Climate and oil

Putting climate change ‘on the map’

Greenpeace’s Climate Campaign started in New Zealand in 1990 at a time when there was growing public awareness of the damage being done to the climate by fossil fuels, and to the planet’s protective ozone layer by CFC chemicals.

New Zealand was seen as an important country in the climate change debate because of the relatively high level of existing renewable energy in the 1980s when climate change first emerged as an environmental issue, which meant NZ could be a positive example of an OECD country with about 70% of its energy coming from renewable sources, and a realistic expectation that it could achieve 100% renewables in the near future because it had good wind, sun, geothermal, and tidal energy resources. There was also the potential for significant energy efficiency savings to avoid the need for building new fossil-fuelled power stations.

The scale of society also meant positive change was more possible to envisage here compared to bigger continent-sized countries with huge populations such as the USA and the USSR/Russia. The advent of MMP also meant there was an electoral system theoretically more amenable to public pressure on environmental issues than the old ‘first past the post’ system that dated from the British Empire era.

The position of Greenpeace in New Zealand society following the Rainbow Warrior bombing also meant that it had more cut-through than Greenpeace did in some larger countries, and relatively good access to decision-makers.

No new fossil-fuelled power stations

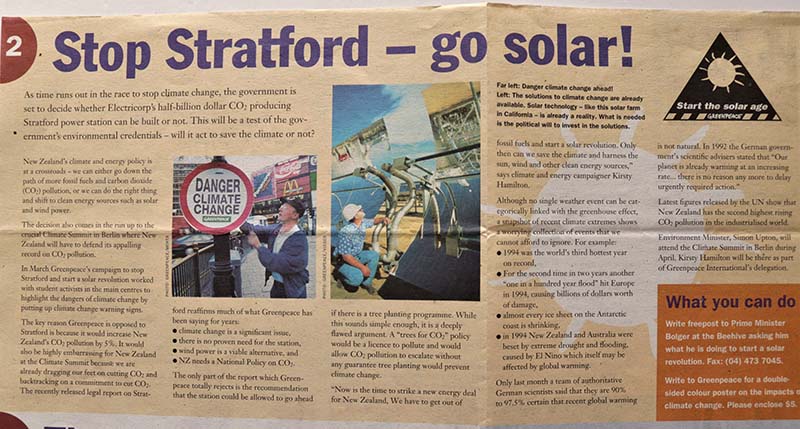

The Climate Campaign began in New Zealand with a focus on opposing new fossil-fuelled power station proposals and the ineffective voluntary tree planting policy of successive National Governments, and using the new RMA as a process through which to raise the impact on the climate of burning more fossil fuels.

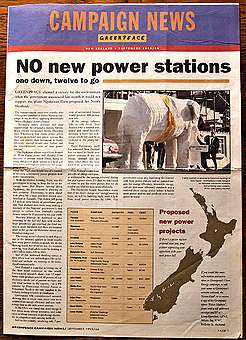

Proposals for new fossil-fuelled power stations at Stratford, Southdown, Otahuhu and Te Rapa in the 1990s gave Greenpeace concrete targets to oppose, that were also platforms to publicly raise climate change, energy efficiency, and renewable energy issues.

It was also important to establish the need for more effective climate action by communicating the potential impacts of climate change. Greenpeace campaigned publicly on this point and worked to educate politicians and decision-makers about the impacts of climate change, especially in New Zealand, Antarctica, and the wider Pacific region.

In the early 1990s Greenpeace also campaigned for greater protection of the planet’s protective ozone layer and swift implementation of the 1989 Montreal Protocol. In June 1992 a Greenpeace team of climbers scaled Parliament to attach a giant pair of inflatable sunglasses on top of Parliament Buildings while Greenpeace New Zealand’s first Climate Campaigner, Kirsty Hamilton, delivered a petition with 18,000 signatures and 2,000 letters urging the Government to move faster to rapidly phase-out ozone-depleting chlorinated CFC and HCFC chemicals.

The NZ Government eventually legislated to phase-out CFCs and HCFCs under the Ozone Layer Protection Act, which passed in 1996.

‘Say No to Stratford’

State-owned Enterprise Electricorp’s Stratford power station was the first of the big new fossil-fuelled power station proposals of the period, making it an important campaign target for Greenpeace.

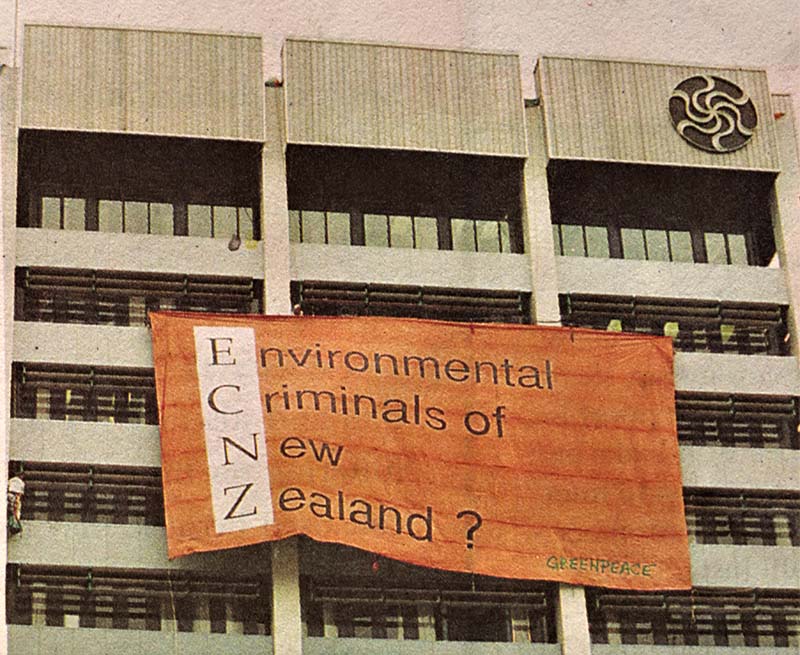

Greenpeace launched its campaign against the proposed Stratford power station in 1993 by hanging a giant banner off the Electricorp head office in Wellington that read, ‘Environmental Criminals of New Zealand E.C.N.Z.’

In 1994 Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Kirsty Hamilton wrote to the Minister for the Environment to urge them to ‘Call-in’ the application for resource consents. She and Greenpeace Legal Counsel Duncan Currie participated in the subsequent Resource Management Act (RMA) process and public hearings that the minister initiated. After that ran its course, the Board of Inquiry and Environment Minister Simon Upton approved resource consents for the power station in 1995, combined with a weak and ineffective ‘tree planting’ carbon offsetting policy that was subsequently seen to fail.

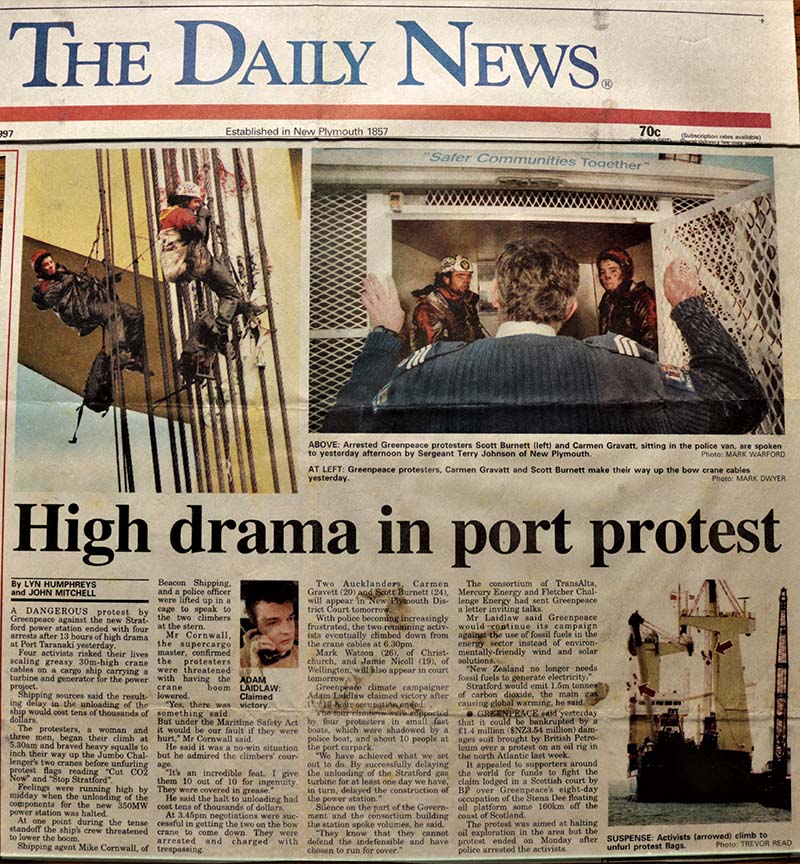

Greenpeace continued to target its construction, working with local activists in Taranaki and using nonviolent direct action tactics to sound the alarm on the destructive impacts that its carbon emissions would have on the climate. Building the 400-megawatt power station was set to increase NZ’s carbon dioxide emissions by about 6% or 1.5 million tonnes a year.

This culminated in August 1997 with a team of four Greenpeace activists – Carman Gravatt (20), Scott Burnett (24), Jamie Nicholl (19), and Mark Watson (26) – boarding the cargo ship carrying the turbine generators for the power station into Port Taranaki. By climbing up the heavy greased cables and locking onto the ship to stop the unloading of the generators they s쳮ded both in delaying the unloading and making the power station once again into a high-profile public issue.

Greenpeace also opposed new power station proposals at Southdown, Otahuhu, and Te Rapa through the Resource Management Act (RMA). Climate Campaigner Adam Laidlaw and Legal Counsel Duncan Currie made submissions and attended resource consent hearings but in the end consents for all three were approved by the relevant consenting councils in Auckland and Waikato. Greenpeace appealed the consents on climate change grounds and s쳮ded in negotiating reductions in their size and therefore emissions through the appeals processes.

Shell and the judicial murder of Ken Saro-Wiwa

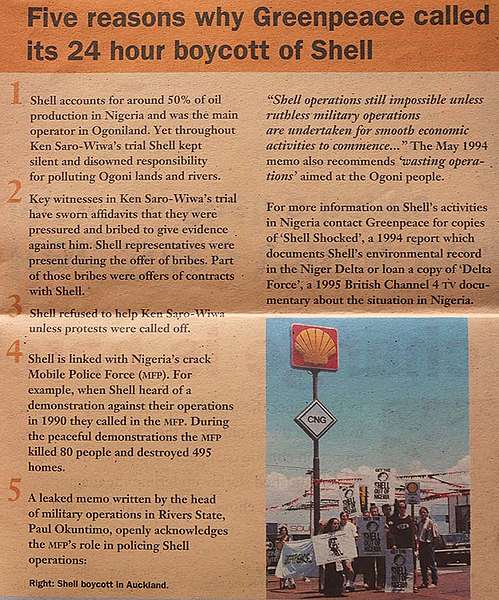

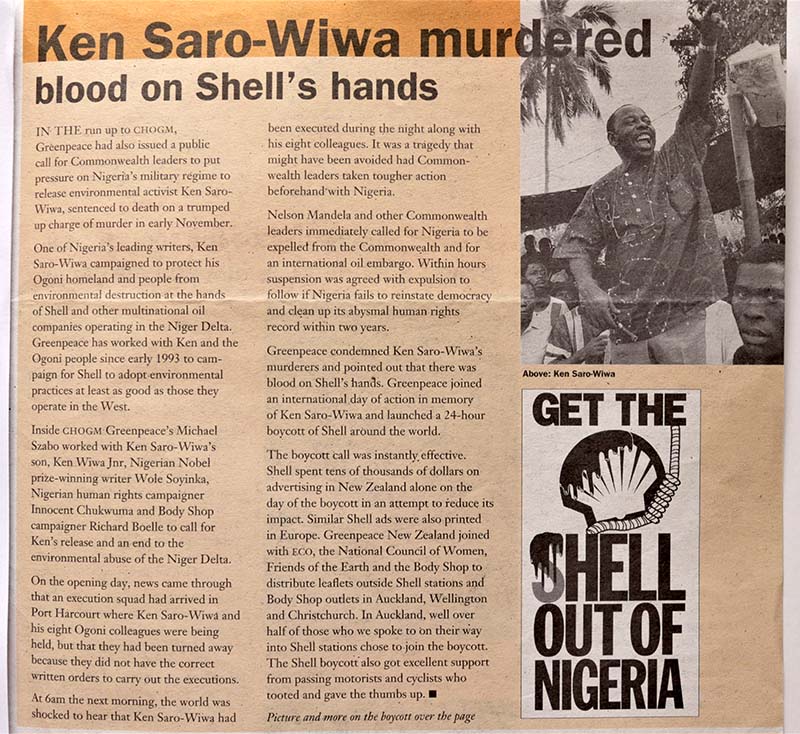

One of the two big issues that dominated the November 1995 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Auckland was the impending planned execution of the environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa by the military regime that ruled Nigeria.

Ken Saro-Wiwa was Ogoni, an ethnic group in Nigeria whose homeland, Ogoniland, in the Niger Delta, had been targeted for oil extraction since the 1950s and which had suffered extreme environmental degradation from decades of oil waste being dumped into the delta.

Initially as spokesperson and then as President of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) he had led a non-violent campaign against the environmental damage being done to the land and waters of Ogoniland by the operations of the multinational oil industry, especially the Royal Dutch Shell company, known just as ‘Shell’ from its service stations in NZ.

He was also an outspoken critic of the Nigerian Government, which he viewed as reluctant to enforce environmental regulations on the big multinational oil companies operating in the Niger Delta. At the peak of MOSOP’s non-violent campaign, Ken Saro-Wiwa was arrested and tried by a Nigerian military tribunal for allegedly masterminding the murder of Ogoni chiefs at a pro-government meeting.

The military regime ruled by Sani Abacha arrested Ken Saro Wiwa and eight of his fellow Ogoni MOSOP supporters on trumped-up charges following widespread Ogoni protests against Shell Oil’s devastating operations in the Niger Delta.

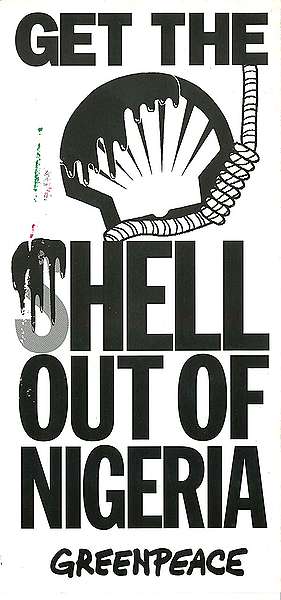

Inside the CHOGM venue, Greenpeace New Zealand Campaign Manager Michael Szabo met and encouraged delegations to condemn the Nigerian military regime’s planned execution of Ken Saro Wiwa and the eight other MOSOP supporters. Greenpeace also publicly demanded that Shell use its influence with the Abacha regime to stop it from carrying out the executions, but Shell remained silent.

When it came, Greenpeace welcomed the CHOGM’s decision to suspend Nigeria from the Commonwealth and to impose an international arms embargo on the Abacha regime, which had seized power in a military coup. Shell remained conspicuously silent on the issue throughout the meeting.

Then news emerged in New Zealand during the early hours of 11 November that Ken Saro-Wiwa had been executed in Nigeria. It reportedly took five attempts to execute him by hanging and his last words were reported to be: “Lord take my soul, but the struggle continues.”

Greenpeace immediately expressed outrage at the judicial execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his eight Ogoni compatriots, and at Shell for its complicity in the Abacha regime’s actions in the Ogoni Delta.

Greenpeace Campaign Manager Michael Szabo met with Ken Saro-Wiwa Jnr in Auckland that morning, shortly after the news of the execution reached NZ. “Ken Saro-Wiwa Jnr was incredibly composed and dignified despite having just received the tragic news of his father’s brutal execution,” recalls Michael Szabo. “I watched as he gave incredibly powerful interviews refuting the Abacha regime’s false claims about his father and describing Shell’s environmental devastation of the Niger Delta.”

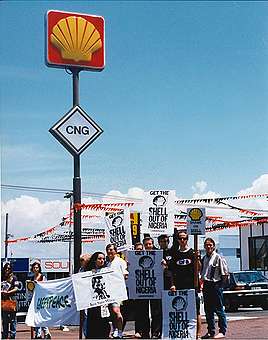

Greenpeace called a 24-hour boycott of Shell service stations around New Zealand for the following weekend. Greenpeace joined with ECO, National Council of Women, Friends of the Earth NZ, Trade Aid, and the Body Shop to organise protests with placards that read “GET THE SHELL OUT OF NIGERIA” and to hand-out campaign leaflets at Shell service stations in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. Well over half of the people arriving at those service stations joined the boycott and there was a high level of support from passing motorists and cyclists tooting and giving a thumbs-up.

Over a decade later on 9 June 2009, Shell agreed to pay US$15.5 million in settlement of a legal action in which it was accused of collaborating in the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the eight other MOSOP supporters. The settlement was reached on the eve of the trial in a US federal court in New York, and was one of the largest payouts agreed by a multinational corporation charged with human rights violations.

Then, in April 2019, it emerged at hearings of the International Criminal Court in The Hague that Shell had in fact bribed individuals to lie in the Nigerian court case that framed Ken Saro Wiwa and the other eight MOSOP supporters for a murder they did not commit.

This meant that all nine of them had been hanged on the basis of false testimony that Shell had paid for. Shell had remained silent at the time of the CHOGM in Auckland and of the executions, despite the knowledge that the convictions were based on false testimony that the company had bribed witnesses to fabricate.

Stopping Meremere

The next new power station proposal that came forward was for a $223 million ‘co-generation’ waste incineration scheme at the mothballed Meremere power station south of Auckland, which was made by the Olivine company in 1997. The company proposed to burn large quantities of household solid waste that it would truck in from Auckland and the Waikato to generate electricity, using coal as the ‘feeder fuel’.

Greenpeace joined with Friends of the Earth NZ, North Waikato Environmental Group, River Watch, the Recycling Organisation of NZ, local farmers, and local residents to oppose it on the grounds that it would produce huge quantities of highly toxic emissions containing cancer-causing dioxins and huge carbon emissions.

“By stopping the proposed waste incineration scheme from burning a million tonnes of municipal solid waste per year, we stopped a huge new source of toxic dioxin emissions from firing up. If it had gone ahead it would also have created huge carbon emissions from burning coal as its feeder fuel, and burning a vast amount of plastic, wood, cardboard, and paper that could instead have been re-used or recycled,” recalls Michael Szabo, who was Greenpeace’s Toxics Campaigner who ran the campaign with Climate Campaigner Adam Laidlaw.

The proposal, which was also opposed by Tainui Corporation, Huakina Development Trust, Ministry for the Environment, Auckland Regional Council, Manukau City Council, and Waitakere City Council, was defeated in 1999 when Waikato Regional Council decided not to issue the required RMA resource consents for it to operate.

Brilliant Solutions

The promotion of solar energy was also a growing part of Greenpeace’s climate campaign at that time. The early work on this included Greenpeace’s ‘Solar Pioneers’ project initiated by Climate Campaigner Adam Laidlaw in 1997-98, which recruited thousands of members to commit to installing solar hot water systems on their houses by the year 2000 to help kick start the NZ solar market.

This was followed by publication of the ‘Brilliant Solutions’ report in 1998 setting out a vision for solarisation in New Zealand, and the building of Greenpeace’s mobile Solar Café which toured the country in 1998 with SV Rainbow Warrior II to demonstrate to the public and politicians that solar was a viable technology to generate electricity for powering homes and offices.

Greenpeace New Zealand also set up its first website to coincide with SV Rainbow Warrior II’s tour in 1998 which included touring the new Solar Café.

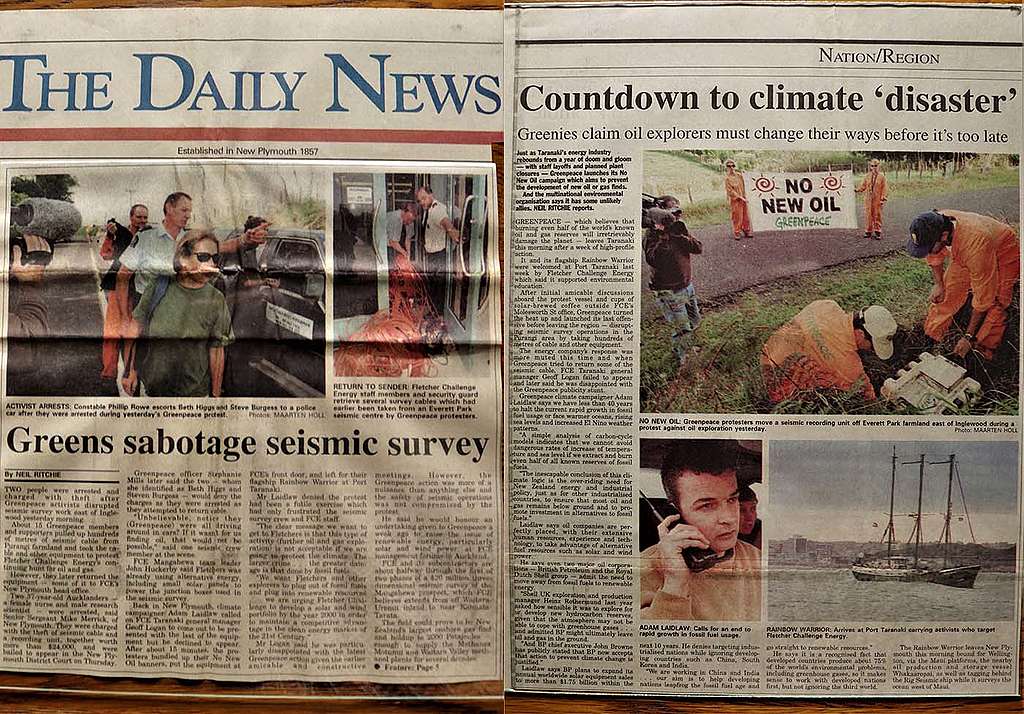

No New Oil

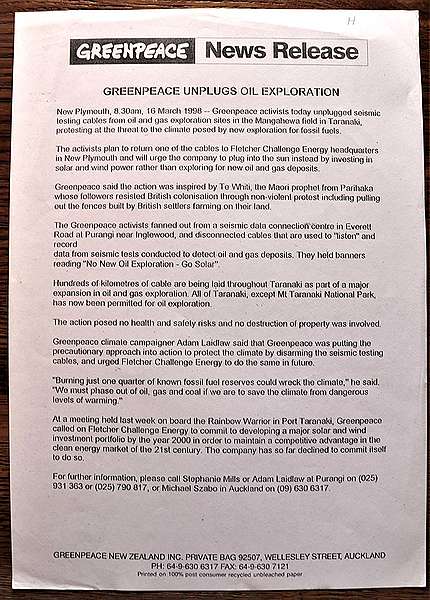

During SV Rainbow Warrior II’s tour of New Zealand in March 1998 multiple teams of Greenpeace activists unplugged Fletcher Challenge Energy’s seismic oil and gas testing cables to disrupt the company’s new oil exploration activities in Taranaki. Actions Coordinator Rob Taylor delivered one of the giant cables and its data collecting equipment to Fletcher Challenge Energy’s HQ in New Plymouth.

Greenpeace publicly urged the company to instead plug into the sun by investing in solar and wind power, and said that the action was inspired by Te Whiti, the Māori leader from Parihaka whose followers resisted colonisation in the 1800s through non-violent protest, including pulling out the fences built by British settlers farming on stolen Māori land.

Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Adam Laidlaw warned that hundreds of kilometres of cable were being laid in Taranaki as part of a major expansion in oil and gas exploration there, and that the whole of the Taranaki region except Mt Taranaki National Park had recently been designated for new oil exploration by the Government. At sea, SV Rainbow Warrior II towed a giant inflatable oil barrel with the words ‘No New Oil’ painted on it, out to the oil field off the Taranaki coast.

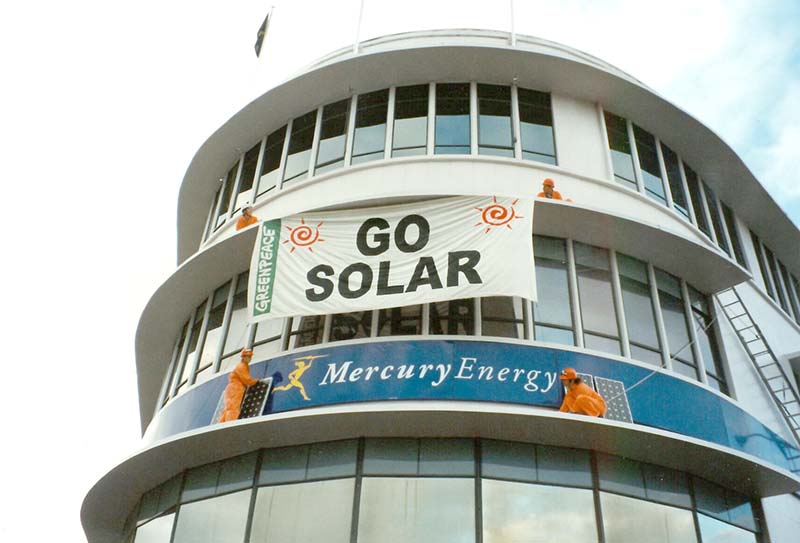

Greenpeace also incorporated solar panels into direct actions targeting Mercury Energy’s head office during the Auckland power crisis in 1998 and Parliament in 1997 when Greenpeace urged the Government to ‘Go Solar’ and for a solar power system to be installed on the Parliament Buildings.

Greenpeace plugs into the sun

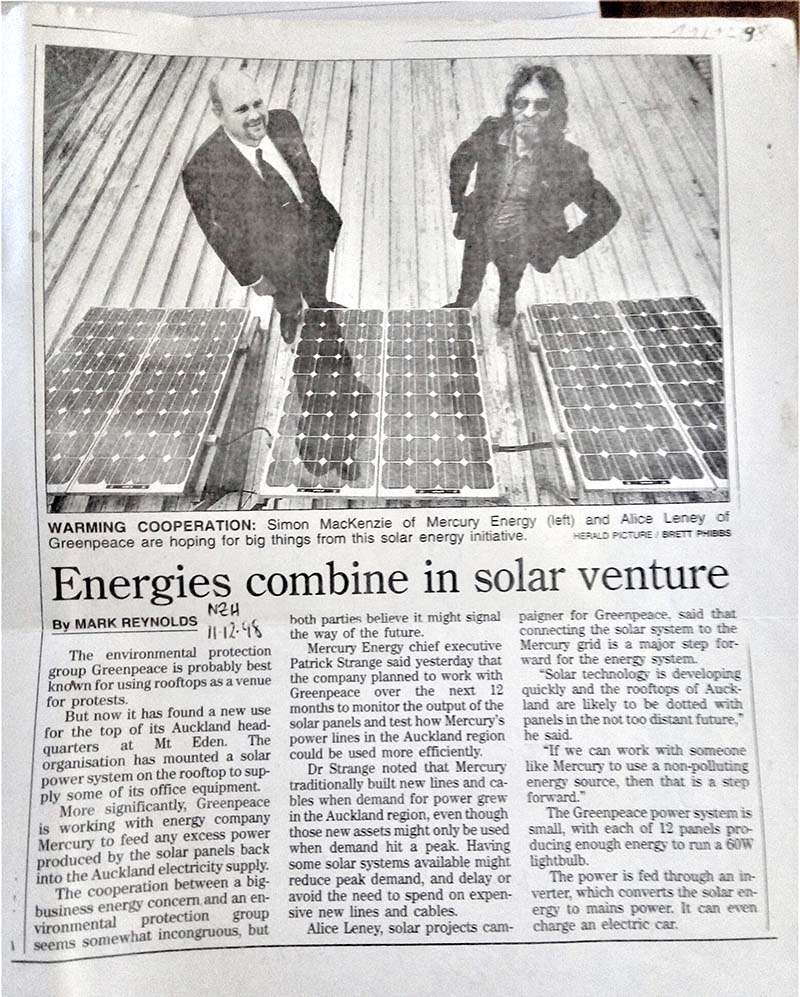

After touring the Solar Café, its solar panels were installed onto the roof of the Greenpeace office in Auckland and a net-metering system developed by Greenpeace solar technologist Alice Leney. In subsequent years the Greenpeace Educational Trust funded the modernisation and expansion of the rooftop solar system and electricity was able to be sold into the national grid through an agreement that Alice Leney negotiated for Greenpeace with Mercury Energy.

‘Keep the coal in the hole’

In the early 2000s, Greenpeace began campaigning against coal mine expansions, proposals for new coal mines, and coal imports from Indonesia that were destined to be burned in Genesis Energy’s Huntly power station. Once again, as with the earlier power station proposals, these coal actions gave Greenpeace a platform to make climate change a more ‘concrete’ issue that the public could grasp.

Stopping ‘Marsden B’

Another fossil-fuelled power station proposal appeared in 2004 in the form of the Mighty River Power Company’s ‘Marsden B’. Greenpeace joined with local residents, iwi, and other environmental groups to oppose the company’s application for the new coal-fired power station near Whangarei. This was a strategic campaign because there were also other fossil fuelled power station proposals at the time, recalls Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Vanessa Atkinson.

The Marsden B campaign included mass protest and a marathon nine-day rooftop occupation of the building in February 2005 that started on the day that the Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change entered into force.

Greenpeace activists scaled the 50-metre high building which housed an old moth-balled oil-burning power station, which was to be the site of the proposed new coal-fired power station near Whangarei. They occupied the roof and unfurled a giant yellow banner that read “SAVE THE CLIMATE, STOP COAL” and featured the image of a burning globe.

“State-owned generator Mighty River Power had plans to refurbish the relic as a coal burning generator,” recalls Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Steve Abel, “As the first coal power station built in 22 years (since Huntly) we felt it was vital to not allow the precedent to be set that new coal was ok in the era of climate change.”

Greenpeace’s Climate Campaign was able to pivot its anti-coal campaigning capacity into the Marsden B campaign. It was also timely because the proposal came at a moment when climate change policy decisions were being made by the NZ Government, and it gave Greenpeace a platform to further pursue the inclusion of climate change in the Resource Management Act (RMA) through work done by Campaign Manager Cindy Baxter and Legal Counsel Duncan Currie.

“I bumped into Mighty River Power CEO Doug Heffernan some years later at The Bridgeway Cinema in Northcote and he said, ‘That Marsden B decision changed the course of our new energy investment and gave us a heavier focus on geothermal’,” recalls Steve Abel. “So, in effect, he confirmed that our strategy was correct. The ultimate goal is culture change, to make a specific definition of environmentalism the norm. Platform issue fights like Marsden B are a pathway to tangibly achieving and communicating system change.”

Clean Energy Guide

Following the success of Greenpeace’s ‘GE-Free Food’ consumer guides in persuading supermarkets and food companies to adopt GE-Free policies in the early 2000s, the Climate Campaign produced a series of ‘Clean Energy Guides’ ranking electricity companies according to their current and future impact on the climate in the period 2005-2007. Having a way to engage with the public on climate and energy issues became an increasingly important part of Greenpeace’s campaign toolbox, offering a way to engage with people and harness their collective purchasing power.

Mighty River Power scrapped its Marsden B proposal in March 2007, which would have been the first major coal-fired power station built in New Zealand for over 30 years.

“This is a great win firstly for the climate and for the thousands of Kiwis who opposed Marsden B. Mighty River Power’s decision is another nail in the coffin for coal – New Zealand’s energy future is in renewable energy not fossil fuels,” said Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Vanessa Atkinson.

Greenpeace continued to oppose the mining and burning of coal to generate electricity. In November 2009 Greenpeace activists shut down a pit at a Southland lignite coal mine used by dairy giant Fonterra to help fuel operations at its Edendale dairy factory.

New Zealand Energy Revolution

Shortly after the ‘Marsden B’ proposal was defeated, Greenpeace targeted the Huntly coal-fired power station and released a new report – New Zealand Energy Revolution – setting out how NZ could switch to 100% renewable electricity by 2025.

SV Rainbow Warrior II toured New Zealand again in March-April 2008 to campaign for more renewable energy generation to tackle the threat of climate change. During the tour, SV Rainbow Warrior II and her crew blocked a shipment of 60,000 tonnes of coal being exported by state-owned coal miner Solid Energy from the port of Lyttelton.

Then Helen Clark’s Labour-led Coalition Government’s Emissions Trading Scheme passed into law in September 2008, shortly before that year’s general election.

Climate Campaigner Vanessa Atkinson recalls, “When a National-led Coalition came into power at the end of 2008 they rode roughshod over public opinion and gave Greenpeace a big target to campaign against on climate change. That meant Greenpeace was able to shift and expand the climate campaign ‘playing field’ into mining on conservation land and new oil exploration at sea.”

“That meant there was a more ‘target rich’ environment of Greenpeace, but it was a double-edged sword because more opportunities also meant more battles to fight and a longer slog to change government policies.”

The ‘Sign-On’ campaign

With the change to a National-led Coalition Government led by John Key, a group of high-profile Kiwis joined with Greenpeace in 2009 to launch the new ‘Sign On’ campaign and called for strong climate action.

The campaign aimed to generate an unprecedented level of support for John Key’s Government to sign on to an emissions reduction target at the UN climate talks in Copenhagen in December that year of 40% by 2020.

By the time of the talks in December 2009 the online campaign had received the support of over 230,000 people. Despite all the support, the NZ Government’s position still fell far short of the target at the talks.

Then, as if adding insult to injury, John Key’s National-led Coalition Government gutted the Emissions Trading Scheme, sending a clear message to the international community that New Zealand was not serious about tackling climate change.

40,000 march against mining on Schedule 4 conservation land

The same National-led Coalition Government also proposed to allow mining on Schedule 4 public conservation land. That led Greenpeace to work with environmental allies and its supporters to oppose and then stop the Government’s plans, culminating in an historic march of 40,000 people up Queen Street in Auckland on 1 May 2010. In the face of such a powerful demonstration of public opposition to its plans, the Government soon backed down.

“When the Government announced its plans for mining on conservation land, Steve Abel read the room well on it, and Greenpeace called the 1 May 2010 march against those plans in collaboration with the other environment and conservation groups. We had two weeks to organise for it which was a huge amount of work. The Key Government was arrogant and they also overplayed their hand on that,” recalls Chris Hay, who was Greenpeace’s Actions Coordinator at the time.

“Steve Abel is a master of marches and played an instrumental role in uniting New Zealanders. The 40,000 strong anti-mining march in Auckland on 1 May 2010 was a phenomenal show of New Zealanders’ love of nature,” comments Carmen Gravatt, who was Greenpeace New Zealand’s Campaign Director at the time.

During the 2010s Greenpeace continued to help mobilise large numbers of people through inspiring direct action protests and public rallies outside oil conferences and oil company head offices. These activities also gave people the information and tools to switch energy providers, and included online petitions that gathered many tens of thousands of signatures.

Te Whānau-ā-Apanui’s call to ‘Stop Deep Sea Oil’

In 2011, Greenpeace and a ‘Stop Deep Sea Oil’ Flotilla of independent sailors responded to a call by Te Whānau-ā-Apanui to join them in their resistance against Brazilian oil giant, Petrobras, which was due to begin seismic blasting in the deep waters of the Raukumara Basin in search of new oil.

Stop Deep Sea Oil’ flotilla send off from Auckland with speeches including Steve Abel and the crowd singing

Over 42 days the Flotilla boats (SV Windborne, SV Secret Affair, SV Siome, SV Tiama, SV Vega) and the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui-owned San Pietro disrupted the giant seismic blasting ship’s search for oil, despite the deployment of the NZ Navy and NZ Police, and with the latter boarding some of the boats to make arrests.

During that time, activist Kylie Matthews (Ngāpuhi), dived into the sea in front of the giant seismic blasting ship with a ‘Stop Deep Sea Oil’ banner, forcing it to change course.

Rikirangi Gage, Elvis Teddy, and San Pietro

A few days later, Te Whānau-ā-Apanui leader Rikirangi Gage was on board San Pietro alongside Apanui fisherman, Elvis Teddy, when Gage told the oncoming seismic ship over the radio that, “we will not be moving, we will be doing some fishing”.

The protests s쳮ded in cutting short the seismic survey ship’s work there and the following year Petrobras handed in their oil exploration permit and announced their exit from NZ.

“The Raukumara basin campaign involved a David and Goliath confrontation with the problem: the Flotilla of small boats out there with a huge seismic survey ship, bearing witness,” recalls Climate Campaigner SteveAbel. “The ‘alliance’ with te Whānau-ā-Apanui was brilliant and inspired. Once Mike Smith and Hinekaa Mako were on the team we were able to form the relationship with the local iwi and our alliance.”

Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Vanessa Atkinson was also on the water watching events unfold that day: “During the campaign against Petrobras in the Raukumara Basin I was the campaigner on SV Windborne and later SV Infinity in the ‘Stop Deep Sea Oil’ Flotilla’. We’d been following the Petrobras seismic testing ship and then our Greenpeace team did an action putting swimmers in the water in front of the survey ship to disrupt the surveying. The Navy had been deployed there and the Air Force Orions were buzzing us, so it felt like ‘it was all on’.”

“Then te Whānau-ā-Apanui kaumatua Rikirangi Gage and Elvis Teddy came in on San Pietro and did their thing. I have this memory of a tiny fishing boat on the water and Rikirangi Gage hailing the survey ship on the radio.”

“He gave this amazing speech, speaking for his ancestors and his people, and about their sovereignty over those waters. Then he said, ‘We will not be moving. We will be doing some fishing’. That sent chills up my spine. It was amazing and it was a privilege to be there with them.”

#SaveTheArctic

In February 2012 actor Lucy Lawless and six Greenpeace activists boarded and occupied a Shell-contracted drillship, stopping it from departing the Port of Taranaki for the remote Arctic. MV Noble Discoverer was due to depart on a 6,000 nautical mile journey to drill three exploratory oil wells in the Chukchi Sea off the coast of Alaska.

Lucy Lawless, famous for her roles in Xena: Warrior Princess and Spartacus, and the six activists boarded the vessel, scaling its 53-metre drilling derrick where they hung banners that read, “Stop Shell” and “#SaveTheArctic.”

“I’m here today acting on behalf of the planet and my children,” said Lucy Lawless. “Deep-sea oil drilling is bad enough, but venturing into the Arctic, one of the most magical places on the planet, is going too far. I don’t want my kids to grow up in a world without these extraordinary places intact or where we ruin the habitat of Polar Bears for the last drops of oil.”

The occupation ended on its fourth day after police climbed the ship’s drilling tower to Lucy Lawless and the other six activists. Despite the fact that the charge of “unlawfully being on a ship” was available, local prosecutors chose to charge the protestors with the more serious crime of burglary. Greenpeace insisted that no property was taken or damaged during the occupation.

A year later Greenpeace welcomed news that Shell had ditched its plans to drill in the Arctic in 2013.

“Shell’s multi-billion dollar Arctic investment lies in tatters today, and so does the company’s reputation. They massively underestimated the challenges posed by drilling off Alaska, and pushed on regardless, determined to spark a new Arctic oil rush,” said Greenpeace Executive Director Bunny McDiarmid.

“The huge global movement that sprang up to oppose them started right here in New Zealand, when a small group of volunteers boarded a Shell-contracted drilling ship in Taranaki, to try and stop it heading for the Arctic. Shell have dropped plans to drill this year, but when they try to head to the Arctic again, the millions of people who have backed the campaign to make this beautiful and special place off-limits for oil drilling will be waiting for them.”

A few weeks later in February 2013 Lucy Lawless and the six other activists were convicted and sentenced to 120 hours community service each for attempting to stop the Arctic-bound drillship MV Noble Discoverer departing from New Plymouth.

Speaking outside Taranaki District Court, Lucy Lawless said, “We are proud to have taken part in our attempt to stop Shell’s reckless plans to drill for oil in the pristine Arctic. Since we occupied the Noble Discoverer, it has become evident to everyone watching, from the millions who have signed Greenpeace petitions to the US Government now examining Shell’s plans, that it can never be safe to drill in the Arctic.”

“Shell’s Arctic programme has cost them billions and it’s now regarded as an eye-wateringly expensive failure. Let’s embrace clean energy; we’re going to have to anyway, so why not do it before they cause a major oil spill in the Arctic, and consign our grandchildren to an uncertain and dangerous world?”

SV Vega and the ‘Oil-Free Seas Flotilla’

The next big oil company that Greenpeace and the ‘Stop Deep Sea Oil’ Flotilla went up against was Texan oil driller Anadarko, which came to NZ to carry out seismic blasting off Kaikoura and to drill for oil in deep water directly off the Raglan coast.

Greenpeace Executive Director Bunny McDiarmid along with Henk Haazen and former Green Party Co-leader Jeanette Fitzsimons sailed out as part of a new six boat ‘Oil-Free Seas Flotilla’ to confront the huge Anadarko drilling ship off the Raglan coast in November 2013.

The three of them sailed SV Vega into the 500-metre exclusion zone to deliberately break the Key Government’s ‘Anadarko Amendment’, but they were not arrested by police.

At the height of the Flotilla’s protest against Anadarko, thousands of people also mobilised to paint banners and rally on West Coast beaches in solidarity with the Flotilla’s at-sea protest action.

“Jo McVeagh was Greenpeace’s Volunteer Coordinator. She used that role to help set up the Oil-Free network as a loose alliance. That also involved non-violent direct action training, banner making training, and the sharing of technical information and sometimes the loaning of our equipment, so the campaign spread and became viral, and success bred success,” explains Chris Hay, who was Actions Coordinator 2000-2013.

Anadarko pulls the plug

Anadarko pulled the plug on its NZ operations in March 2014 after an unsuccessful drilling campaign that was met with sustained opposition.

Greenpeace Campaigner Mike Smith (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) describes the history of the campaign, as follows: “I believe that the climate campaign and its subset issues have been, and will continue to be, fundamentally and critically important.”

“Fossil fuel and agricultural emissions make up over 40% of our total emissions, and in the face of an aggressive deep sea oil exploration regime it was crucial to prevent the oil industry from expanding its operations in our waters.”

“I was recruited into the oil campaign by te Whānau-ā-Apanui when the spectre of oil exploration appeared on their horizon and I was asked by them to assist with their campaign against Petrobras.”

“We thought that some capacity on the water would be useful and I approached Greenpeace Executive Director Bunny McDiarmid to seek the support of the Greenpeace Flotilla that had been active in the Nuclear-Free Pacific movement.”

“As Greenpeace already had its eye on the oil industry’s ambitions, they agreed to co-campaign together.”

“An important dynamic of that aspect of the campaign was that Greenpeace was engaging as an ally to te Whānau-ā-Apanui as opposed to the reverse. The nature of this arrangement was critical to its success. At that point I joined Greenpeace to assist the organisation to navigate the cultural landscape.”

“The campaign progressed over a couple of years with te Whānau-ā-Apanui tribal governance and Greenpeace alternating the organisation of various aspects of the campaign which ended successfully with the withdrawal of Petrobras and the surrender of their permits.”

“The oil exploration frontline then shifted to the East Coast of the South Island and Greenpeace supported the campaign there by enabling local community organisation and activism. This included sponsoring photo journalist John Wathan to tour the South Island giving his eye-witness account of the Anadarko/BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.”

“Once again, the local iwi played a crucial role in mandating and legitimising the local opposition to oil exploration which was instrumental in pressuring Anadarko to abandon their prospecting.”

Stopping Statoil

In September 2014 a thousand protesters marched up Queen Street in central Auckland as part of the Waiho Papa Moana Hikoi to the NZ Petroleum Summit in opposition to Norwegian oil giant Statoil.

The march was the final stage of a four-day protest that started in Cape Reinga. The Hikoi was joined by Oil-Free Auckland and Greenpeace supporters, including actress Lucy Lawless.

“We’ll do whatever’s necessary,” Hikoi organiser Mike Smith told 3 News. “We’re fighting quite hard against this and my advice [to Statoil] would be just don’t waste any money here; pull out before you’ve made any significant investment.”

Later that year, Greenpeace activists barricaded Norwegian oil giant Statoil’s new Wellington office to close it down. A total of 19,000 Greenpeace supporters also emailed the company urging it to stop its oil exploration activities and take its drill ships back to Norway.

In May 2015 a delegation of Te Parewhero kaumātua Te Wani Otene and Greenpeace Campaigner Mike Smith (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) met with representatives from the indigenous Saami Parliament in Norway – the Samedeggi – to discuss their opposition to Statoil exploring for new oil off the Northland coast.

In October 2016, Saami President Aili Keskitalo reciprocated by making a journey to New Zealand and the Far North to meet with local iwi and Mike Smith to discuss Statoil’s activities. On the day that Aili Keskitalo arrived, Statoil announced that it would not continue exploring off the Northland coast and instead relinquished its oil and gas permits in the Reinga Basin.

Greenpeace Campaigner Mike Smith (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu) describes the campaign in Northland as follows: “iwi in the north quickly declared opposition to the Norwegian oil company Statoil and the issue gained huge support amongst the Māori population, including a survey of 6,000 respondents indicating to the local Member of Parliament that 86% of his constituents opposed oil exploration in Northern waters.”

“The National iwi Chairs Forum declared its opposition to oil exploration and a delegation of Northland iwi Leaders travelled to Norway to meet and discuss our opposition with the indigenous Saami Parliament, the shareholders, and company officials of the state oil company Statoil.”

“Subsequently the President and senior officials of the Saami Parliament travelled to Aotearoa on a fact finding tour and on the day of their arrival, Statoil abandoned their plans in the region.”

‘The Crossing’

Greenpeace also continued to target new oil exploration in the Arctic. In April 2015, six Greenpeace activists including New Zealander Johno Smith boarded Shell Oil’s Polar Pioneer while it was en route across the Pacific to the Arctic, as part of Greenpeace’s global campaign to disrupt Shell’s attempts to drill for oil in the Arctic.

The month-long action – d믭 ‘The Crossing’ – was coordinated by Rob Taylor, Carmen Gravatt, and Nick Young of Greenpeace New Zealand. Five months later, in September 2015, Shell abandoned its multi-billion dollar oil drilling operations in the Alaskan Arctic empty-handed.

SV Rainbow Warrior III returned to tour NZ in 2015, including visiting the Subantarctic Islands, to continue the campaign against deep sea oil exploration. In Wellington, a team of activists climbed onto the Parliament building with solar panels in June to draw attention to the Key Government’s lack of action to combat climate change or promote clean renewable energy such as solar and wind.

In March 2016 Greenpeace invited the public to join a blockade of New Zealand’s largest oil industry conference. Hundreds of people gathered in central Auckland to block the venue’s entrances and confront oil industry executives with large images of the impacts of climate change as they arrived. This was the first time in New Zealand that Greenpeace had invited the general public to take civil disobedience action en masse.

“Peaceful civil disobedience has been successfully used throughout history in the face of huge injustices. We’re taking inspiration from people like Gandhi, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr, and the movements here in New Zealand that opposed Apartheid and made us Nuclear-Free,” said Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Steve Abel. “In the face of Government and industry inaction it’s going to take people power to secure the future we so urgently need – one that’s run on 100% clean energy.”

The mass protest came just days after news that February 2016 had been the hottest month on Earth in recorded history.

Stopping ‘The Beast’

“By 2017 the only active exploration was from East Cape to the bottom of the East Coast of the North Island. An unprecedented alliance of Hapū and iwi formed to oppose Statoil and Chevron’s oil exploration activities and they sent their double-hulled ocean-going waka, Te Matau a Māui, to challenge MV Amazon Warrior [a.k.a. The Beast],” says Greenpeace Campaigner Mike Smith (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu).

Following the arrival of MV Amazon Warrior, 80 coastal Hapū declared their unanimous rejection of oil exploration, culminating in an historic agreement by the National iwi Chairpersons Forum in November 2017 to oppose all seismic testing and oil exploration in New Zealand’s waters.

Russel Norman defies the Anadarko Amendment

In April 2017, Greenpeace sent its new boat, MV Taitu, 50 nautical miles out to sea to confront ‘The Beast’, which actor Lucy Lawless helped crowd-fund.

Once there, Greenpeace Executive Director Russel Norman and volunteer Sara Howell defied the Government’s ‘Anadarko Amendment’ legislation by diving into the water in front of the 125-metre seismic blasting ship, forcing it to make a full turn and stop its search for oil that day. By doing so they deliberately broke the ‘Anadarko Amendment’.

“[The legislation] was put in place by the Government to protect the interests of big oil and to stifle dissent. It is an anti-democratic law designed to silence the voice of reason – a collective voice that demands we stop this insane trajectory toward self-destruction; that is drilling and burning oil, which drives climate change,” said Russel Norman. “Because of our Government’s complicity with the oil industry, and its failure to protect us from dangerous climate change, we had no choice but to take action yesterday to secure our common future.”

Russel Norman, Sara Howell, and Greenpeace were charged by the oil division of the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (MBIE), under the ‘Anadarko Amendment’ and faced the possibility of a year in jail and up to $300,000 in collective fines.

Jacinda Ardern’s new Labour-led Coalition Government subsequently dropped the charges against them in 2018 and they were both discharged without a conviction, effectively making the ‘Anadarko Amendment’ redundant.

“We’re thrilled with this verdict. We see this as a major win not just for us, but for the whole movement of people fighting against fossil fuels,” said Russel Norman, responding to the news. “We love this planet and our kids, and we’ll continue to fight to protect them from oil companies that want to destroy the climate in order to make profits.”

“The science is clear – if we want our kids to have a safe climate, we can’t afford to burn most of the oil, gas, and coal we’ve already discovered. It makes no sense to look for more.”

New offshore oil and gas exploration banned

The new incoming Labour-led Coalition Government signalled in October 2017 that it was considering making 2017 the last year that a block offer would be made for new oil exploration permits at sea.

Then, after a period of intense public campaigning by Greenpeace and many others, Jacinda Ardern accepted Greenpeace’s ‘End Oil’ petition outside Parliament on 19 March 2018, which had been signed by more than 45,000 people, and the ban was voted into law on 12 April 2018.

The petition presentation event also included Greenpeace Executive Director Russel Norman, representatives from Forest and Bird, WWF, Oil-Free Wellington, OraTaiao (New Zealand Climate & Health Council), and actor Lucy Lawless.

Greenpeace described it as a huge win for the climate and for people power. It was also a reminder of the immense value of running a prolonged campaign that involved every part of the organisation from the Board, Executive Director, staff, volunteers, and supporters of Greenpeace New Zealand, to Greenpeace International and its various boats: “When we stand together, we win.”

Greenpeace Executive Director Russel Norman said the announcement ending new offshore oil and gas exploration was an “historic moment, and a huge win for our climate and people power,” and that, “This has been one of Greenpeace New Zealand’s longest running campaigns and today marks a great success for so many people.”

Looking back on the campaign, Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Steve Abel, who had been involved since it started said, “I feel proud of us doing that stuff well, we had our strategic brain on and then we just never let up. We persevered and persisted until we got it.”

“[Greenpeace New Zealand Climate Campaigner 2008-2015] Simon Boxer was crucial to our thinking on the oil campaign. He looked at the geo-politics of climate change and fossil fuels. While the global environment and climate movement was focused on coal as the dirtiest fossil fuel, Simon saw that oil was the industry with the real geo-political power. As the wealthiest and most powerful and influential industry in history, Big Oil was the real foe and the one we had to vilify and beat if we were to save the climate. The oil industry linked to sketchy US foundations that funded Bush and his anti-climate change agenda.”

“So, the real power play was taking on the power of the oil and gas industry. Simon’s power-analysis said, ‘we have to work on oil’.”

Read more of the Greenpeace oil campaign in Seven years in the wilderness by Steve Abel

‘Making Oil History’

SV Rainbow Warrior III sailed into New Zealand in September-October 2018 to celebrate the new law with its ‘Making Oil History’ tour.

The last of the big global oil companies exploring for oil and gas in deep water in New Zealand was now Austrian oil giant OMV. Since the ban, Greenpeace has ramped-up its campaign to focus on OMV both in New Zealand and Austria.

SV Rainbow Warrior III’s ‘Making Oil History’ tour included sailing to Taranaki with representatives on board from the Taranaki community to confront OMV’s drill-ship and to call on OMV to halt its operations there immediately. A “Make OMV History” banner was also displayed on SV Rainbow Warrior III.

With the future in mind, Greenpeace released its ‘Seize the Sun’ report in September 2018, which proposed solarising half a million New Zealand homes over the next ten years by using the public money that had hitherto been given to subsidise the oil and gas industry.

“Not only would this help to reduce our climate pollution, but it would put power back in the hands of New Zealanders, increase the resilience of the national grid, and lower energy bills across the board,” said Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Amanda Larsson. “We now need to urgently embark on an ambitious programme to build the new clean energy required to replace the fuels of the past. Significantly increasing the amount of home-grown clean power we generate from the sun sits at the heart of this transition.”

It was deeply disappointing, then, that the NZ Government’s Environmental Protection Authority issued an extension to an existing deep sea oil drilling permit in October 2018. Greenpeace responded by saying that it highlighted a serious loophole in the new law which needed to be removed immediately so that no other existing permits could be extended beyond their original timeframe.

“Any extension of an existing permit is essentially granting a new permit and is entirely inconsistent with climate leadership. If permit extensions like this continue, Ardern’s Government will lose international credibility,” said Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Amanda Larsson. “It’s disingenuous to claim we are one of the first countries in the world to issue a ban on oil and gas exploration while also leaving the back door open for exploration to continue for potentially decades to come.”

Then in April 2019, a new government report revealed that NZ’s carbon emissions continued to increase. Emissions rose by 2.2% between 2016 and 2017, and had risen by 23% between the 1990 baseline and 2017. This was also deeply disappointing, coming at a time when New Zealand’s emissions urgently need to be rapidly reduced to avoid the worst extremes of climate chaos.

The NZ Government passed its much-anticipated Zero Carbon Act in November 2019, which set out targets for zero net carbon emissions by 2050 and a reduction of between 24% and 47% of methane emissions by 2050.

Greenpeace described it as a hard-fought people-powered win to be celebrated, but warned that it should not become a convenient excuse for politicians to do nothing further about climate change. Its passage meant that a framework had been put in place, but the hard work is yet to be done to improve the targets and ensure its implementation.

“With a miserly ambition of 10% cuts in methane by 2030 – the gas from our dirtiest industry, dairy – the Zero Carbon Bill is watered-down medicine that lacks the potency to cure the actual ailment we have,” said Greenpeace Executive Director Russel Norman. “We’re living through a climate emergency and New Zealanders are more prepared now than ever to fight for action on it. We’ve seen a new wave of climate protests taking the world by storm. Millions of students are regularly going on strike from school to pressure their governments to act. I think if the NZ Government doesn’t get on with stopping polluting activities and backing clean energy, then we’ll see more public protest and civil resistance.”

The OMV ‘History of Oil Museum’

Backing its words with actions, a few weeks later Greenpeace was on the streets again with activists from around NZ to blockade OMV’s Taranaki HQ for three days. While there, they set up a temporary ‘History of Oil Museum’ outside the front entrance, showcasing obsolete oil rigs, petrol pumps, and petrol-powered cars – and OMV’s HQ – from the fossil-fuel era.

In Austria, local Greenpeace activists rallied alongside Māori climate activists including Greenpeace Campaigner Mike Smith, to stage a ‘mock oil spill’ event outside OMV’s head office in Vienna that was accompanied by a group of giant whale sculptures.

In April 2020, OMV announced it would indefinitely postpone its last remaining oil and gas exploration plans in the Taranaki Basin. The message from Greenpeace seemed to have been received at last.

“Now is the time to reimagine and rebuild the world we want so that when we come out the other end of this crisis, we are living in a more resilient Aotearoa,” said Greenpeace Climate Campaigner Amanda Larsson. “This starts with a rapid transition away from fossil fuels, and towards a society powered by clean, renewable energy.”

And then, in a relatively small but symbolic significant victory, the NZ Government announced in September 2020 that the New Zealand Parliament Buildings would install solar panels on the roof in a bid to cut its carbon footprint – 23 years after Greenpeace first proposed it!

Over the past three decades of campaigning to save the climate – confronting the problem and promoting solutions – Greenpeace has achieved some important victories along the way, but the reality is that New Zealand’s carbon emissions still continue to grow.

“We’re living through a climate emergency and New Zealanders are more prepared now than ever to fight for action on it,” says Greenpeace Executive Director Russel Norman. “We’ve seen a new wave of climate protests taking the world by storm. Millions of students are regularly going on strike from school to pressure their governments to act.”

“I think if the New Zealand Government doesn’t get on with stopping polluting activities and backing clean energy, then we’ll see more public protest and civil resistance.”