legislation, after Greenpeace sent all MPs a green condom with the request to ‘keep the precautionary approach in the HSNO Bill’ at a time when there was a risk it would be removed during the Select Committee stage. It was not.

Greenpeace’s Mana Tangata Community Liaison Catherine Delahunty published a regular ‘Green Women’s Network’ newsletter as part of her work educating New Zealand communities about the health and environmental impacts of toxic chemicals in the 1990s. She also led a delegation from the Women’s Environmental Network to meet Associate Minister of Health and Women’s Affairs Katherine O’Regan to inform her about the impacts of chlorinated chemicals on women’s health and the environment, and urge Government action to ban their use.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Greenpeace turned its attention to campaigning for the NZ Government to sign and ratify the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). The UN Treaty, signed in October 2001, aimed to eliminate the so-called ‘dirty dozen’ organochlorine pesticides and cancer-causing dioxin. It entered into force in New Zealand in May 2004.

Palm oil and deforestation in SE Asia

Through the 2000s, Greenpeace increasingly targeted carbon emissions from the agricultural sector, especially the intensification of NZ dairying and the adjunct use of palm oil expeller (PKE) imported from South East Asia to NZ as a stock feed. Palm production also drives rainforest destruction in south-east Asia, further increasing the carbon footprint of NZ’s dairying sector.

In 2009, Greenpeace New Zealand helped blow the whistle on rainforest destruction in Indonesia being linked to the clearance of land to make way for palm plantations that produced palm oil and a livestock feed product called PKE that was being imported into NZ in huge quantities to feed cows.

A Greenpeace New Zealand team led by Communications Manager Suzette Jackson travelled to Sumatra, Indonesia, accompanied by an independent journalist and an independent NZ farmer to document the devastation wrought by palm plantation companies there. The journalist published an exposé in the NZ Sunday Star Times in August implicating NZ dairy giant Fonterra in rainforest destruction in Indonesia and Malaysia.

“Indonesia’s rainforests are being destroyed at one of the fastest rates in the world. New Zealand should be helping to protect the climate and Indonesia’s remaining forests should not be destroyed,” said Suzette Jackson.

Research also revealed that a quarter of the world’s production of Palm Kernel Expeller (PKE) animal feed, a product of the Indonesian and Malaysian palm oil industry, was imported into New Zealand in 2008 with the majority going to feed dairy cows. At the time about 95% of all NZ dairy farms were shareholders within Fonterra.

After helping to document rainforest destruction in Sumatra, home to critically endangered Orang-utans and Sumatran Tigers, Greenpeace started campaigning against further deforestation for new palm oil plantations.

Production of palm oil has a triple whammy for the environment: destroying rainforest habitat to make way for palm plantations, putting carbon into the atmosphere when trees are destroyed and fossil fuels are used to process and ship PKE to market, and driving the intensification of dairying in NZ which increases methane emissions from that sector.

Once Greenpeace had documented what was happening in Indonesia, it began to blockade ships importing PKE into NZ at a time when NZ was importing a third of the global production of PKE to meet soaring demand in the dairying sector. It also targeted Fonterra and urged the company to stop importing PKE from ‘cleared’ rainforest land.

In 2010 Fonterra even closed its Facebook page in the face of public outcry about PKE use in NZ after Greenpeace posed difficult questions for the company in an ad about milk from cows fed with PKE.

After almost a decade of pressure from Greenpeace, Fonterra said in 2016 it would clean up its use of PKE and commit to using only ‘responsible palm oil products’ throughout its global supply chains. This followed a move by NZ State-owned Enterprise Landcorp to completely phase-out its use of palm kernel expellant (PKE).

Then, in 2018, a Greenpeace investigation revealed that Fonterra’s main supplier of PKE – Wilmar – was linked to the mass destruction of rainforest in West Papua, a region of New Guinea ruled by Indonesia. Aerial photos taken by Greenpeace showed an area of rainforest twice the size of the city of Paris had been destroyed.

In part prompted by the campaign against PKE imports, Greenpeace also renewed its earlier call for New Zealand to adopt ecological or “regenerative” agriculture as a positive alternative to the carbon emissions and freshwater pollution caused by conventional agriculture and dairying.

Freshwater and Big Irrigation

After 2007, Greenpeace expanded its Agriculture Campaign activities to include targeting freshwater pollution from dairying and nitrous oxide emissions resulting from synthetic fertiliser use, as well as big irrigation schemes and dams that encouraged the expansion of dairying at the expense of wild rivers and aquifers.

In 2016, Greenpeace launched an ambitious new campaign to change New Zealand’s polluting industrial model of dairy farming into a sustainable, regenerative model of farming that looks after our land, water, biodiversity, and people. The new campaign was led by new Greenpeace Agriculture Campaigner Genevieve Toop, who had previously been Greenpeace New Zealand’s Engagement Coordinator.

Greenpeace targeted the proposed big Ruataniwha dam scheme in Hawke’s Bay, which was the biggest at the time, and earmarked to be built on publicly-owned conservation land.

“This huge, costly irrigation plan will industrialise our farms, probably bankrupt more New Zealand farmers, and increase pollution into our rivers,” said Agriculture Campaigner Genevieve Toop. “And, if it goes ahead, it will hoover up hundreds of millions of dollars of taxpayers’ and ratepayers’ money.”

In 2016, Greenpeace successfully campaigned with locals to demand the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council withhold the $80 million of ratepayer funds that it had set aside to subsidise the dam.

In May 2016 Greenpeace blockaded the entrance to ACC’s multi-storey building in the middle of Wellington with six tonnes of dairy sewage in eight secure heavy-duty tanks, in protest at the Government department’s link to the controversial Ruataniwha irrigation scheme.

Then in June 2016 Greenpeace launched a legal challenge against the RMA resource consents granted by the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council to extend the area of land that could be irrigated by the proposed Ruataniwha dam scheme, which was now tipped to cost close to $1 billion to build.

“The public are being asked to fork out hundreds of millions of dollars on a dam that will cause more industrial dairy farming and more pollution of our rivers,” said Greenpeace Agriculture Campaigner Gen Toop. “It’s just wrong that the public, who will lose out on clean rivers thanks to the dam, have been shut out of this process.”

In September 2016, Greenpeace uplifted the site office of the proposed Ruataniwha dam and delivered it to the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council offices in Napier 100km away.

It was a classic ‘return-to-sender’ action according to Greenpeace Actions Coordinator Rob Taylor, who arranged the audacious action. It was also timed to coincide with voting papers landing in people’s letterboxes for upcoming local elections. Over 70,000 people also sent emails to the region’s councillors urging them to halt the scheme.

“After the recent gastro outbreak in Havelock North, the council needs to put people’s health before more industrial dairying and drop the Ruataniwha Dam,” said Greenpeace Agriculture Campaigner Genevieve Toop. “Local waterways in Hawke’s Bay are already polluted and under pressure. The dam will compound these problems by driving more intensive dairy farming.”

In October 2016 Greenpeace welcomed the preliminary results of the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council election, saying the new council’s top priority must be to ditch the Ruataniwha dam.

“The result shows Hawke’s Bay residents have had enough of contaminated waterways and don’t want more industrial dairy farming,” said Greenpeace Campaigner Mike Smith (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu). “We look forward to the new council swiftly exercising its power to stop the dam.”

Then in July 2017, after a sustained public campaign of opposition, the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council dropped the Ruataniwha irrigation dam scheme. That decision, as well as a Supreme Court ruling that the dam couldn’t be built on conservation land, stopped the dam being built.

“The Ruataniwha Dam was the poster child of the Government’s Think-Big irrigation agenda, which is now very clearly flailing and needs to be put down,” said Greenpeace Agriculture Campaigner Genevieve Toop.

In the wake of the Ruataniwha announcement, Greenpeace issued a warning to other think-big irrigation schemes, and demanded the Government’s irrigation subsidies be spent on a transition fund to more sustainable forms of farming or regenerative farming.

Greenpeace continued to target big irrigation projects with a series of actions in 2017 and 2018 aimed at halting the intensification of dairying and promoting regenerative agriculture as a positive alternative.

In February 2017, Greenpeace released a new video explaining the science behind river pollution that outlined the important link between irrigation schemes and river pollution:

“It’s a simple message,” said Greenpeace Sustainable Agriculture Campaigner Gen Toop, “more irrigation equals more cows. More cows mean more pollution.”

In June 2017, Greenpeace released a hard hitting report called Sick of too Many Cows detailing how intensive livestock farming could be endangering our health

In July 2018, Greenpeace fought hard against a planned mega dairy farm in the fragile tussock landscape of the Mackenzie Basin. A team of 45 activists locked themselves onto diggers and trucks to disrupt the construction of a large irrigation pipeline and unfurled a giant banner that read, ‘Stop Dairy Expansion’. The site was in a fragile landscape that is home to the endangered endemic Kakī/Black Stilt, the world’s rarest wading bird species with only 100 individual birds left.

“For the sake of the Mackenzie and our rivers, industrial dairy expansion has to stop,” said Greenpeace Sustainable Agriculture Campaigner Gen Toop. “Greenpeace isn’t against farming, it’s against bad farming, which this is a clear example of. This new mega-farm is a shameful example of how the rules there to protect our rivers and our environment from industrial dairying are failing.”

Shortly after Greenpeace’s action, even dairy giant Fonterra said it would, “prefer not to see more dairy expansion in the Mackenzie Basin”.

After a prolonged period of campaigning against John Key’s National-led Government and various regional councils that were promoting and subsidising big irrigation projects during the 2010s, Greenpeace s쳮ded in persuading the incoming new Government to stop funding big irrigation schemes.

Jacinda Ardern’s Labour-led Coalition Government scrapped the irrigation fund that had been set up by the previous government – Crown Irrigation Investments Ltd – in April 2018.

“This is a huge win for our rivers and all the New Zealanders who’ve worked long and hard to protect them,” said Greenpeace Sustainable Agriculture Campaigner Gen Toop. “Countless rivers have been saved from further destruction today, the Ruamāhanga, the Waitaki, the Hurunui to name just a few.”

Regenerative farming

Greenpeace’s short documentary film showcasing regenerative farming in New Zealand – ‘The Regenerators’ – featured at a UN conference in New York in November 2018. Shortly after that, Greenpeace called on the NZ Government to ban synthetic fertilisers because of the nitrous oxide emissions that result from its use and which destroy the climate.

In August 2019 Greenpeace called for the halving of the NZ dairy herd after a NZ Government report identified dairying as NZ’s dirtiest industry, and a UN IPCC report said there was an urgent need to revamp global food systems away from industrial meat and dairy production.

Shortly after that in September 2019, the NZ Government proposed a cap on synthetic fertiliser use to “help rivers”. It was a major step in reducing carbon emissions and water pollution from the agriculture sector that was welcomed by Greenpeace Campaigner Gen Toop.

Following the establishment of the Government’s new $1 billion Provincial Growth Fund in 2018, some – albeit far smaller – support was given to irrigation while the NZ First Party’s Shane Jones was the relevant minister.

Greenpeace and others including Forest and Bird and Fish & Game continued to campaign against government handouts to big irrigation schemes. In May 2020, Greenpeace called for the Government to establish a new $1 billion regenerative agriculture fund to help create a just transition to a truly ecological form of agriculture in New Zealand, as well as the fast-tracking of public funding for farm waterway fencing and plantings with Government finance.

Greenpeace also continued its campaign for a ban on synthetic Nitrogen fertiliser by blockading the Ballance factory in Taranaki in July 2020.

In October 2019 Greenpeace criticised the Government’s decision to exclude farming from the Emissions Trading Scheme describing it as a “major sell-out”.

In March 2020 Greenpeace proposed that the Government fund a Green New Deal recovery package in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. He said that the Covid-19 public health crisis presented a unique opportunity to build a greener, healthier, and more resilient economy that puts people and the planet first.

The challenge now is to ensure that no new public funding is handed out to big irrigation schemes, to get synthetic Nitrogen fertiliser banned, and to persuade the Government to shift its support into funding regenerative farming.

If the Government does this, says Greenpeace, the country will be better able to respond to the climate, biodiversity, and inequality crises that it now faces.