Nuclear Campaign

Origins

The Nuclear Campaign was Greenpeace’s first campaign in New Zealand. It initially grew out of the anti-nuclear and anti-war movements of the late 1960s, especially in Canada where there were large numbers of anti-war US draft resisters and a large student movement that mobilised against US involvement in the Vietnam War, and nuclear weapons testing in the Aleutian Islands.

French nuclear testing

In New Zealand the Nuclear Campaign started with the first protest flotilla mobilisation to oppose and disrupt the French Government’s atmospheric nuclear weapons testing programme at Moruroa Atoll in Te Ao Maohi/French Polynesia in 1972. That was led by sailing vessel (SV) Greenpeace III (previously named SV Vega), which was crewed by David McTaggart, Anna Horn, Nigel Ingram, and Ben Metcalfe (who represented the Greenpeace Foundation of Canada), and which also included SV Tamure, SV Boy Roel and SV Magic Isle.

Then in 1973 a second larger flotilla sailed there from New Zealand including SV Fri, crewed by owner David Moodie, navigator Martini Gotje, Rien Achterberg, Rua Paul, Naomi Peterson, Ted Rutter and others, as well as SV Vega, which was this time crewed by David McTaggart, Anna Horne, Nigel Ingram and Mary Lornie. The other boats that sailed from New Zealand were SV Spirit of Peace, SV Bluenose, SV Barbary, SV Arakiwa, and SV Tanea. In addition, SV Malaguena and SV Warana sailed from Australia, SV Carmen from Tahiti, and a few other boats sailed from Fiji, Samoa, and Peru. Only SV Fri, SV Vega and SV Spirit of Peace were able to make it as far as Moruroa.

New Zealand Prime Minister Norm Kirk also sent the navy frigate HMNZS Otago to Moruroa to oppose the nuclear tests there, which in turn was relieved by HMNZS Canterbury.

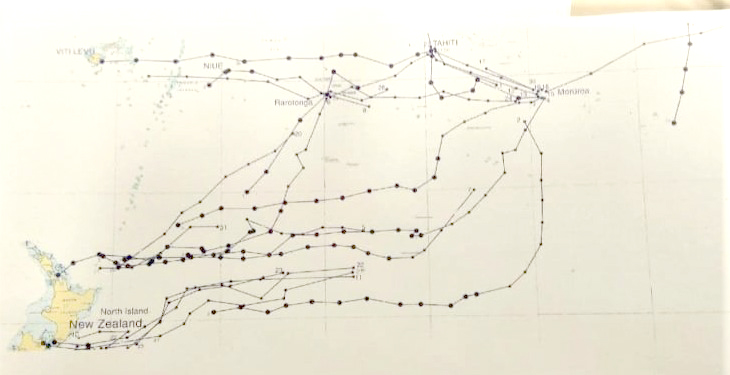

In 1974, coordinated by the newly incorporated Greenpeace New Zealand, SV Fri embarked on an epic three-year 40,000-km “Pacific Peace Odyssey” voyage from New Zealand, carrying the nuclear-free message to all of the nuclear weapons states. They met with officials and political leaders, and visited schools, workplaces, and public venues to speak about their nuclear-free message of peace, sometimes planting trees to commemorate their visit. The voyage included notable visits to Tahiti (Te Ao Maohi/French Polynesia), the Republic of the Marshall Islands (a UN Trust Territory administered by the USA at the time), the city of Hiroshima in Japan where the first nuclear weapon was used by the USA in August 1945, Nahodka (Soviet Union), Shanghai (China), Hong Kong (UK Territory), and Chennai (India).

The protest flotillas of 1972 and 1973, and a legal case taken to the International Court of Justice in The Hague by the NZ Government resulted in the French Government ending the atmospheric nuclear tests in 1975 by moving them inside Moruroa Atoll, into shafts drilled down through the coral into the underlying rock below the waters of the atoll’s lagoon.

Greenpeace’s long-term campaign strategy was to end nuclear testing as a step to stopping the endless production and modernisation of new nuclear weapons systems through a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Later, that extended to stopping the spread of nuclear weapons systems into space, which started to happen with the US Star Wars weapons programme in the 1980s, and included new ‘exotic’ space-based weapons designed to intercept and shoot down nuclear missiles as they hurtled towards populated targets on the Earth’s surface.

The US Star Wars programme had the effect of intensifying the nuclear arms race and gave added incentive for each side to develop a pre-emptive first strike nuclear attack capability against the other side before they had reliable anti-ballistic missile systems in place. The massive size of the two superpowers’ nuclear arsenals at that time – about 25,000 nuclear weapons each – meant that a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union would have wiped out life on Earth.

Nuclear-Free New Zealand

New Zealand had always been an important country for Greenpeace’s Nuclear Campaign because it was on the frontline of the campaign against nuclear weapons testing, nuclear ship visits, and the use of nuclear energy.

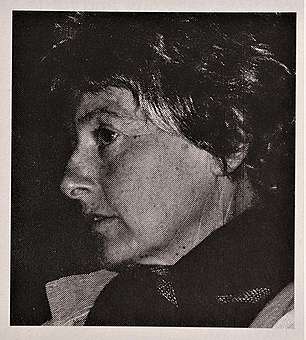

The nuclear campaign was led by Elaine Shaw for much of the late 1970s and the 1980s. Her presence was a thread from the days of SV Fri, and she repeatedly invited Greenpeace International to send the Rainbow Warrior to New Zealand to join the campaign against the French Government’s nuclear testing programme.

Along with the rest of the peace movement, Greenpeace opposed US and British nuclear ship visits to New Zealand, and campaigned for the Nuclear-Free legislation that was eventually passed by David Lange’s Labour Government in 1987.

Elaine Shaw was there to welcome the Rainbow Warrior when she sailed past Rangitoto Island into Auckland in 1985, and lived to see New Zealand declared nuclear-free in 1987. Sadly, she died of cancer in October 1990, so she did not live long enough to see the end of the French Government’s nuclear testing programme at Moruroa Atoll.

Greenpeace continued its campaign by working to defend the nuclear ships ban from attempts to overturn it by the opposition NZ National Party (1987-1990), and then when National formed a new Government that floated the idea that the nuclear-free legislation might be watered-down by removing nuclear-powered submarines (1990-1993). Led by Jaqui Barrington, the campaign organised a series of Nuclear-FreeCup races on Waitemata Harbour through that period which helped fly the flag of the many nuclear-free flotilla yachts that had sailed out to protest the visiting nuclear-ships in the 1970s and 1980s.

These were successful in keeping the issue in the public eye and National backed off its mooted changes to the nuclear-free legislation.

History of nuclear testing in the Pacific

About 325 nuclear weapons were detonated in the Pacific region by the governments of the USA, Britain and France between 1946 and 1996. The total cumulative explosive yield was about 173.8 megatons, which is the equivalent of about 11,600 Hiroshima bombs.

As a result of the massive amount of radioactivity released by the atmospheric tests spreading across the globe, it has been estimated that there were about 430,000 additional cancer deaths globally due to cumulative radiation doses by the year 2000.

In the long term, it has been estimated that at least 2 million additional cancer deaths are expected globally due to the longevity of many radioactive isotopes.

Read more about the full history of nuclear testing in the Pacific

The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior

Greenpeace’s flagship Rainbow Warrior sailed from North America into the Pacific region in 1985 to help relocate the people of Rongelap in the Marshall Islands whose home had been contaminated by the US Government’s atmospheric nuclear weapons tests there in the 1940s and 50s, to protest against the US Star Wars missile testing programme there, and to visit Vanuatu and New Zealand before setting out to lead protests against French nuclear weapons testing at Moruroa.

A team of French Government DGSE agents bombed SV Rainbow Warrior while it was at Marsden Wharf in Auckland on 10 July 1985, sinking Greenpeace’s flagship and killing Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira who was on board.

It was an outrageous and cowardly attack designed to stop Greenpeace from sending the Rainbow Warrior to lead a new campaign against the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme at Moruroa Atoll in Te Ao Maohi/French Polynesia.

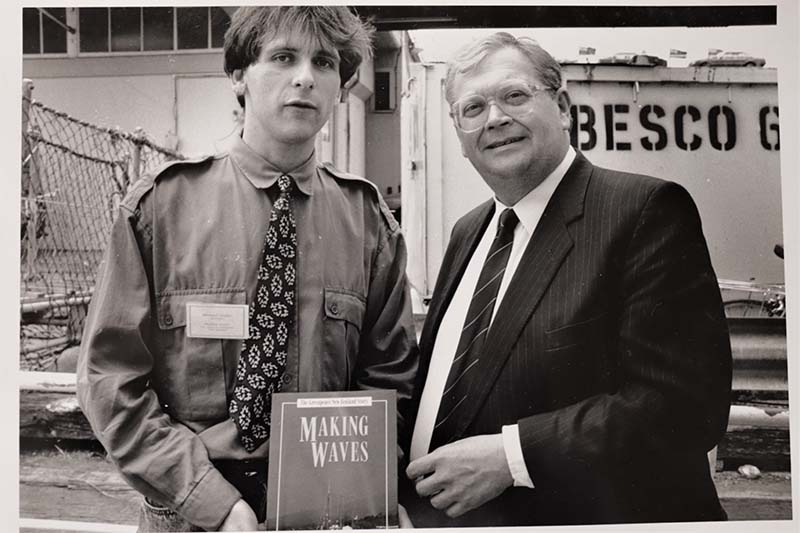

The attack shocked the entire country and was a defining moment in the life of the nation. Details about what happened after the bombing are set out in the timeline attached to this project and in the Making Waves book.

Two of the French DGSE bombers – Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieur – were arrested by NZ police 30 hours after the bombing, and charged with Fernando Pereira’s murder. They subsequently pleaded guilty to manslaughter charges and were sentenced on 22 November 1985 to ten years in prison.

After a 1986 United Nations arbitration process the French Government agreed to pay $8.16 million in compensation to Greenpeace to replace the Rainbow Warrior, and a much smaller compensation amount to Fernando Pereira’s wife, their two children, and his parents.

The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior in downtown Auckland is infamous for being the only time that a foreign government (supposedly an ally) has carried out a terrorist attack in New Zealand.

In September 1985, Greenpeace sent MV Greenpeace to protest against the French Government’s nuclear testing programme at Moruroa Atoll alongside a flotilla of New Zealand protest boats including SV Vega, SV Alliance, SV Varangian, and SV Breeze.

Greenpeace continued to commemorate the anniversary of the 1985 bombing of the Rainbow Warrior, and participated in the unveiling of a Rainbow Warrior Memorial at Matauri Bay in Northland in 1990.

Since the permanent memorial was unveiled there, more commemorative events have been held at Matauri Bay, including on the occasion of visits of SV Rainbow Warrior II there in 1995 and 2005, and SV Rainbow Warrior III there in 2013 and 2018.

Rainbow Warrior bomber Gerard Andries goes free

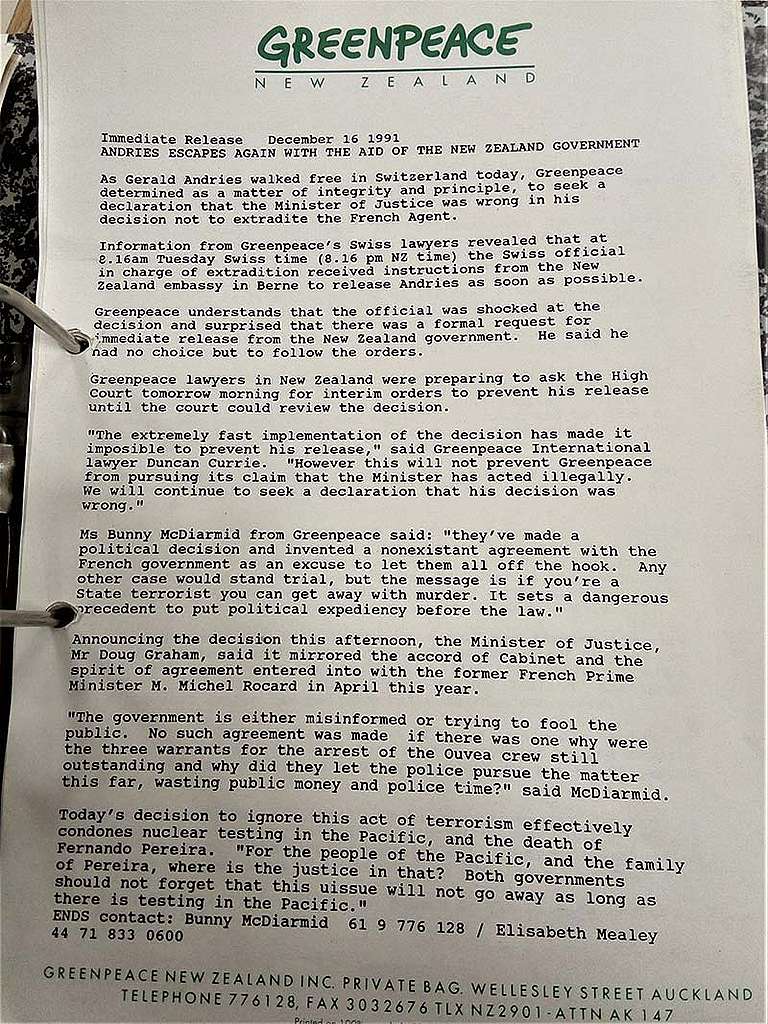

On 26 November 1991 Swiss police arrested and held French DGSE Rainbow Warrior bombing team leader Gerald Andries on an outstanding 1985 Interpol warrant as he tried to enter Switzerland from France.

Three weeks after Andries’ arrest, NZ Justice Minister Doug Graham announced that the Jim Bolger-led National Government had made the shameful decision not to seek Andries’ extradition to stand trial in NZ.

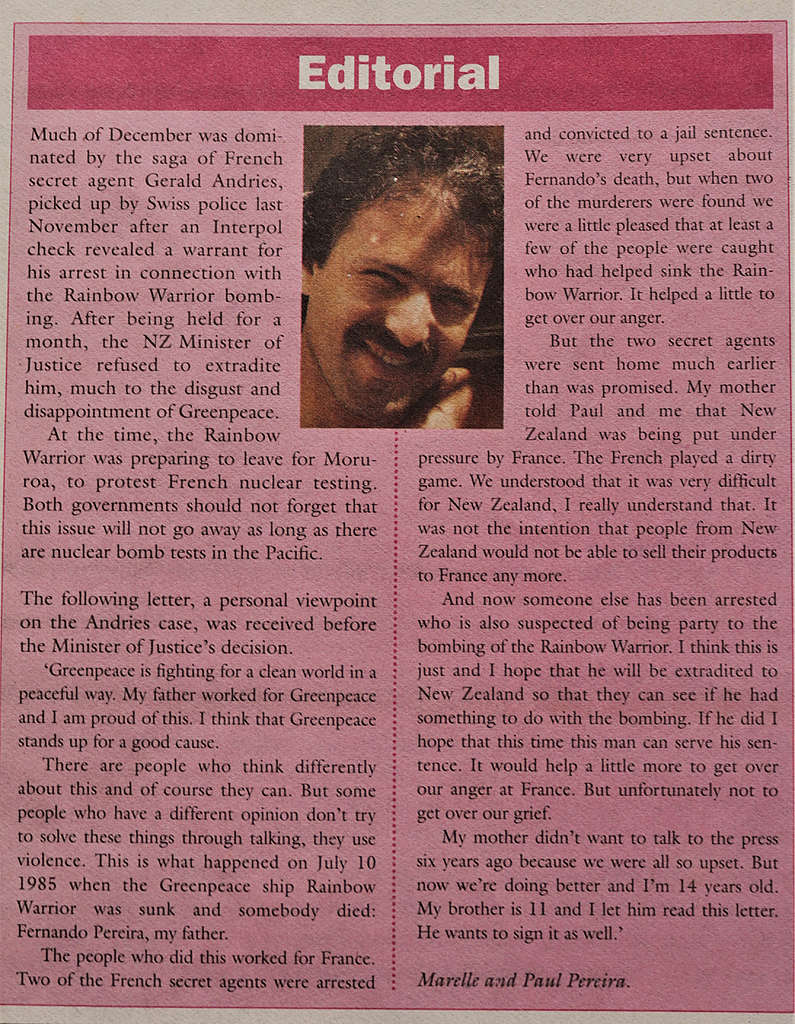

Fernando Pereira’s children Marelle and Paul Pereira sent a letter to Doug Graham prior to his decision, which Greenpeace published following his announcement that there was to be no extradition request.

There is no other example in the history of New Zealand in which the government of the day declined to seek the extradition of a suspect in a terrorist attack after their detention overseas on an Interpol arrest warrant.

Andries subsequently walked free on 16 December 1991. Greenpeace International Legal Counsel Duncan Currie said, “… this will not prevent Greenpeace from pursuing its claim that the minister has acted illegally. We will continue to seek a declaration that his decision was wrong”.

Greenpeace Pacific Campaign Co-ordinator Bunny McDdiarmid said that the minister’s decision to ignore, “this act of terrorism effectively condones nuclear testing in the Pacific, and the death of Fernando Pereira. For the people of the Pacific, and the family of Fernando Pereira, where is the justice in that?”

The new Rainbow Warrior sails to Moruroa

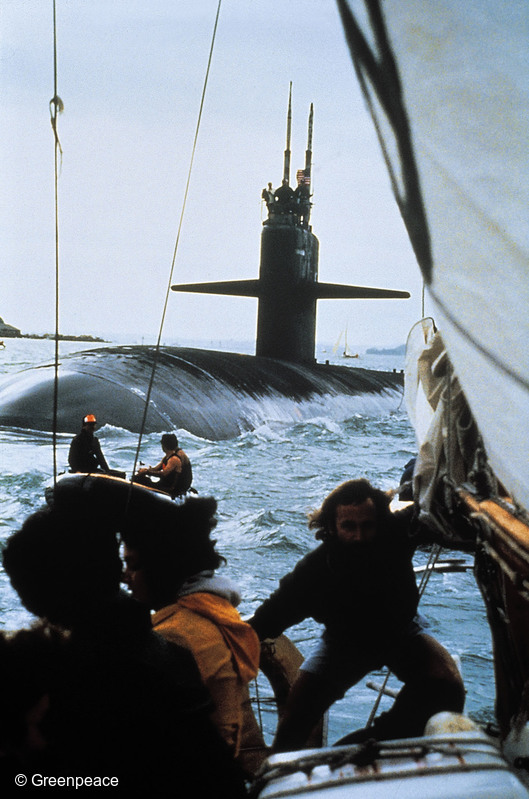

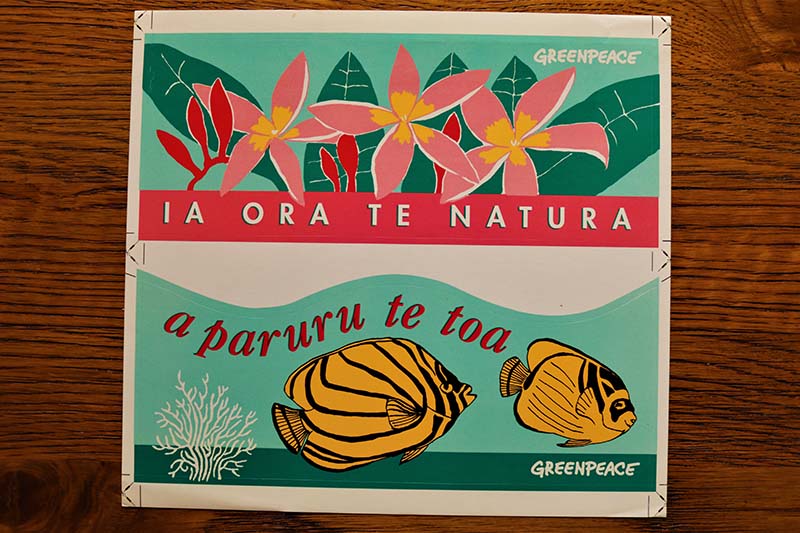

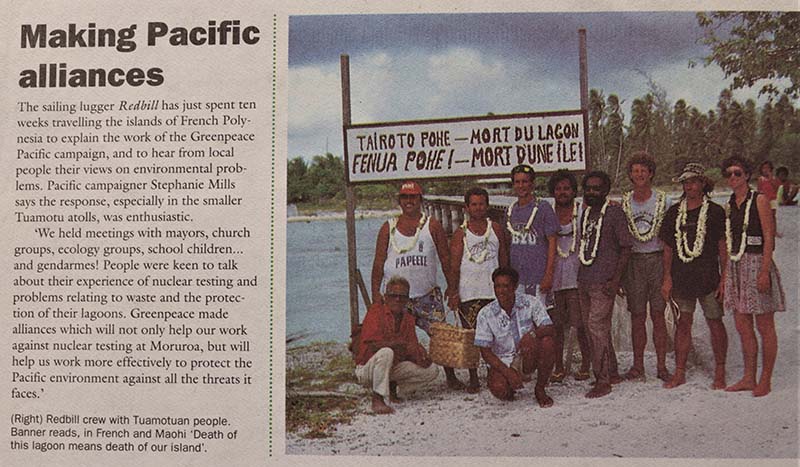

Greenpeace’s campaign against the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme continued through the period 1990-1996, including a series of SV Rainbow Warrior II expeditions to the test site at Moruroa Atoll in 1990, 1992, and 1995, and a tour of Te Ao Maohi/French Polynesia by SV Redbill in 1991 to meet with local communities there and discuss a range of environmental issues including nuclear testing and climate change.

Greenpeace also published a series of reports including the testimonies of workers and civilians affected by radioactive contamination from the tests, a chronology of the nuclear testing programme, and the results of Greenpeace’s own environmental sampling work at sea off Moruroa Atoll (the indigenous Maohi spelling is ‘Moruroa’ but the French military incorrectly spelled it ‘Mururoa’).

Witnesses of French nuclear testing in the South Pacific

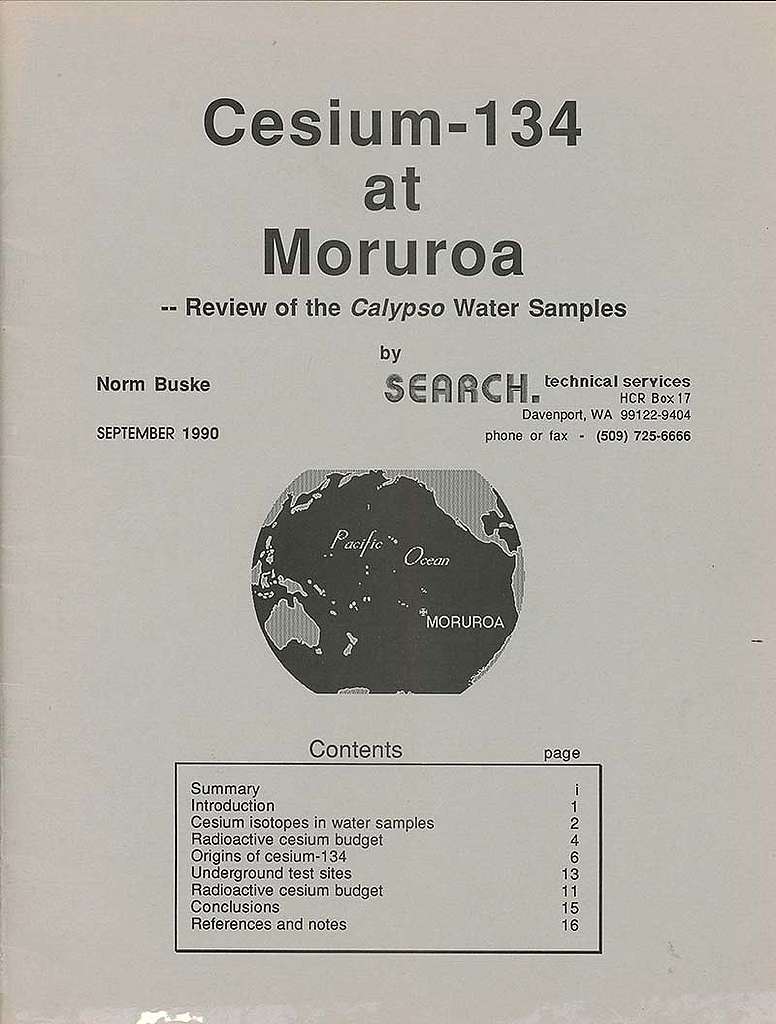

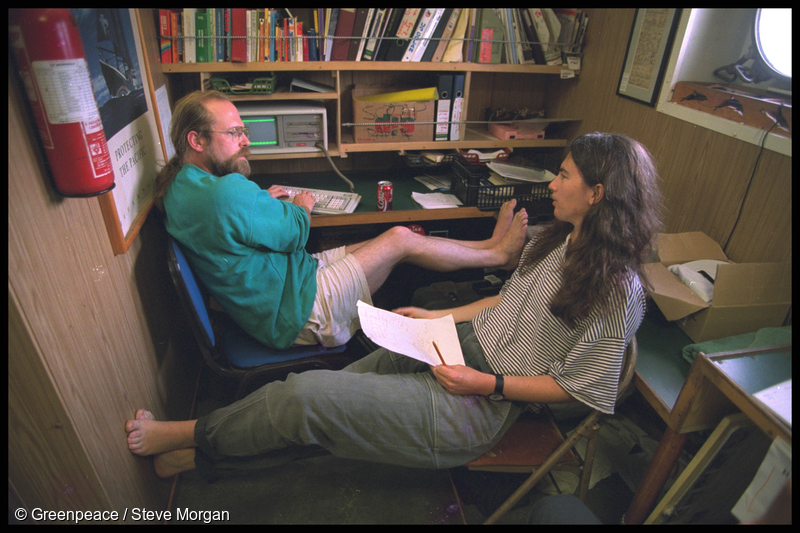

SV Rainbow Warrior II visited Papeete in December 1990 before sailing to Moruroa where she was closely shadowed by three French navy warships. US scientist Norm Buske and Kiwi scientist Bruce Gabites were on board to take sea water and plankton samples just outside the 12 nautical mile exclusion zone off Moruroa and to measure the local sea currents.

During their analysis on board SV Rainbow Warrior II of the samples that they collected at sea, they found radioactive Caesium-134 and Cobalt-60 in plankton, both isotopes being by-products of a nuclear explosion. This was evidence, said Greenpeace, that confirmed Moruroa Atoll was leaking radioactivity into the seas around it and entering the marine food chain.

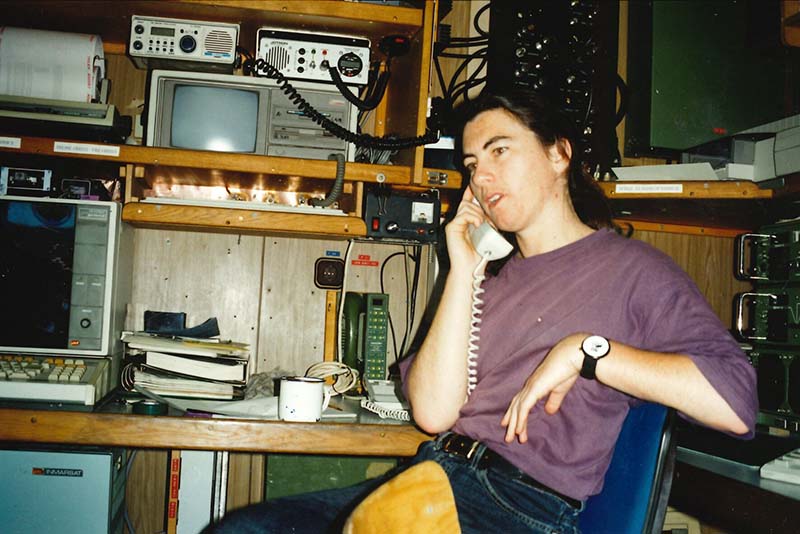

“The phone has rung every five minutes for the past twenty-four hours – during the day from Pacific, New Zealand, and Australian press, during the night the Europeans. I sleep in the radio room, or rather sprawl uncomfortably on the seat, closing my eyes briefly between calls,” said Greenpeace Nuclear Test Ban Campaigner on board, Stephanie Mills.

News of the findings was broadcast on the two main TV channels in France, accompanied by video footage of large cracks in the coral crown inside Moruroa lagoon shot in 1988 by Jacques Cousteau.

When the two scientists tried to repeat their sampling of plankton their inflatable boat was shadowed by the French Navy frigate Lavalee, which deployed 40 commandos in four high speed boats to seize the Greenpeace scientific team and forcibly remove them to the French frigate for interrogation. They were then taken to the military base on Moruroa and held there incommunicado and under military guard for three days.

While the scientific team was detained at Moruroa, Greenpeace France activists scaled Notre-Dame Cathedral in the centre of Paris to hang a large banner calling for an end to nuclear testing, and a Greenpeace delegation visited the Ministry of Defence demanding to see French Defence Minister Jean-Pierre Chevènement. There were also protests outside French embassies in New Zealand, Australia, USA, and Canada calling for an end to the tests and the immediate release of the scientific team.

A large anti-nuclear testing protest rally was also organised in Papeete. SV Rainbow Warrior II returned to Papeete to join the protest rally. Shortly after that, the boat sailed to Auckland to get the samples to a NZ laboratory for further analysis and storage.

France joins the nuclear testing moratorium

When SV Rainbow Warrior II returned to the French military exclusion zone at Moruroa on 27 March 1992, five French navy warships, two helicopters, and dozens of masked commandos tried to stop it from reaching Moruroa Atoll.

A second Greenpeace boat, SV Fand, sailed from New Zealand to Moruroa, arriving there at the same time as SV Rainbow Warrior II.

“I sailed from New Zealand to Moruroa on Chris Robinson’s yacht SV Fand in 1992 with Chris, Lloyd Anderson – who was our radio operator on the original Rainbow Warrior in 1985 – and Kitty Rangimaire Smith,” recalls Henk Haazen. “There were some other boats that set out but SV Fand was the only one to reach Moruroa and rendezvous with SV Rainbow Warrior II there. Chris had built SV Fand to the same plans as SV Vega.”

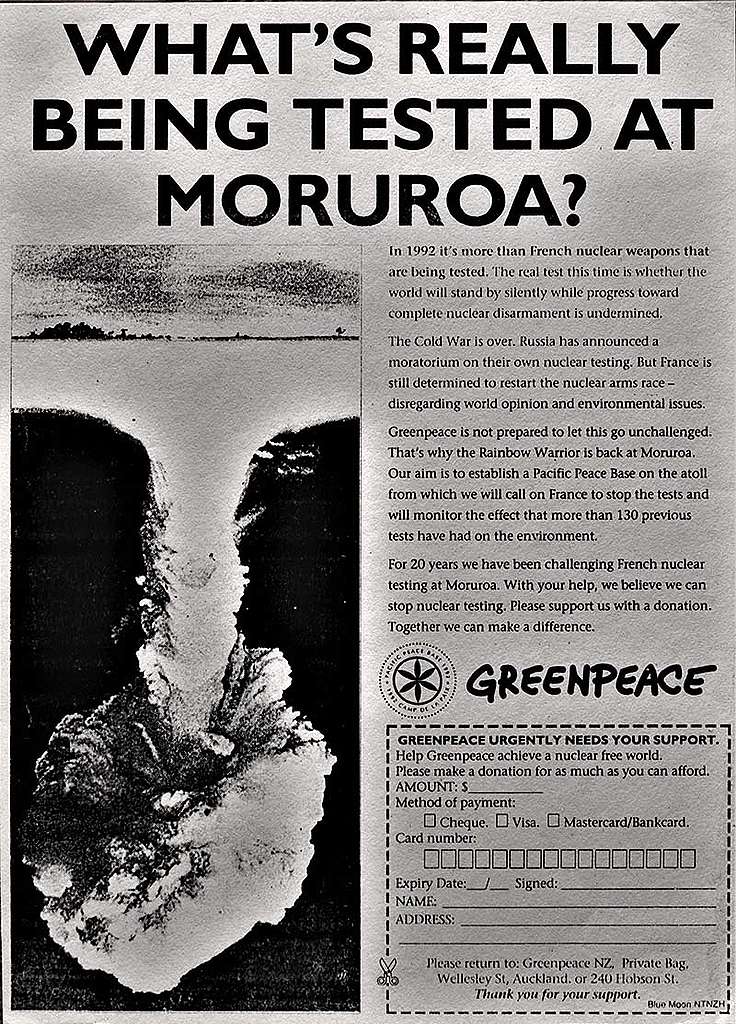

“The campaign publicly announced that Greenpeace would attempt to land on the atoll and establish a Moruroa Peace Base, urging France to stop testing and allow a full independent international scientific assessment of radioactive leakage into the lagoon,” recalls Stephanie Mills, who was Greenpeace Nuclear Test Ban Campaigner on board at the time.

After a 90-minute high speed chase, the French armed forces arrested Greenpeace’s inflatables and sent 20 commandos to board SV Rainbow Warrior II and take control of the boat.

“Our voyage, timed to coincide with elections in France, also forced a new political response there. French Environment Minister Brice Lalonde called on his own government to take an initiative at the Earth Summit to end nuclear testing. The French Green Party, fresh from success in the elections, also whole-heartedly endorsed our campaign,” says Stephanie Mills.

Two weeks after the arrest of SV Rainbow Warrior II and the expulsion of crew members and campaigners on board, French President Francois Mitterand announced that France would join the moratorium on nuclear weapons testing that had been declared by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in October 1991.

The US and UK joined the moratorium the next year and progress started to be made towards agreement on a Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty through the UN.

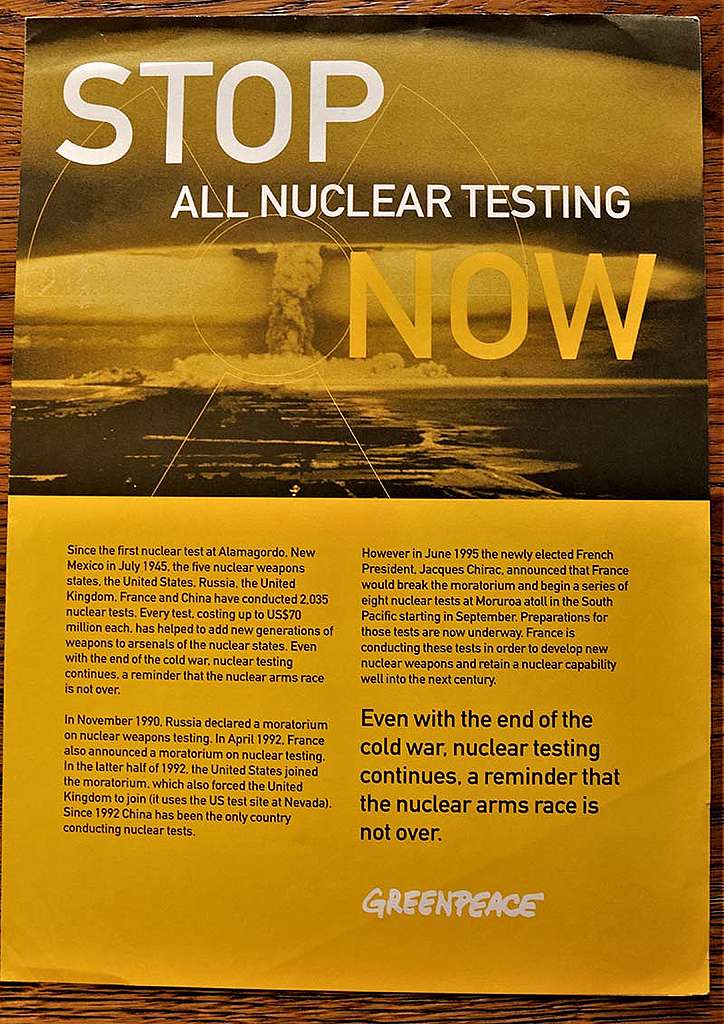

The moratorium was derailed by two events in May 1995. The first was the indefinite extension of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty without any requirement for the five declared nuclear weapons states to undertake nuclear disarmament.

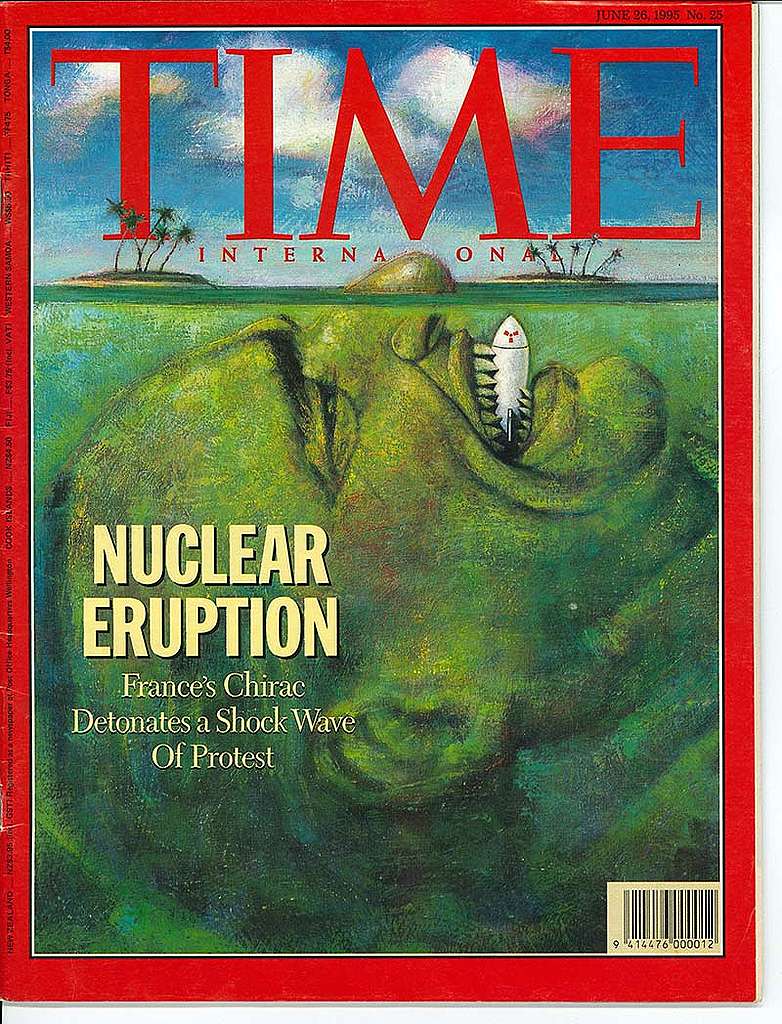

The second was the election of ‘Gaullist’ politician Jacques Chirac to the French Presidency after the end of Francois Mitterand’s second term in office, and Chirac’s subsequent decision to resume the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme at the same time that the Chinese Government also did so.

The storming of the Rainbow Warrior

Chirac’s decision to resume the tests prompted Greenpeace to announce that it would send SV Rainbow Warrior II to lead renewed protests against the nuclear tests at Moruroa Atoll. En route to Moruroa, SV Rainbow Warrior II visited the Cook Islands and Tahiti where there were big public rallies against the nuclear tests that brought thousands onto the streets of the capitals, Avarua and Papeete.

A few days later, the world watched as dramatic events unfolded on 10 July 1995, the tenth anniversary of the bombing of the original Rainbow Warrior by French DGSE agents in Auckland.

While SV Rainbow Warrior II was pursued and rammed by French warships, armed French commandos stormed the Greenpeace flagship as it sailed into the military exclusion zone around Moruroa Atoll. Once on board, the commandos detonated tear gas grenades and smashed their way into the communications compartment to stop Greenpeace from broadcasting footage of the events on board.

Greenpeace campaigners Stephanie Mills and Jean-Luc Thierry, and Radio Operator Thom Looney locked themselves in the radio room and were broadcasting live, describing the violent seizure of Greenpeace’s flagship. Speaking live to the BBC World Service, Stephanie Mills said: “Our peaceful protest is unstoppable. We know the French military have far greater resources than Greenpeace, but international public opinion is on our side.”

SV Rainbow Warrior II‘s crew were arrested and taken to Moruroa where they were interrogated by military police for 15 hours. They had hidden their passports aboard SV Rainbow Warrior II before the boat was boarded, so when asked for their names they all identified themselves as Fernando Pereira, the Greenpeace photographer who was killed when agents of the French DGSE bombed the original Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour on 10 July 1985.

Unable to identify their names, the French military took them back to SV Rainbow Warrior II at 2am and the boat was towed out of Moruroa lagoon back into international waters where it was released.

At the time that SV Rainbow Warrior II had been boarded by the French commandos, four Greenpeace inflatable boats sped towards the lagoon at Moruroa to the test drill rig there. Two of the three boats that made it into the lagoon each managed to land an activist who occupied the test drilling rig.

“Kate Lecchi and I drove along the drilling platform, chased by a military helicopter, and got underneath the drilling rig,” recalls SV Rainbow Warrior II crew member Alice Leney.

“I jumped up and climbed onto the rig with a steel tube slung over my back and got onto a walkway and then ran up some stairs onto the platform where I found a railing and attached myself around the railing by securing my arms in the steel tube. The military had to come after me and then once they got to me, they had to work out a way to get me off the rig, which took them quite a while.”

“Eventually they came back with a sharp knife and cut the device that I was attached to inside the steel tube. Then they arrested and removed me.”

Landing activists onto the drilling rig to disrupt preparations for the first nuclear test had been the primary aim of the action, so Alice Leney was successful in doing so.

A fifth inflatable crew from SV Vega comprising Moruroa protest veterans David McTaggart, Henk Haazen and Chirs Roberston, also managed to evade the French military and disrupted their operations for weeks by hiding on a nearby small island in the vicinity of Moruroa with support from SV Vega skipper Steve Sawyer.

The Pacific Peace Flotilla

The disproportionate violent response of the French military to Greenpeace’s flagship sailing into Moruroa sparked global outrage, triggering protests across the world.

A new Pacific Peace Flotilla was formed comprising dozens of small boats that soon set sail from New Zealand, Tahiti, Cook Islands, Fiji, USA, and Chile to join SV Rainbow Warrior II off Moruroa, and a petition launched against the tests was delivered by Greenpeace to French President Jacques Chirac in Paris, signed by five million people worldwide.

In the aftermath of the storming of the Rainbow Warrior, the governments of 160 countries protested to the French Government against the planned nuclear tests.

The planned resumption of the nuclear testing programme was condemned by the Commonwealth Heads of Government, the European Parliament, South Pacific Forum leaders, and the Australian and New Zealand governments and parliaments. This left Chirac’s new French Government diplomatically isolated.

On an official visit to the European Parliament at Strasbourg in France the following day, French President Chirac was met with such strong opposition to his decision to resume nuclear testing at Moruroa that after being jeered and booed by European MPs he was stunned into silence, and was unable to begin his opening speech for a full ten minutes.

There was also a dramatic change in public opinion towards nuclear weapons in Europe. Opposition to the nuclear tests was running at 80-90% across Europe, while more than 75% of Europeans said they opposed France’s proposal for a new ‘Eurobomb’. Within Metropolitan France, 64% of people now opposed the tests.

In the face of overwhelming public opposition to the tests in New Zealand and under pressure from Greenpeace and opposition parties, the Jim Bolger-led National Government agreed to send a New Zealand navy vessel – HMNZS Tui – to support the Pacific Peace Flotilla at Moruroa.

When SV Rainbow Warrior II returned to Tahiti for repairs on 14 July there was a big display of public support for Greenpeace and opposition to the nuclear tests. A mass mobilisation of 15,000 people rallied, bringing the capital, Papeete, to a standstill for three days. Greenpeace campaigners and crew members marched alongside Maohi anti-nuclear independence leader Oscar Manutahi Temaru.

After repairs, SV Rainbow Warrior II returned to Moruroa where it made rendezvous with SV Vega, MV Greenpeace, and Te-au-Tonga, the vaka sent to join the protests by the Government of the Cook Islands.

In August 1995, the New Zealand Government also took a legal case against the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme to the International Court of Justice (The World Court). Greenpeace Legal Counsel Duncan Currie developed the idea with the support of the late international lawyer Elihu Lauterpacht to revisit the UN International Court of Justice (ICJ) decision made on French nuclear testing in 1974.

“I spoke to the NZ Government and the Leader of the Opposition to bring the case. Helen Clark, Leader of the Opposition, took a close interest, phoning me to discuss it and taking it on within Wellington. Later on I was invited to a meeting at the Beehive to discuss it. Prime Minister Jim Bolger and others took the view, espoused by Helen Clark, that New Zealand had to be seen to be doing everything it could to try to stop the tests. NZ officials were by and large opposed initially, but once the case was underway in the Hague, they realised how much international prestige it brought.”

Although the World Court ultimately ruled against taking the case any further on the basis that the bomb tests were being detonated underground rather than in the atmosphere as they had been in 1974, it added to the diplomatic pressure on the French Government to stop nuclear testing.

The Rainbow Warrior delays the first nuclear test

On 1 September, the day the first nuclear test was planned, SV Rainbow Warrior II once again set sail into the lagoon at Moruroa, launching its inflatable boats with activists aboard who sped towards the test shaft drilling rig.

Dramatic scenes were filmed from MV Greenpeace’s helicopter and broadcast around the world. Greenpeace inflatable boats once again made it to the lagoon and some crew members managed to land and evade capture by the French military.

This meant the French military had to spend days chasing around the atoll in pursuit of these activists. As a result, Greenpeace successfully disrupted and delayed the first test until 5 September.

During the 1 September protest action, armed French commandos once again boarded and stormed SV Rainbow Warrior II as it sailed into the lagoon, but this time they went further by illegally boarding and seizing MV Greenpeace outside the 12-mile military exclusion zone, and illegally impounded both of Greenpeace’s boats. The crew members and campaigners were also detained illegally for a week by the military on Hao Atoll.

Around the world people took to the streets to protest outside French embassies and consulates. When news of the 5 September test explosion at Moruroa reached Papeete there was widespread anger and the ‘Tahitian bomb’ also exploded.

Thousands of Tahitians took to the streets in protest and in parts of Papeete there were clashes with armed French riot police. During the clashes Papeete International Airport caught fire and burned, forcing its closure. Buildings in the French High Commission compound in the centre of Papeete, a visible symbol of French rule, also became the target of concerted protest in the capital.

The Flotilla and indigenous Maohi continue the campaign

SV Vega and the dozens of yachts in the Pacific Peace Flotilla that sailed to Moruroa continued their protest there, with SV Manutea acting as their floating ‘HQ’ and supported by a land-based Greenpeace team in Papeete led by New Zealander Janet Dalziell that helped to organise logistics and resupplies.

Another protest action was carried out on 16 September when two members of the Tahitian NGO Hiti Tau (Time to Act) joined Flotilla crew members aboard SV R. Tucker Thompson. One of them was a worker at Moruroa and the other had ancestral links to Moruroa and Fangataufa. They paddled to Moruroa in a traditional piragua or outrigger canoe to highlight the lack of medical monitoring of the many workers at Moruroa.

A few days later, two Flotilla crew members paddled sea kayaks into the lagoon at Moruroa until a French military helicopter found and arrested them.

Janet Dalziell helped organise for a group of eight parliamentarians from Australia, Japan, Sweden, Italy and Luxembourg on board SV Machias to sail into Moruroa on board SV La Ribaude to protest against the nuclear tests.

Once inside the exclusion zone the eight parliamentarians read out statements of protest over the radio in their respective languages, which journalists on board HMNZS Tui then recorded and broadcast around the world.

SV Machias made a second return trip from Tahiti to Moruroa with a group of seven Tahitians, mostly from Oscar Manutahi Temaru’s Tavini Huiraatira movement, who transferred onto SV Vega where they joined a group of indigenous Maohi from the nearby island of Tureia.

On 26 September 1995, David McTaggart and Steve Sawyer on board SV Vega assisted the indigenous Maohi from Tureia and Papeete in their attempt to land on and reclaim Moruroa Atoll in protest against French nuclear colonialism. A few miles inside the exclusion zone, French commandos boarded SV Vega and arrested them all.

Henk Haazen and Sanai Shida also took an inflatable boat from SV Vega and drove it to Fangataufa Atoll to try to stop one of the tests there. They too were arrested and flown to Papeete for deportation to New Zealand.

Faced with further determined protest action from the Pacific Peace Flotilla, the French Government once again resorted to piracy, and illegally seized Greenpeace USA’s SV Manutea in international waters on 2 October.

The last two Flotilla yachts left, SV Caramba and SV Joie, remained off Moruroa until the end of October when the approaching tropical cyclone season finally forced them to depart.

More New Zealand protests and CHOGM

The 5 September nuclear test and all the subsequent ones were also met with loud protests in New Zealand. Greenpeace activists blockaded the French Ambassador’s residence in Wellington and occupied the roof where they switched on loud sirens and waved anti-nuclear placards and French flags painted with a large radiation symbol.

They also protested ‘bound and gagged’ outside the French Embassy in Wellington calling for the release of the Greenpeace crews and campaigners who were being held at Hao Atoll, and blockaded the entrance.

Thousands joined a ‘Major Disgrace’ rally in QEII Square in Auckland on 9 November to condemn visiting British Prime Minister John Major for his support for the French Government’s resumption of nuclear testing.

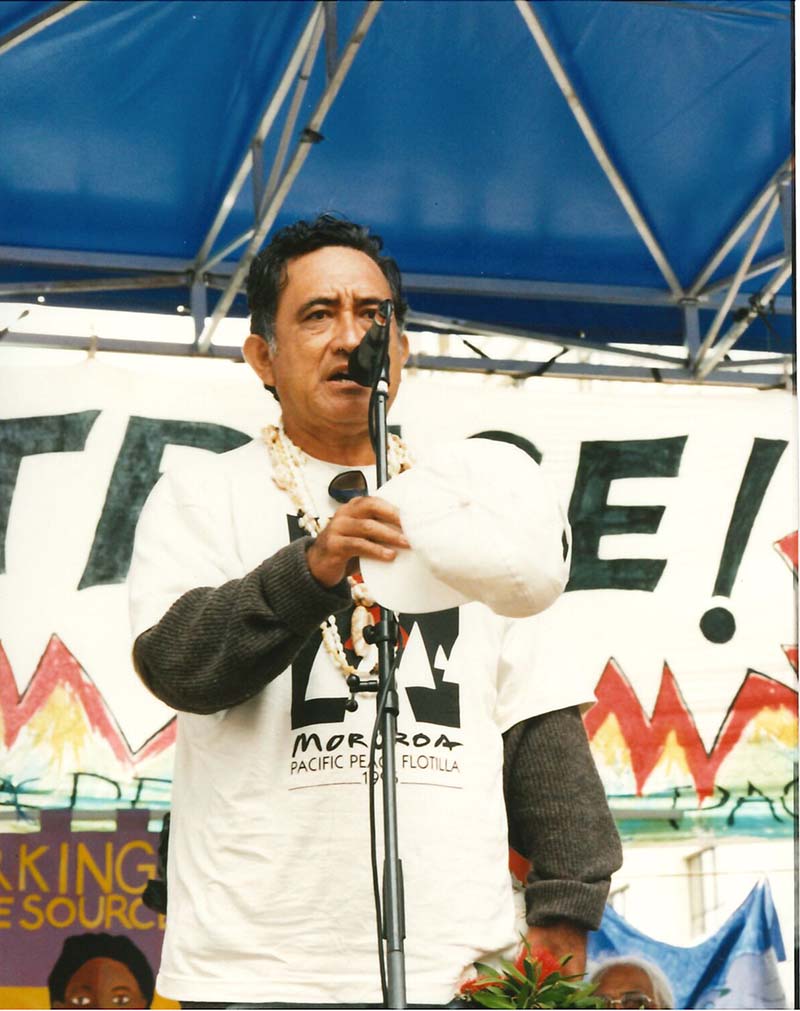

After the mihi and opening speech by Greenpeace’s Mana Tangata iwi Liaison Grant Pakihana Hawke, speaker after speaker condemned the resumption of nuclear testing, including Tahitian anti-nuclear leader Oscar Manutahi Temaru, NZ Alliance Party leader Jim Anderton, NZ First Party leader Winston Peters, Māori land rights activist Eva Rickard, and Greenpeace Test Ban Campaigner Stephanie Mills. The speeches were followed by performances by musicians Dave Dobbyn and Emma Paki.

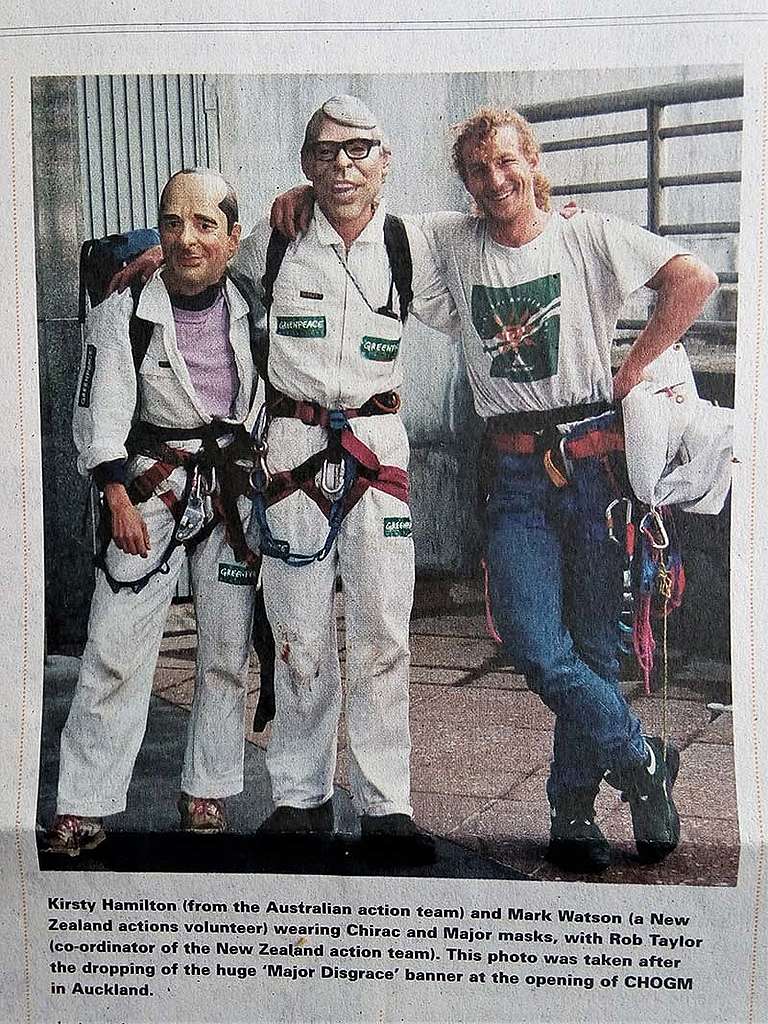

The next day Greenpeace Actions Coordinator Rob Taylor and climbers Mark Watson and Kirsty Hamilton marked the opening of the 1995 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in downtown Auckland by abseiling off the top of the 16-storey AUT Tower opposite the Aotea Square venue and hanging a giant banner that read, ‘Major Disgrace’. The banner also had a large image of the ‘Union Jacques’ flag with the face of Jacques Chirac painted in the centre of the British flag.

The banner was unfurled as world leaders started to arrive at the front entrance of the Aotea Centre, including British Prime Minister John Major, HRH Queen Elizabeth II, South African President Nelson Mandela, and NZ Prime Minister Jim Bolger.

The Greenpeace climbers wore John Major and Jacques Chirac masks and the banner remained in place for several hours for all Commonwealth leaders and their delegations to see as they arrived at the Aotea Centre venue.

It had been widely anticipated that British Prime Minister John Major would refuse to join with the rest of the Commonwealth Heads of Government in condemning the resumption of the French Government’s nuclear weapons tests because the UK and France had signed a new deal the week before that increased nuclear collaboration between the two nuclear weapons states.

Greenpeace’s banner was aimed at pointing out how the new ‘entente nucleaire’ between Britain and France meant that the UK Government had chosen its nuclear alliance with the French Government over its long-standing ties with New Zealand and the rest of the Commonwealth.

Greenpeace Campaign Manager Michael Szabo, who attended the CHOGM meeting inside the Aotea Centre as an NGO representative, was able to encourage the government delegations inside to make a strong statement condemning the nuclear tests and calling for an international treaty banning all nuclear tests and nuclear weapons.

“The CHOGM leaders’ statement issued at the end of the meeting contained all the key points that Greenpeace wanted to see in it. The fact that it came in the form of an unprecedented special ‘Statement on Disarmament’ included in the final communique was a bonus,” recalls Michael Szabo. “The statement was too strong for John Major so he refused to sign it. Then in an arrogant outburst after the session on nuclear testing, he attacked the statement as ‘inconsistent and unbalanced’ and accused all the other Commonwealth leaders of being ‘out of touch with the real world’.”

On 21 November 1995 a team of Greenpeace activists protested against the fourth French nuclear test of the year by climbing up onto and occupying the roof of the British High Commission in downtown Wellington.

Wearing John Major and Jacques Chirac masks and waving ‘Union Jacques’ flags with Chirac’s face painted on them, the activists switched on loud sirens to draw attention to the British Government’s support for the French Government’s nuclear weapons testing programme, and the new nuclear collaboration deal that the two countries had signed just a few weeks before.

French Government ends nuclear testing

The last nuclear test at Moruroa was on 27 January 1996. A team of Greenpeace climbers abseiled down to the 8th floor of the building housing the French Embassy in Wellington to hang a big banner that asked, “Last Test Ever?”

It was to be the last French nuclear weapon test, but not the last nuclear test ever. Greenpeace Campaign Director Stephanie Mills warned at the time that military experts were saying the Chinese Government was expected to test more nuclear weapons, which could severely jeopardise progress on agreement at the UN Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty negotiations in Geneva, and even encourage other nations to carry out more nuclear tests.

Looking back, the presence of Greenpeace’s boats with the Pacific Peace Flotilla at Moruroa, and the mass mobilisation against the tests in Rarotonga and Papeete between June and October 1995 galvanised the global peace and environmental movements, and put massive pressure on the French Government to stop the planned tests.

One French writer commenting on the protests suggested that the Pacific Peace Flotilla had evoked the ‘spirit of Dunkirk’, like a small armada of yachts rallying to Greenpeace’s call to sail across the sea and join its defiance of the nuclear ‘jackboot’.

The original planned series of eight French nuclear tests ended early and was cut back to six. Most of the tests were relatively low yield, which meant the combined total yield (231 kilotons) was lower than in the previous years.

France and China sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty

A dozen Greenpeace activists protested at the Chinese Consulate in Auckland after the Chinese Government carried out a 50-kiloton nuclear weapon test at the remote Lop Nor nuclear test site in Xin Jiang on 8 June. The activists held an 11-metre banner painted with Chinese characters that read, ‘Stop Nuclear Testing – Now Start Disarming’ and two large posters of Chinese Prime Minister Li Peng that read, ‘Li Peng – Nuclear Proliferator’ and ‘Li Peng – Environmental Criminal’, plus two large Chinese flags with radiation symbols painted on them.

At the same time, MV Greenpeace was sailing to the port of Shanghai in China to protest against the Chinese Government’s latest nuclear weapons test. On 12 June, as the boat was heading toward an anchorage near the mouth of the Yangtze River, which leads to the port of Shanghai, four Chinese naval vessels surrounded MV Greenpeace and 70 uniformed military and customs officials boarded the boat, blocking it from continuing to the Port of Shanghai.

On 30 July, a team of six Greenpeace activists scaled the Chinese Embassy building in Wellington to hang a “Now Start Disarming” banner after the Chinese Government’s 45th – and last ever – nuclear weapon test at remote Lop Nor in Xin Jiang.

In addition to the fourth-floor banner, the activists also ran up a ‘Rad’ flag on the embassy’s flag pole – a red flag with a large yellow and black radiation hazard symbol in the top left corner instead of the five yellow stars of the Chinese flag. Another ten activists held up a second “Now Start Disarming” banner and more ‘Rad’ flags in front of the ground floor embassy entrance.

Speaking in front of the embassy entrance, Greenpeace Campaign Director Stephanie Mills called on the Chinese Government to end its nuclear weapons testing programme and sign a zero-threshold Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

Within months of the last test at Moruroa, French President Jacques Chirac announced that France would sign a zero-threshold Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) at the UN, which had been a central goal of Greenpeace’s nuclear testing campaign for 25 years, as well as the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.

France also dismantled its nuclear testing infrastructure at Moruroa and stopped production of highly enriched uranium for use in its nuclear warheads in 1996.

Soon after that, China followed France and announced that it had ended its nuclear testing programme and would agree to sign the CTBT. The CTBT was agreed at the UN General Assembly in New York, USA, in September 1996, which was 25 years after the first Greenpeace protest at Amchitka in Alaska USA, in September 1971.

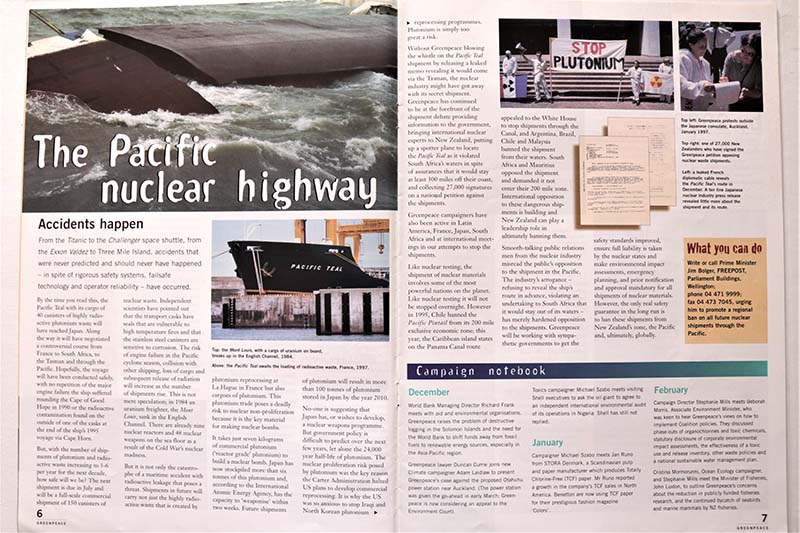

Plutonium shipments resume

Shortly after the last French nuclear test, another nuclear threat appeared on the horizon. News media reported that spent nuclear fuel from nuclear reactors and reprocessed Plutonium waste and mixed oxide shipments were to resume in 1997 between France, Britain, and Japan, and that the shipments could be routed through the Tasman Sea and the Pacific region, posing the risk of a nuclear accident.

The original Rainbow Warrior had first protested against Plutonium production at the Sellafield nuclear factory in the UK in 1978 and then at the French nuclear factory at Cap la Hague in coastal Brittany a few years later.

Nuclear shipments from those factories to Japan resumed in 1997, so Greenpeace’s Nuclear Campaign shifted its attention to campaigning against them during the late 1990s and the 2000s.

In January 1997 Greenpeace protested outside Japan’s Consulate in Auckland in opposition to a new Plutonium shipments travelling through the Tasman Sea and the Pacific Ocean en route from France to Fukushima in Japan, where the plutonium was to be stockpiled. Activists held a banner that read ‘Stop Plutonium’, French and Japanese flags with radiation symbols painted on them, and set off a loud siren.

Greenpeace also gathered 27,000 signatures in New Zealand on a hard copy petition opposing the shipments, urging the NZ Government to ban all future shipments from entering NZ’s 200-kilometre Exclusive Economic Zone, and demanding full liability from Japan in case an accident at sea contaminated NZ fisheries and coastlines.

“These shipments pose a potential environmental risk if one of the vessels sinks – as a similar one did in the English Channel in 1984 – and Plutonium leaks into the environment,” said Greenpeace New Zealand Campaign Director Stephanie Mills. “They also pose a risk of nuclear proliferation because Plutonium is the main material needed to make nuclear weapons and Japan has the capacity ‘weaponize’ Plutonium within two weeks, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency.”

SV Rainbow Warrior II also toured the South Pacific region In August-September 1997 to help raise awareness of the risks posed by the Plutonium shipments, discuss the issue with political leaders, and gather signatures on a hard copy petition opposing the shipments which was presented with a total of 40,000 signatures to Cook Islands Prime Minister Geoffrey Henry at the South Pacific Forum meeting in Rarotonga during a march in the capital, Avarua.

A few years later a new Nuclear-Free Tasman Flotilla was formed in 2001 led by SV Tiama in the tradition of the 1995 Pacific Peace Flotilla.

“The Nuclear-Free Tasman Flotilla in 2001 was Simon Boxer’s idea,” recalls SV Tiama skipper Henk Haazen.

The Nuclear-Free Tasman Flotilla comprised of three yachts departing from Australia: “SV Tiama“, “SV Fand” and “SV Antarctica”, and four yachts departing from New Zealand: “SV Ranui“, “SV Nanu“, “SV Secret Affair” and “SV Siome“.

They s쳮ded in finding and confronting the Plutonium shipments made through the Tasman Sea in 2001, and in 2002 they helped expose the fact that one of the military escort ships, the UK Royal Navy destroyer HMS Nottingham, had run aground off Lord Howe Island, en route from Japan to the UK.

“You have to seriously wonder if the people that made the decision to send this dangerous cargo through our region on a ship in the middle of winter know what they are doing. The shipment is dangerous enough on its own, let alone adding the risk of sending it through southern seas in winter,” said Greenpeace New Zealand Nuclear Campaigner Bunny McDiarmid.

The presence of the Nuclear-Free Tasman Flotilla helped keep the pressure on the shipping nations to deter them from using the Tasman/Pacific route.

Stopping US Star Wars missile tests

Another campaign push targeted the US Star Wars missile testing programme. Greenpeace first started its campaign against the US Star Wars missile tests at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands in June 1985 when the crew of the original Rainbow Warrior mounted a sea-based protest there.

Greenpeace’s protests continued at Kwajalein into the early 1990s with SV Rainbow Warrior II taking over from the original Rainbow Warrior, until the Star Wars military programme was eventually cancelled by the US federal government in October 1993.

Following a period with a Democratic Party majority in the US Senate during the presidency of Democrat Bill Clinton, the Republican Party gained a majority in the US Senate in 1998 and started to press for the US Star Wars missile testing programme to be resumed.

These developments prompted Greenpeace to renew its campaign against the Star Wars missile tests with major protest actions at the Kwajalein missile test site and the US Air Force Base at Vandenberg when the missile tests resumed in 2000 and 2001.

10 July 2000 – Washington Post article about Greenpeace disrupting a US Star Wars missile test at Kwajalein. Published 10 December 2001

Greenpeace New Zealand played an important role in the campaign, which brought together Kiwi ‘veterans’ of the various Rainbow Warrior campaigns at Moruroa, including Alice Leney, Henk Haazen, Bunny McDiarmid, Duncan Currie, and Stephanie Mills.

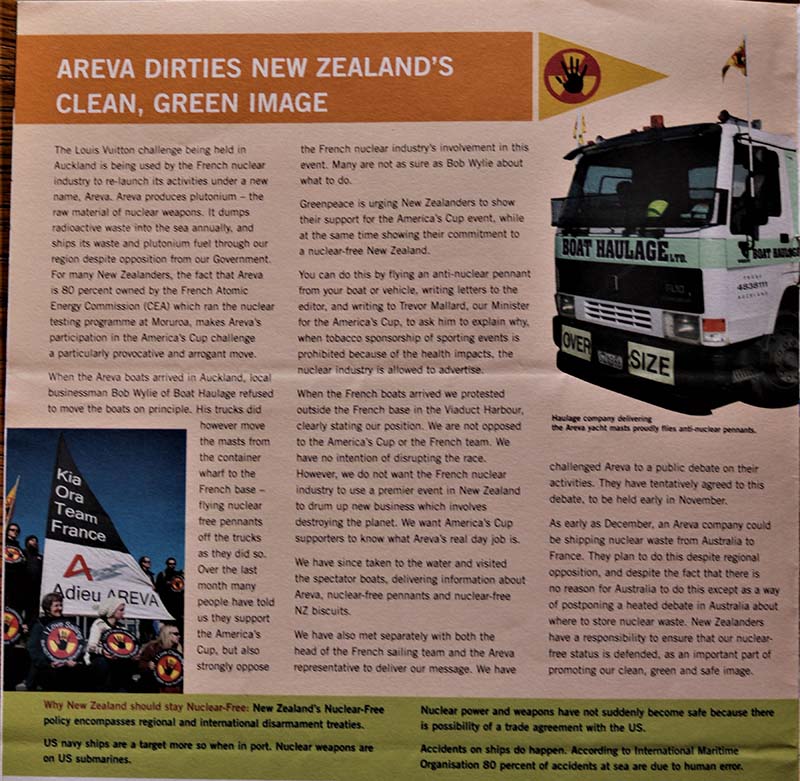

A French nuclear giant taints the America’s Cup

In 2002, the French nuclear giant ‘Areva’ announced that it planned to sponsor an America’s Cup team in the upcoming cup races to be held in New Zealand.

Once again, Greenpeace was prompted into action – in New Zealand and France – and a new Nuclear-Free Flotilla was formed around SV Tiama in 2003 to oppose the company’s participation in the race. The campaign opposed the company’s role in the production of Plutonium and radioactive pollution at the Cap La Hague nuclear factory in coastal France.

The Nuclear-Free Flotilla that followed the Areva-sponsored boat out to the racecourse in the Hauraki Gulf included SV Tiama, SV Ranui, SV Notredam, SV Sonshu, SV Legacy, SV Secret Affair, SV Arresto, SV Equinox, SV Waiaro, SV Blue Moon, SV Ethel, and a various individual kayakers.

This Flotilla included boats from the 1980s Auckland Peace Squadron, boats from the 1995 Pacific Peace Flotilla, boats from the 2002 Nuclear-Free Tasman Flotilla, as well as ordinary New Zealanders who wanted to let Areva know that while the French sailing team was welcome, French nuclear industry sponsors were not.

The Flotilla crews and protesters on board them ranged in age from 14 to 70-years-old, representing generations of New Zealanders unhappy with the French nuclear industry using the event to promote its polluting business.

“It’s a slap in the face for New Zealand that Areva is here as a nuclear sponsor in the America’s Cup when last year they were here backing a completely different boat – one that was shipping Plutonium through our region and which our Government strongly opposed,” said SV Tiama skipper Henk Haazen.

In the end, the Areva-sponsored boat did not get very far in the races and was out well before the final.

“President Mitterrand authorised Opération Satanique”

On 10 July 2005, the French daily newspaper Le Monde published extracts from a previously secret 1986 account written by Admiral Pierre Lacoste, former head of France’s DGSE foreign intelligence service, that revealed France’s late president Francois Mitterrand authorised the operation that resulted in the bombing of Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior in Auckland on 10 July 1985. The DGSE reportedly gave the bombing operation the code name, “Opération Satanique”.

Papers show Mitterrand approved Rainbow Warrior bombing”, Reuters, NZ Herald, 10 July 2005

“I asked the president if he gave me permission to put into action the neutralisation plan that I had studied on the request of Monsieur (Charles) Hernu,” Lacoste wrote. Hernu was French defence minister at the time. “He gave me his agreement while stressing the importance he placed on the nuclear tests. I didn’t go into greater detail on the plan as the authorisation was explicit enough,” he said.

Admiral Lacoste added that he, “would not have launched such an operation without the personal authorisation of the President of the Republic”. Admiral Lacoste’s account, dated 8 April 1986, was contained in a 23-page handwritten document that was previously secret.

Sir Geoffrey Palmer, who was NZ’s Deputy Prime Minister in 1985, was quoted by the NZ Herald as saying that Mitterrand’s role in the bombing had never been clear: “It is very disappointing because one would not expect the president of a friendly nation to authorise an illegal act against a nation with whom you enjoy friendly relations and with whom you have fought in two world wars. That seems to me to be extraordinary.”

Sir Geoffrey also reportedly said it was possible that Mitterrand didn’t know the extent of French Defence Minister Charles Hernu’s plans: “I dare say that what Mitterrand authorised was something pretty general, not something all that specific.” The NZ Herald also quoted Sir Geoffrey as saying that everyone involved in the bombing carried out by the French DGSE had an interest in protecting their reputations, but that Mitterrand, who died in 1996, was no longer around to comment on Admiral Lacoste’s account.

NZ Prime Minister Helen Clark (1999-2008) was also quoted by the NZ Herald as saying, “It confirms what we have always suspected was the case, that the attack on the Rainbow Warrior was authorised at the highest level.”

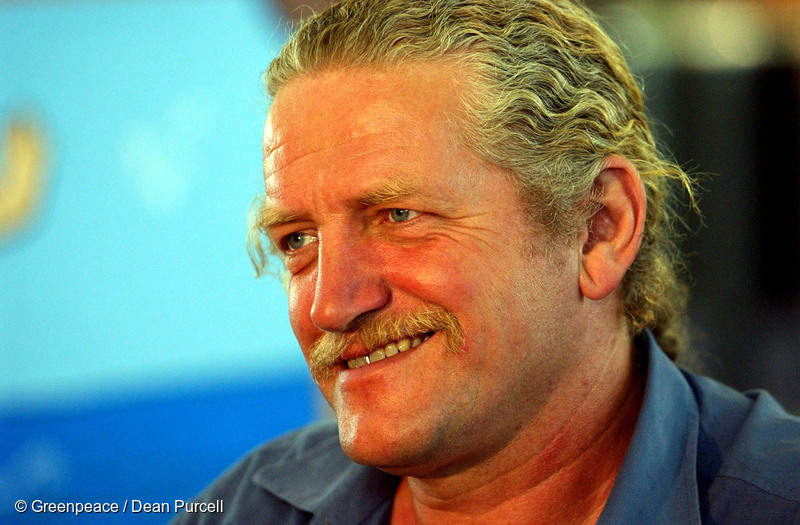

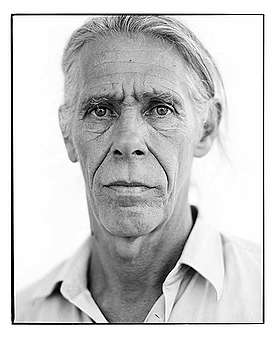

Former Greenpeace International Executive Director Steve Sawyer, who was on board the Rainbow Warrior when the first of two bombs planted by French DGSE agents exploded, said Le Monde’s report came as no surprise to him, although he found the timing of its release peculiar, coming as it did on the 20th anniversary of the bombing: “Mitterrand’s always been responsible for the Government. We’ve always held him responsible.”

Steve Sawyer also said that others had claimed that Mitterrand did not know about the plans to bomb the Greenpeace flagship, but never Mitterrand himself. “It doesn’t change anything. No one thought it was a rogue spy service acting against the [French] Government.”

“Greenpeace not surprised at Rainbow Warrior findings”, Ainsley Thomson and Agencies, 11 July 2005.

According to another account of ‘L’Affaire Greenpeace’, written in 2015 by French investigative reporter Edwy Plenel – the journalist who had uncovered the existence of the ‘third team’ of DGSE agents who planted the two bombs on the Rainbow Warrior in the 18 September 1985 edition of Le Monde – Plenel says that he discovered the existence of the ‘third team’ with the help of an informer within the French government of Laurent Fabius, who he called le Consul [the Consul].

(“La Troisième Équipe—Souvenirs de l’Affaire Greenpeace”, Edwy Plenel, Editions Don Quichotte, 2015)

“Rather than a straight informer, Plenel describes him more like a guide or a coach who puts him on the right tracks, and warns him when he makes a wrong turn – very much like the ‘deep throat’ source used by Bob Woodward and Carl Berstein at The Washington Post during Watergate,” according to former Greenpeace International Political Director Remi Parmentier.

After several decades in global leadership roles within Greenpeace USA and Greenpeace International, Steve Sawyer left in 2007 to continue his work on climate change. He co-founded the Global Wind Energy Council to promote renewable wind energy and provide a representative forum for the entire wind energy sector at an international level. He led the organisation as its General Secretary for ten years.

During that time, global wind energy installations grew from 74 gigawatts to 539 gigawatts to become one of the world’s most important energy sources, and he made a significant contribution to the development of wind energy in India, China, Brazil, and South Africa.

Steve was diagnosed with lung cancer in April 2019 and died on 31 July 2019 in Amsterdam. He had been one of Greenpeace’s most important global leaders. During the decades he helped to lead Greenpeace he was a strong advocate for the organisation’s nuclear, Antarctica, and climate change campaign work, and a good friend to Greenpeace New Zealand and Greenpeace Pacific.

Steve Sawyer, 1956-2019, Brian Fitzgerald, 1 August 2019

France honours DGSE agent who spied on Greenpeace

In July 2017 the French DGSE undercover spy Christine Cabon, who infiltrated the Greenpeace New Zealand office in 1985 as a spy to find out when the Rainbow Warrior would be arriving in Auckland prior to the planned bombing of the ship by the French DGSE, was located in rural France.

She had used the false name ‘Frederique Bonlieu’ to gather information about when and where the Rainbow Warrior would be moored in Auckland for the DGSE bombing team that arrived later and carried out the fatal attack, which killed Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira.

New details were reported in an article by Cecile Meier and Kelly Dennett in the Sunday Star Times about Cabon’s role in preparing the way for the DGSE bombing team, and about her background as an officer in the French DGSE and her family background, including a father and brother who served in the French military.

After her cover was blown and an Interpol arrest warrant was issued for her, she was no longer able to work for the DGSE and went into the French military where she was decorated with the highest honour of the French State, the Legion D’Honneur.

The article also reported that Cabon was unrepentant about the Rainbow Warrior bombing and the death of Fernando Pereira.

‘No War for Oil’

Greenpeace also campaigned against the war in the Persian Gulf in 1990/91 and again in 2003, using the slogan ‘No War for Oil’. Greenpeace said that both the wars raised issues around the deployment and use of nuclear weapons in wartime, and the environmental impacts of war itself, especially after the massive oil spills and oil fires that occurred during the 1990/91 Gulf War.

UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

Most recently Greenpeace welcomed news that a new UN treaty banning nuclear weapons was ratified by 50 countries in October 2020.

The treaty bans the production, use, and stockpiling of nuclear weapons from January 2021, although the five declared nuclear weapons states have not yet signed it.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres described the treaty as “the culmination of a worldwide movement to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons … It represents a meaningful commitment towards the total elimination of nuclear weapons, which remains the highest disarmament priority of the United Nations.”

Looking back to Greenpeace’s origins in 1971, nuclear weapons testing has ended, a zero-threshold CTB Treaty has been agreed, and a new treaty makes nuclear weapons illegal. The number of nuclear weapons in the world has also been reduced from over 50,000 at the end of the Cold War in 1990 to about 11,000 today.

Militarisation and nuclearisation of space

The new frontiers of the arms race are now the deployment of weapons in space and the spread of nuclear propulsion into space, both of which risk environmental catastrophe. The militarisation of space also threatens new forms of nuclear war-fighting with the development of rapidly deployable nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered cruise missiles such as the Russian 9M730 ‘Skyfall’, which some experts are now calling a ‘flying Chernobyl’.

In March 1991, Greenpeace Missile Flight Test Ban Campaigner Martini Gotje had visited Washington DC to meet with the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). At the time, both Greenpeace and FAS were publicly opposed to a proposed US military nuclear-powered rocket engine code-named ‘Project Timber Wind’ being flight-tested over New Zealand and Antarctica.

A test flight of ‘Project Timber Wind’ over the southern hemisphere would have breached the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone Treaty and potentially New Zealand’s Nuclear-Free legislation, and the Antarctic Treaty. Six months later ‘Project Timber Wind’ was cancelled by the US Deputy Secretary of Defense.

Martini Gotje is one of Greenpeace’s longest-serving activists and campaigners, whose involvement spans sailing on the first voyage to Moruroa Atoll on board SV Fri in 1973, the Rainbow Warrior’s voyage across the Pacific to New Zealand in 1985, and multiple voyages on SV Rainbow Warrior II and SV Vega in the Pacific in the 1990s, through to today.

Twenty-eight years after ‘Project Timber Wind’ was cancelled, in May 2019 the US House Appropriations Committee approved an obscure item which included funding of $125 million for nuclear thermal propulsion (nuclear-powered rocket engine) development, including planning for a “flight demonstration by 2024”.

This effectively resurrected “Project Timber Wind”, which had originally been intended to carry large military payloads into orbit and would have enabled the militarisation of space as part of the US Star Wars weapons programme. Doing so would undermine the important Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty that the US signed with the Soviet Union in 1972.

Following that in December 2019, then-US President Donald Trump announced the establishment of a new US military “Space Force”. This represented another dangerous step in the militarisation of space that further undermined the 1972 ABM Treaty, which was intended to limit such developments.