Oceans campaign

An ecosystem approach

New Zealand has been on the frontline of Greenpeace’s global Oceans Campaign since the 1980s. New Zealand’s threatened dolphin, sea lion, seabird, shark, and tuna species are all impacted by destructive commercial fisheries operating within the NZ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and many commercially fished species are impacted by overfishing.

Since the early 1990s Greenpeace’s Oceans Campaign has also had an emphasis on taking an ecosystem approach and a precautionary approach to the marine environment and fisheries management. That’s part of the reason why in 2020 Greenpeace called for 30% of the world’s oceans and marine habitats within them to be fully protected from commercial fishing and minerals exploitation.

Over the past three decades Greenpeace’s Oceans Campaign has also championed protection of our iconic marine species such as whales, dolphins, sea lions, albatrosses, sharks and tunas to help achieve protection of their breeding grounds and habitats in New Zealand, as well as the wider Pacific and Southern Ocean regions.

The campaign has also targeted specific destructive fishing methods and the flawed NZ Quota Management System (QMS) – which has allowed successive ministers to set some unsustainable quotas – and the increasing threat from plastic pollution to ocean ecosystems.

Pulling the plug on plastic pollution

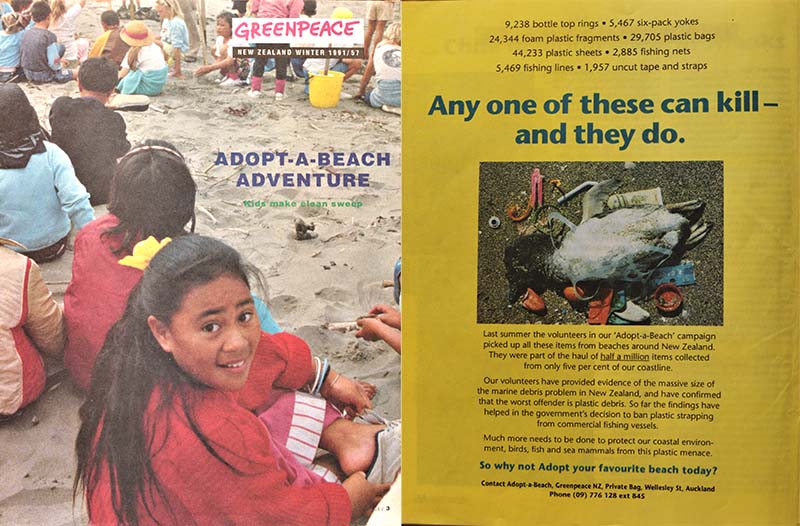

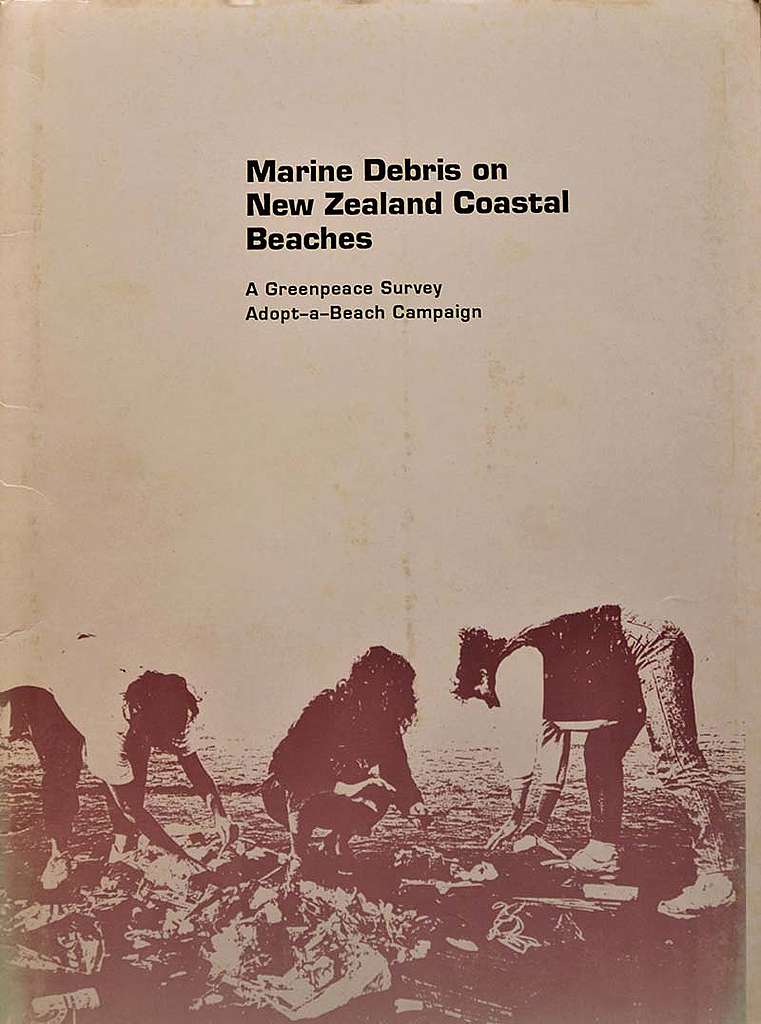

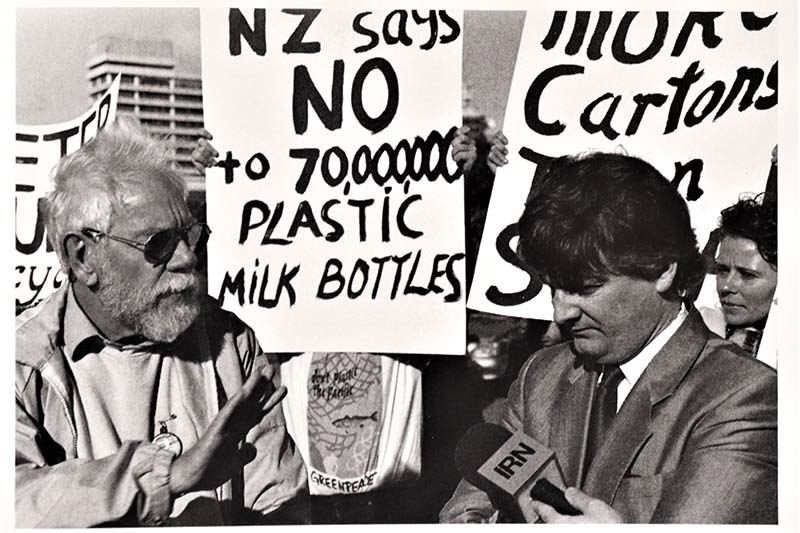

In May 1990, Greenpeace published a new report compiled by recently retired Auckland University Engineering Lecturer Peter Smith who was a long-time volunteer for Greenpeace, on the extent of plastic pollution on NZ beaches and called for a range of new government policies to combat the rising tide of plastic pollution.

It detailed the huge amounts of plastic collected by thousands of school children and volunteers as part of Greenpeace’s Adopt-a-Beach project, which had been launched in October 1989. Project participants carried out a total of 338 beach clean-ups and recorded over 200,000 items of mostly plastic pollution. But that was only the tip of the iceberg as it did not include all NZ beaches.

The results of the project were delivered to Environment Minister Peter Dunne by Peter Smith with a demand that the Government regulate to combat the rising tide of plastic waste and ensure effective recycling systems.

Saving our Sea Lions

Later in 1990, Greenpeace proposed a new Marine Mammal Sanctuary out to 100-km around NZ’s Subantarctic Auckland Islands to protect endangered New Zealand Sea Lions that were being drowned in the Arrow Squid trawl fishery that operated in the area.

The proposal passed unanimously at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) General Assembly, but a few months later in 1991 the newly-elected National Government announced that it would only set up a smaller sanctuary that went out 12 nautical miles offshore, and would create an annual NZ Sea Lion ‘kill quota’. That meant the Arrow Squid fishery would be legally allowed to kill up to a specified number of NZ Sea Lions in the area around the sanctuary every year, that would be set by the Government.

Confronting overfishing

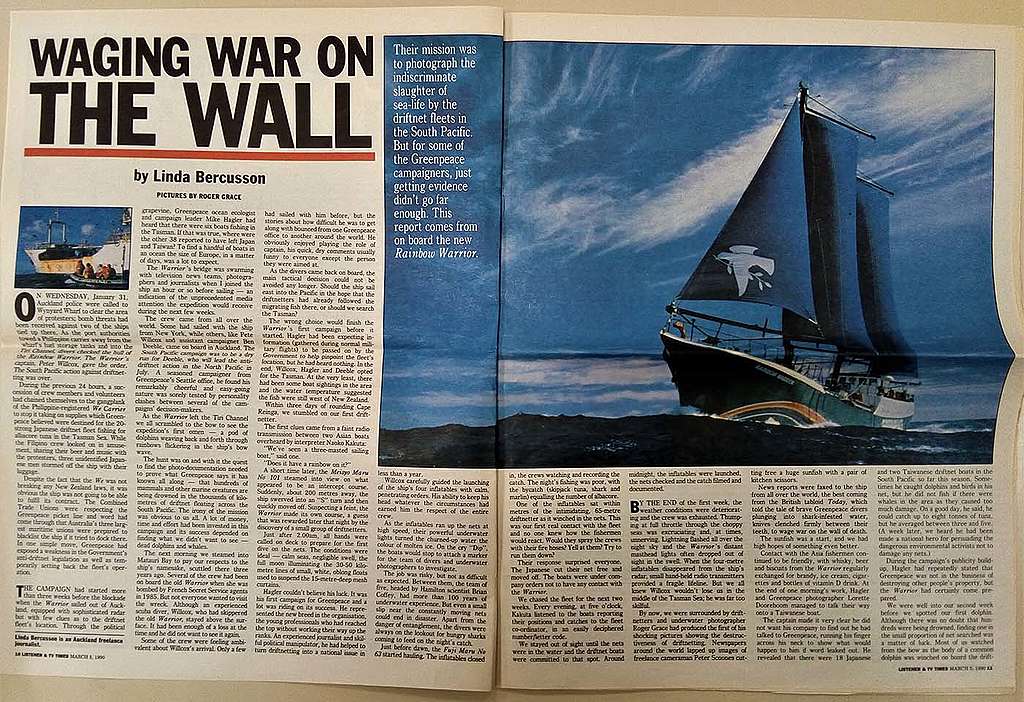

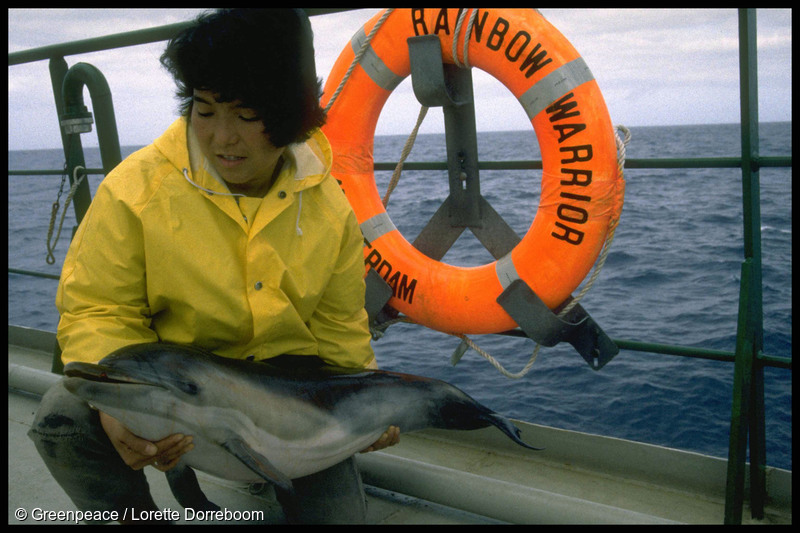

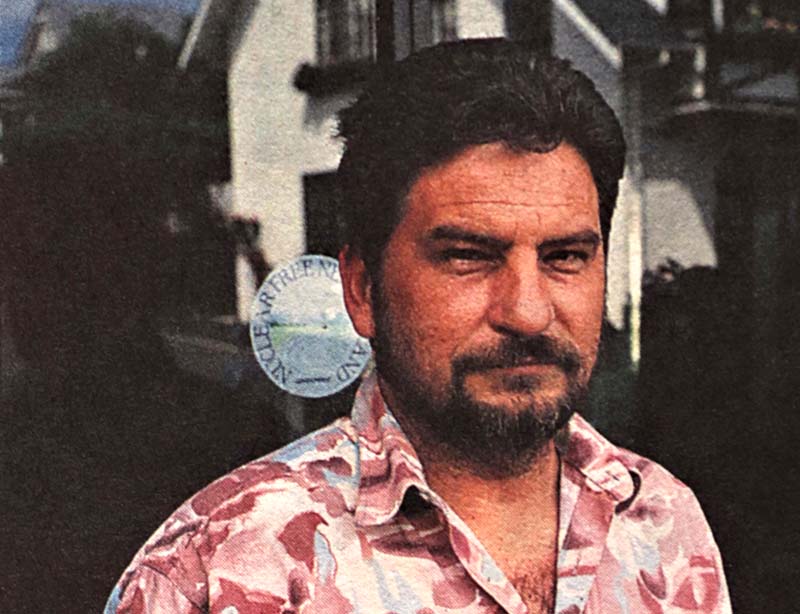

Greenpeace’s new flagship SV Rainbow Warrior II embarked on an expedition to expose the indiscriminate destructive impact of large-scale ‘Wall of Death’ driftnet fishing on marine wildlife in the Tasman Sea in January 1990, with the goal of documenting the practice and campaigning for a ban. The expedition was instigated and organised by Greenpace New Zealand Oceans Campaigner Mike Hagler.

During the expedition New Zealand underwater photographer and marine biologist Dr Roger Grace and Lorette Dorreboom photographed the appalling death toll of dolphins, marine turtles, and large fish killed by the driftnets.

His powerful photos of the destruction of marine life caused by the driftnets were sent to news media around the world via the ship’s photo-fax and onboard campaigner Mike Hagler spoke to journalists via satellite phone. The powerful images were widely published in global news media, including in New Zealand, and footage distributed after the boat returned to port also ran on TV news reports. This ensured the campaign received mass coverage in the world’s news media.

Mike Hagler attended the UN General Assembly in New York with NZ Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer in September 1990 to promote a proposal for a global ban on driftnet fishing on the high seas.

“Soon after I started working for Greenpeace, I arranged to meet Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer to explain to him the impact of large-scale driftnets on marine wildlife and tuna stocks,” recalls Mike Hagler, who was Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner at the time. “After my pitch he said to me that he had no idea of the level of destruction that it was causing and that his officials hadn’t stressed it to him. Then he said, ‘what you’ve told me has completely changed my mind and I am going to tell my officials to do something about this’.”

“A little later he called and asked me to accompany and support him at the annual UN General Assembly (UNGA) in New York, and discuss ways of working to tackle the driftnets issue. When I got to New York, I met with the relevant UN staff and various delegations and I visited the US UNGA office. When I arrived, they said, ‘Mike Hagler, it’s so good to meet you. We followed your [January 1990] campaign in the Tasman Sea and we’re backing you 100% and will propose a resolution for a driftnet ban on the High Seas at the UNGA’.”

“I was amazed,” says Mike Hagler.

That led to a new UNGA resolution in 1991, and then in 1992 the UNGA voted to ban the use of all driftnets longer than 2.5 km on the high seas.

Greenpeace then turned its attention to overfishing in NZ Orange Roughy bottom trawl fisheries. In 1993, Greenpeace New Zealand Executive Director Cindy Kiro gave the go-ahead to filing a request in the NZ High Court for a judicial review of the Minister of Fisheries’ 1993/94 Orange Roughy Chatham Rise quota decision.

The legal action sought to stop the Minister from continuing to set the Orange Roughy quota many times above safe levels, risking the collapse of the fishery, and ignoring warnings from fisheries scientists that Orange Roughy – one of NZ’s most valuable fisheries – was in danger of being fished out.

The case, which was prepared by Duncan Currie, Mike Hagler, and Leith Duncan, took more than a year to be heard. Just a few months after Greenpeace’s legal papers were filed in the High Court, the NZ Fisheries Minister cut the annual Chatham Rise Orange Roughy quota by nearly half, vindicating Greenpeace New Zealand’s legal action.

Greenpeace cautiously welcomed the court’s subsequent 1995 ruling on the case.

Greenpeace had argued that the industry’s flawed ‘fish now, conserve later’ argument was not legal, and that the Minister was legally required to give effect to the Fisheries Act and should follow scientific advice and take a precautionary approach in the face of any uncertainty.

“That case was a good example of strategic litigation,” recalls Greenpeace Legal Counsel Duncan Currie. “Up to that point, the NZ Minister of Fisheries was under pressure from the fishing industry and its lawyers to make decisions that favoured the industry.”

Greenpeace continued its campaign for better management of NZ fisheries through the 1990s into the 2000s, but despite the 1995 ruling successive NZ fisheries ministers continued to set unsustainable quotas in some of the most lucrative NZ fisheries.

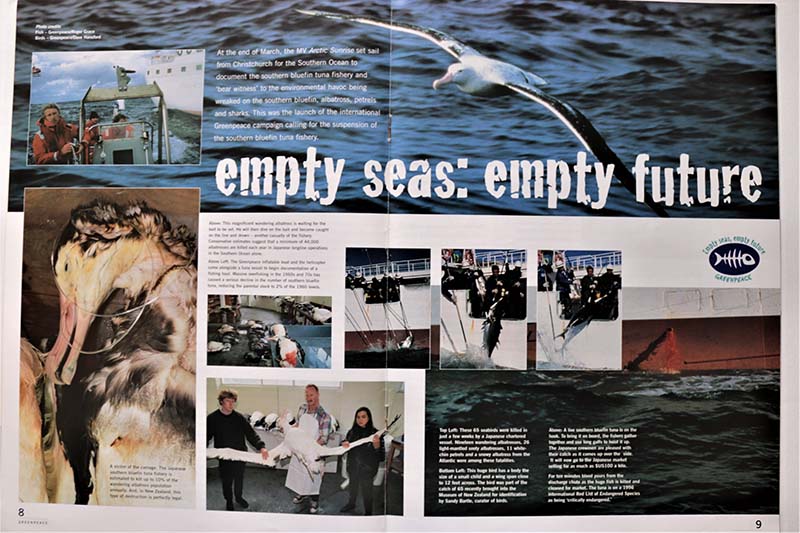

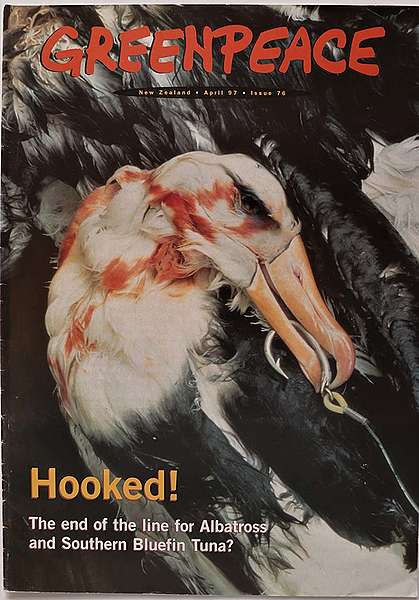

In 1996, led by new Oceans Campaigner Cristina Mormorunni, the Oceans Campaign began to target seabird bycatch in the Southern Bluefin Tuna longline fishery, which was killing huge numbers of non-target species including threatened species of albatross and shark, as well as Southern Bluefin Tuna, which was itself becoming critically endangered due to overfishing.

The common theme in the mismanagement of these highly valuable NZ fisheries was that overfishing was being driven by the pursuit of short-term profit at the cost of collapsing fish stocks and long-term sustainability.

They were also killing non-target species. The Orange Roughy bottom trawl fishery was destroying ancient corals on seamounts with huge heavy trawl gear, the Hoki trawl fishery was drowning NZ Fur Seals in its nets, and the Southern Bluefin Tuna fishery was killing albatrosses and sharks by catching them on baited longline hooks.

Longline killers

In 1997, Greenpeace sent its new ice-class ship MV Arctic Sunrise into New Zealand Subantarctic waters to document the unsustainable nature of the NZ Southern Bluefin Tuna fishery there. The helicopter on board enabled Greenpeace to locate and follow three Japanese longlining charter vessels fishing for Southern Bluefin Tuna and photograph the huge fish being gaffed alive while they were being hauled aboard, as well as the deadly toll taken on seabirds and sharks. Scientists had estimated that 44,000 albatrosses were being killed in Japanese longlining operations in the Southern Ocean every year at the time.

The expedition, organised by Cristina Mormorunni and Rob Taylor, also marked the start of a global campaign calling for the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna to suspend fishing for the species in its South Pacific range. Not only were global Southern Bluefin Tuna fisheries killing non-target seabirds and sharks, but they had also reduced the adult population of the tuna to just 2% of 1960 levels.

In June 1999 Greenpeace urged the NZ Government to nominate Southern Bluefin Tuna under the Convention for the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in order to stop exports of it to Japan.

“If New Zealand is serious about protecting this critically endangered species, immediate action should be taken to nominate it under CITES. This would make trade in Southern Bluefin Tuna illegal between other fishing nations such as Taiwan, South Korea and Indonesia, and Japan, where 95% of the global catch is sent,” said new Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Sarah Duthie.

More marine reserves

New Zealand’s endemic endangered Hector’s Dolphin and critically endangered Maui Dolphin were also being killed as ‘bycatch’ in coastal fishing nets. Greenpeace staff and SV Rainbow Warrior II crew helped carry out at-sea surveys of Hector’s Dolphins and Maui Dolphins in the 1990s and again in the 2010s. Greenpeace called for the Banks Peninsula Marine Mammal Sanctuary to be extended to better protect Hector’s Dolphin habitat, and for increased protections including a ban on set nets, gill nets, and inshore trawling in Maui Dolphin habitat out to the 100-metre depth contour along the east coast of the North Island.

Greenpeace also campaigned for the creation of no-take marine reserves in coastal areas to protect all marine life within them, and more marine mammal and ocean sanctuaries in and around New Zealand and in the Southern Ocean.

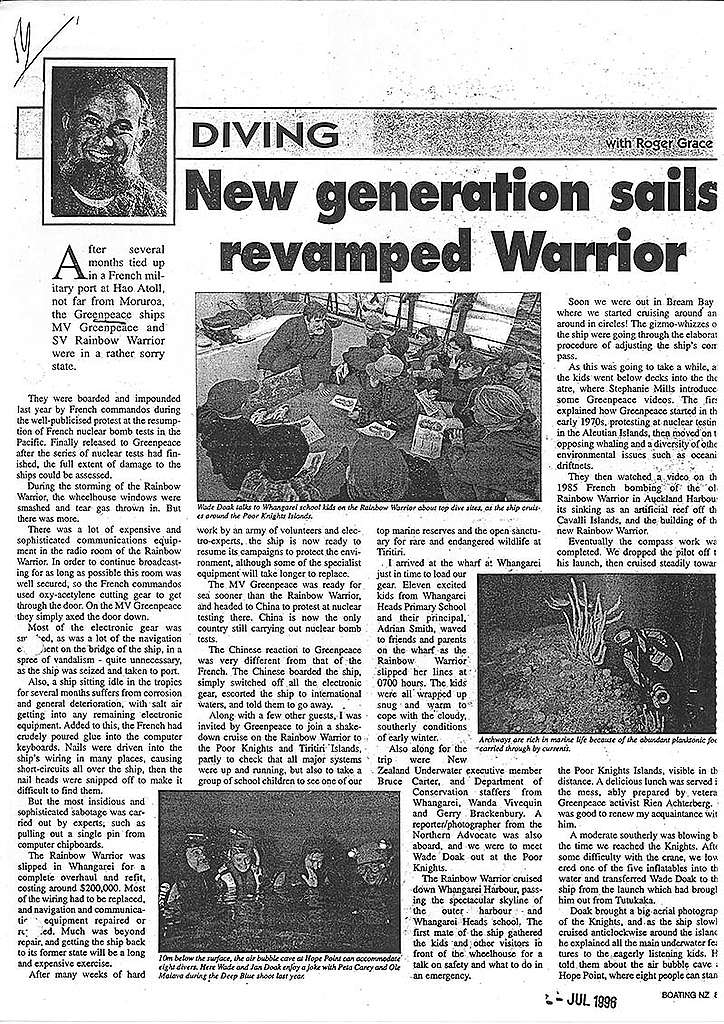

SV Rainbow Warrior II sailed to the Poor Knights Islands in June 1996 when Greenpeace was working with former Greenpeace Rainforests Campaigner Jacqui Barrington, marine conservationist Wade Doak, and marine biologist Dr Roger Grace to campaign for the Government to fully protect the waters around the islands from fishing and create a 12-nautical mile oil tanker exclusion zone around them.

The following year, the National-led Coalition Government fully protected the waters 800-metres out from the islands from all fishing, but chose not to establish an oil tanker exclusion zone.

Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary

During the 1990s, Greenpeace also championed the creation of a 50 million square kilometre Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary around the Antarctic continent and launched a series of anti-whaling expeditions into the Southern Ocean to expose and confront the Japanese Government’s bogus ‘scientific’ whaling fleet operating there.

The Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary was declared by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1994 but the Japanese Government continued its whaling operations in the Southern Ocean falsely claiming it was ‘scientific’, when in fact the whale meat from the hunt there was then shipped back to Japan to be sold in restaurants there.

Greenpeace kept up the pressure on the Japanese Government to stop whaling in the Southern Ocean by organising protests at Japanese consulates and embassies around the world, including in New Zealand, and continuing to send its ice-class ships MV Arctic Sunrise and MV Esperanza on annual expeditions to the Sanctuary to confront and disrupt the Japanese Government’s annual whale hunt there in the 1990s and 2000s. Greenpeace New Zealand was closely involved in that campaign through the work of oceans campaigners Sarah Duthie (2000-2004), Pia Mancia (2005-06), and Karli Thomas (2008-2016).

Over the years these expeditions saved thousands of whales from being killed. Memorably, in January 2008, Greenpeace’s ice-class ship MV Esperanza chased the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet out of the hunting grounds after a high-speed pursuit over hundreds of kilometres through fog and rough seas.

After confronting the whaling fleet close to the ice edge, MV Esperanza pursued the factory ship Nisshin Maru over the 60 degrees latitude mark, the boundary of the whale hunting grounds, followed by the whale catcher vessel Yushin Maru.

“We came here to stop the fleet from whaling and we have done that. Now they are out of the hunting grounds they should stay out,” said Greenpeace Japan Campaigner Sakyo Noda. “We suspect that the fleet is now planning to re-fuel and offload whale meat that has already been processed onto the Panamanian-registered tanker Oriental Bluebird, a ship that had not been licensed to be part of the whaling fleet.”

“They are re-supplying a fleet that is not welcome in Antarctica and trafficking whale meat that is not wanted in Japan,” said expedition leader Karli Thomas. “In addition, we have seen the Oriental Bluebird re-fuelling the whaling fleet within the Antarctic waters in the past, which is a major threat to the pristine environment. The tanker is not registered as part of the whaling fleet, so should not be here.”

This one was Greenpeace’s ninth expedition to the Southern Ocean to defend the whales.

After decades of strong NZ government opposition to whaling, John Key’s National-led Government broke ranks to support a 2010 Japanese bid at the annual International Whaling Commission meeting to resume commercial whaling. Greenpeace responded by calling out the Key Government for selling-out the long-standing strong opposition of New Zealanders to whaling interests.

In 2014 the International Court of Justice court voted overwhelmingly that the size and scope of the Japanese Government’s so-called “scientific whaling” programme was not driven by scientific considerations, and that therefore all its permits must be cancelled and no new ones issued.

In March 2016, Greenpeace organised a mock ‘weigh-in’ of a six-metre replica whale ‘caught’ by John Key in front of his electorate office and called on him to reject any IWC deal that would legitimise a resumption of commercial whaling, which is what the Japanese Government had been calling for.

The Japanese Government whaling programme ends

Most recently, in December 2018, the Japanese Government announced it would end its whaling programme in the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary and officially withdraw from the IWC. While the end of whaling in the Sanctuary was welcome news, Greenpeace condemned the Japanese Government’s stated intention to then resume commercial whaling within its own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

Defending the deep from bottom trawling

Greenpeace’s Southern Bluefin Tuna and Orange Roughy campaigns expanded in the 2000s to target other bottom trawl fisheries in NZ and out into the wider Pacific region, sending MV Arctic Sunrise and SV Rainbow Warrior II to expose and confront bottom trawlers, tuna overfishing, and pirate fishing.

In 2004, SV Rainbow Warrior II documented the destructive impact of NZ bottom trawling in the Tasman Sea, including on endangered black coral that had been broken off, brought to the surface, and discarded by a bottom trawler.

Greenpeace also took action against a destructive bottom trawling vessel on the first day of talks at the United Nations General Assembly in New York in 2004 on how to better manage the planet’s oceans.

SV Rainbow Warrior II‘s crew used inflatable boats to disrupt the NZ bottom trawler, Ocean Reward, to stop it destroying deep-sea life while fishing in international waters in the Tasman Sea. They delayed the fishing vessel from deploying its trawl net by attaching an inflatable life-raft to it, running the gauntlet of being shot at with compressed air guns and sprayed with high pressure fire hoses by the Ocean Reward’s crew.

“We have documented the destruction caused by bottom trawlers, including New Zealand vessels on the high seas. Bottom trawling is a global problem and it needs a global solution. A United Nations moratorium is the only option that will ensure the immediate protection of deep sea life,” said Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Carmen Gravatt.

Greenpeace was able to publish photographic and video footage evidence of the destruction caused by bottom trawling, contradicting the NZ Amaltal fishing company’s director Andrew Talley’s claim that Greenpeace’s assertions about the impacts of bottom trawling were, “unsubstantiated claptrap”.

After the sustained campaign against bottom trawling by Greenpeace and its allies in The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, including Forest and Bird, ECO, and WWF, the NZ Government announced the closure of 32% of the NZ EEZ to bottom trawling in 2007. However, a Greenpeace analysis showed that these closures did little to stop the destruction of vulnerable deep-sea life threatened by bottom trawling and it was branded a ‘Clayton’s closure’.

Greenpeace released a composite map that showed where the fishing industry had been bottom trawling, overlaid with the fishing industry’s map of its proposed closures. The area to be closed was nowhere near the science-based protection that was needed.

Later in 2007, when the Minister of Fisheries again cut the annual Orange Roughy and Hoki quotas, Greenpeace warned that wider fisheries closures and more effective management measures would still be needed to safeguard fish stocks and marine habitats in the long-term.

For over a decade after the 1995 High Court ruling, Greenpeace said it was clear that the Ministry of Fisheries and the NZ Quota Management System was still failing to stem the decline in New Zealand’s two biggest fisheries.

Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Carmen Gravatt pointed out that the state of collapse of the Orange Roughy fishery brought into serious question the sustainability of the entire Orange Roughy population around New Zealand, and that there was also a risk of the complete collapse of the Hoki fishery in the near future.

Greenpeace launched a ‘Red List’ guide in 2018 listing the 12 most ‘at-risk’ commercially fished species, including Orange Roughy, Hoki, Southern Bluefin Tuna, Arrow Squid, and Antarctic Toothfish. The guide was compiled as part of a global campaign targeting supermarkets, urging them to remove unsustainably fished species such as Orange Roughy from their shelves. It also gave consumers guidance on which commercially-caught NZ species to avoid at supermarkets and in Fish and Chip shops.

The next year Greenpeace activists stopped a fishing vessel that planned to target Orange Roughy from leaving Auckland’s Waitemata Harbour and called on the Foodtown supermarket chain to stop selling Orange Roughy and instead implement a sustainable seafood policy.

The 45-metre Seamount Explorer was blockaded by Greenpeace activists in life rafts who locked themselves to a chain encircling the fishing vessel and held up banners reading, “Foodtown – costing us our oceans”. The fishermen onboard responded by turning high-pressure water hoses on the activists.

Greenpeace activists also hung a large banner on a downtown Auckland Foodtown supermarket and called on the company to implement a sustainable seafood policy and remove bottom-trawled fish species such as Orange Roughy, from its shelves.

Changing Tuna

In the South Pacific, a new Greenpeace tuna campaign exposed how migratory tuna stocks were increasingly being targeted in unregulated international waters by large fishing fleets from outside the region, including illegal ‘pirate’ fishing operations. Using its ships, Greenpeace was able to document the use of destructive fishing methods and devices.

In 2009 activists from Greenpeace’s MV Esperanza unfurled banners reading “Marine Reserves Now” and ”No Return from Overfishing” after it located a Japanese purse-seiner, Fukuichi Maru, scooping up tuna in a pocket of international waters in the Pacific where key tuna stocks were threatened with collapse.

The Fukuichi Maru was caught using a Fish Aggregating Device (FAD), something that was officially banned from use in the Pacific Ocean during August-September each year. It was clear, said Greenpeace, that there was a gaping loophole in the ban that allowed fishing fleets from Japan, the Philippines, and New Zealand to continue plundering tuna in the Pacific, including with the use of FADs.

“Countries are making a mockery of the two-month ban on FAD fishing. In our first week on the high seas, we came across six of these devices although they are banned,” said Greenpeace New Zealand Oceans Campaigner Karli Thomas from onboard MV Esperanza. “A total ban on the use of FADs is urgently needed. If Pacific tuna species are not protected soon, it will spell not just the end of Japan’s favourite sushi, but of a vital resource of Pacific Island countries.”

Greenpeace also renewed its earlier call for the closure of the Southern Bluefin Tuna fishery the following year and demanded the withdrawal of a plan to increase New Zealand’s quota by 27% when stocks were at an historic low point.

“Southern Bluefin Tuna Stocks are down to 4.6% and now New Zealand has just upped its quota by 27%. We are talking about a species that’s in as much strife as Maui Dolphin and Kakapo,” said Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Karli Thomas.

The Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna subsequently cut the total annual quota by 20% for the 2010/2011 fishing seasons, which Greenpeace described as a half-hearted attempt to halt the decline of a species in a fishery that should already have been classified as collapsed.

At the same time, Greenpeace also called on the NZ Government to stop all fishing for Orange Roughy after three major international retailers pulled the species from sale on their shelves due to sustainability concerns raised by consumers. Instead, the NZ Ministry of Fisheries proposed to reopen one of three previously closed Orange Roughy stocks that had not been fished since 2000 – when overfishing had driven it to collapse – and to also increase the annual Hoki catch.

As part of the campaign’s push to protect regional migratory tuna stocks in 2010, Greenpeace called on New Zealand canned tuna brands such as Sealord to follow the lead of overseas canned tuna sellers and to stop sourcing fish caught using methods which also killed marine turtles and sharks.

Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Karli Thomas said that tuna stocks and other ocean life were threatened by the fishing methods being used to fill Sealord’s tuna cans, and the campaign released online a new video calling on Sealord to ‘change its tuna’.

This was followed a few months later by the launch of an outdoor subvertising campaign in Auckland exposing Sealord’s sale of tuna caught using destructive fishing methods. Greenpeace volunteers deployed hundreds of posters and banners along main routes into and throughout the city centre. The posters featured the newly unveiled Sealord logo along with the words, ‘Nice Logo, Bad* Tuna* – Sealord’s canned tuna is caught unsustainably.’

In November 2011 activists from Greenpeace’s MV Esperanza protested against tuna vessels it had caught operating illegally in an area of international waters known as the ‘Pacific Commons’ near Indonesia. They filmed an unnamed purse-seine fishing vessel illegally trans-shipping its tuna catch to the carrier vessel, Lapu.

Six months later Greenpeace marked World Oceans Day by presenting its first-ever tuna sustainability awards to two New Zealand brands to recognise that both companies had introduced more sustainably caught canned tuna products over the previous year.

In May 2013, Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Karli Thomas welcomed news that Sealord would phase-out by 2014 its use of a destructive tuna fishing method that also killed non-target sharks, turtles, and juvenile tuna after Greenpeace’s campaign targeted the company, describing the news as another important step towards protecting the marine environment and halting the decline of Pacific tuna stocks, the main source of canned tuna sold in New Zealand.

With the entire population down to around just 60 individual Maui Dolphins in 2012, Greenpeace also called for an immediate and extended ban on gillnets, set nets, and trawling – the main threats to Maui Dolphin – throughout the species’ habitat along the west coast of the North Island from Maunganui Bluff to Whanganui, extending out to the 100 metre depth contour.

Antarctic Ocean Sanctuaries

Greenpeace also launched a new global campaign for the establishment of a 1.5 million square kilometre Ross Sea Ocean Sanctuary off Antarctica in 2012. At the time, John Key’s National-led Coalition Government chose not to support the proposal, but it was subsequently approved with the support of 24 countries at the annual meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) in November 2016.

Greenpeace joined with the other members of the New Zealand Shark Alliance in 2014 to welcome new laws banning shark finning in NZ waters.

“This is great news for the tens of thousands of Kiwis who have been calling for a ban on shark finning,” said Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner and New Zealand Shark Alliance spokesperson Karli Thomas. “However, thousands of Blue Sharks, which are the species most often caught just for their fins in New Zealand waters, may be killed just for their fins before the law is in place. Most Blue Sharks are caught as bycatch and pulled into the boats alive. Many could be released unharmed. To continue finning Blue Sharks is a senseless waste and there are no excuses for a delay of almost three years.”

Greenpeace activists shut down cat food giant Whiskas’ operations in Whanganui in May 2016 after its parent-company – Mars – confirmed that it sourced tuna from Thai Union, a seafood company that had been connected to slavery and destructive fishing methods. A few months later, Mars agreed to adopt a strong new action plan to clean-up its tuna supply chain.

In 2016 a new academic report ‘Reconstruction of Marine Fisheries Catches for New Zealand 1950-2010’ found the quantity of fish caught in New Zealand was more than twice that officially recorded. The University of Auckland report also released evidence that suggested the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) had been deliberately suppressing the information. The greatest proportion of the previously unaccounted-for sea life was made up of unreported industrial catch and fish discards dumped by commercial fishing operators. In response, Greenpeace called for an independent investigation of MPI.

“This is explosive. It looks like the ministry charged with looking after our oceans, have instead been looking after the fishing industry – it’s completely shocking. New Zealand’s industrial fishing companies have been underreporting the number of fish they have been taking for years, and the evidence suggests the MPI has been covering for them,” said Greenpeace Executive Director Dr Russel Norman.

Greenpeace continued to push the world’s largest tuna company, Thai Union, to change its business practices to protect seafood workers, reduce destructive fishing practices, and increase support for more sustainable fishing. In July 2017, after a two-year campaign, the work of hundreds of thousands of people was rewarded when the Thai Union company finally agreed to clean-up their supply chain and to crack down on human rights and labour abuse violations on its vessels.

Greenpeace also exposed widespread illegal fish dumping in the inshore NZ fishery in 2017 and unreported drownings of Hector’s Dolphins in set nets, and forced the Government to accept the need for surveillance cameras to be installed on fishing boats to monitor the accuracy of catch and by-catch reporting.

Ban the Bottle – Ban the Bag

Greenpeace welcomed a September 2017 Government announcement that it would establish a bottle refund scheme and urged them to follow it swiftly with a ban on plastic bottles because prevention is the best way to avoid plastic pollution.

Greenpeace sent MV Esperanza on an expedition to Antarctica in 2018 where it uncovered shocking levels of plastic pollution in some of the world’s remotest locations.

Also in 2018, after a year-long Greenpeace campaign to ‘Ban the Bag’ that included delivering a 65,000-signature strong petition to Parliament, the NZ Government announced a ban on single-use plastic bags.

“Today’s bag ban announcement is a great first step, but New Zealand needs a broad and comprehensive strategy to eliminate all sources of plastic pollution,” said Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Emily Hunter.

Greenpeace said the Government needed to stop playing catch-up, and move swiftly to ban other forms of single-use plastics, such as plastic bottles, as part of a comprehensive Plastic-Free New Zealand Plan.

Overfished West Coast Hoki fishery collapses

In September 2018 Greenpeace called for a full and independent inquiry into New Zealand’s Quota Management System after releasing a leaked internal Government report showing “shocking” levels of wrongdoing in the NZ Hoki fishery.

Fishing companies involved in the West Coast Hoki fishery revealed that they were struggling to catch fish in the fishery and as a result they agreed to temporarily give up 22% of their existing quota, and to stop fishing in spawning grounds.

Greenpeace said rampant overfishing in New Zealand’s most valuable fishery could only have helped drive the collapse. “History tells us that left to their own devices, the fishing industry will overfish and collapse fisheries – just look at what happened with Orange Roughy,” said Greenpeace Executive Director Dr Russel Norman.

Global Oceans Treaty

In October 2018, Greenpeace challenged the NZ Government to seize the day and help create the largest protected area on earth, right in our own backyard. A global movement of over two million people called on 24 governments, including NZ, to establish a 1.8 million square kilometre East Antarctic Ocean Sanctuary. More than 32,000 people signed the petition calling on the New Zealand Government to support the sanctuary proposal.

In April 2019 Greenpeace joined with scientists from the universities of Oxford and York to launch a report calling for 30% of the world’s oceans to be fully protected through a network of ocean sanctuaries and a binding Global Oceans Treaty ending destructive practices on the high seas.

https://www.greenpeaceoceanblueprint.org/

“The strongest possible Global Oceans Treaty would include a global body to designate, monitor and implement marine sanctuaries internationally,” said Greenpeace New Zealand Oceans Campaigner Jessica Desmond. “As yet the New Zealand delegation has not fully committed to this approach, but if we leave it up to regional bodies to do this we will get the haphazard ‘status-quo’ of oceans protection, which has failed so far.”

Two weeks later Greenpeace followed this by launching one of its biggest global conservation efforts to date, which called for a binding UN Global Ocean Treaty allowing a network of large ocean sanctuaries to be created across the globe.

In June 2019 Greenpeace welcomed the NZ Government’s announcement that it would put surveillance cameras on commercial fishing vessels operating within Māui Dolphin habitat, but said that far more needed to be done to protect the dolphins, including extending the existing marine mammal sanctuary to cover all Māui Dolphin habitat, and within the sanctuary, a ban on net fishing, seabed mining, and oil exploration and drilling.

“Putting cameras on boats is essential if we’re to have accurate reporting of key regulated measures such as by-catch,” said Greenpeace New Zealand Oceans Campaigner Jessica Desmond. “The Government must now roll out cameras on commercial fishing vessels across the country, to ensure the rules are followed.”

In August 2019, Greenpeace joined with other groups including World Animal Protection NZ, zoologist Dr Liz Slooten, and actor Robyn Malcolm to deliver a 55,000-signature petition to Parliament that called on the Government to increase protections for Māui Dolphins.

Greenpeace protesters covered Parliament lawn with replica corals in November 2019 and called on the Government to take urgent action to stop destructive bottom trawling in fisheries that targeted species such as Orange Roughy. The protest coincided with the release of new figures that revealed that up to a staggering 3,000 tonnes of coral had been destroyed by NZ bottom trawl vessels in 2018.

“The scale of the destruction caused by bottom trawling is immense. But when corals are pulled up in fishing nets, that’s actually only a tiny fraction of the destruction happening on the seafloor. For every tonne of coral brought up in the net, up to 340 tonnes are destroyed below,” said Greenpeace New Zealand Oceans Campaigner Jessica Desmond.

In early 2020 Greenpeace joined with Kiwis Against Seabed Mining (KASM) in welcoming the decision by the Court of Appeal to deny a mining company permission to dredge and mine 66 square kilometres of the South Taranaki Bight seabed as a victory for the oceans, and the Pygmy Blue Whales and Little Blue Penguins that inhabited the area. The Court of Appeal said the proposal did not meet a raft of environmental and Treaty of Waitangi principles, and therefore could not go ahead.

“We have to step back and recognise that seabed mining is simply too destructive to go ahead. We don’t know enough about our fragile marine environment and what mining could do – but the science shows the impacts would be negative,” said Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Jessica Desmond. “This particular mining operation would put endangered Hector’s Dolphins, Pygmy Blue Whales, seabirds, and coral life at risk. It’s a risk we cannot afford.”

Cameras on boats

In September 2020, Greenpeace launched a new petition calling on the Government to put surveillance cameras on 100% of NZ’s commercial fishing boats by the end of its term in 2023. Greenpeace said the past actions of the NZ commercial fishing industry had shown that it couldn’t be trusted to self-monitor and report on its own catches and ‘bycatch’ of non-target marine wildlife.

“Successive National and Labour Governments had both made commitments to delivering cameras on boats, but have failed to see it through. New Zealanders have had enough of the political pass-the-parcel. We refuse to wait any longer, and our struggling oceans can’t afford more delay tactics,” said Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner Jessica Desmond.

The Oceans Campaign’s ambitious agenda now is to ban throwaway plastics in order to prevent marine pollution; persuade the Government to set up a full and independent review of the Ministry of Primary Industries and Quota Management System; stop all bycatch of albatrosses, NZ Sea Lions and Maui Dolphins; ban set-nets, gill-nets and trawling in all Maui Dolphin habitat; ban bottom trawling; and protect 30% of the world’s oceans in marine sanctuaries and marine reserves by 2030, including the establishment of a giant East Antarctic Ocean Sanctuary in the Southern Ocean.