The Toxics Campaign

Turning the toxic tide

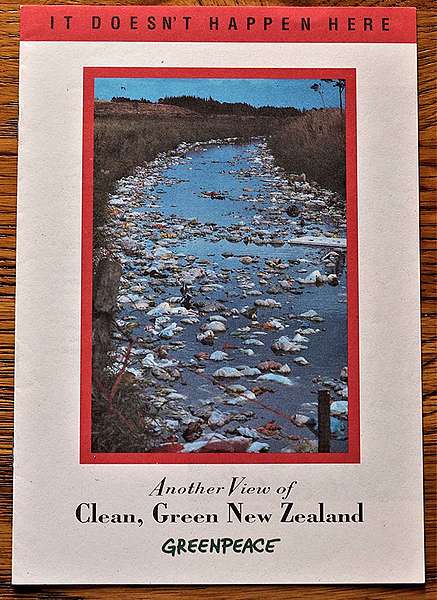

In 1990 Greenpeace expanded its Toxics Campaign team and hatched plans for an ambitious new public campaign to combat toxic waste, pesticide use, and the dumping of industrial and sewage effluent into rivers and coastal waters around New Zealand.

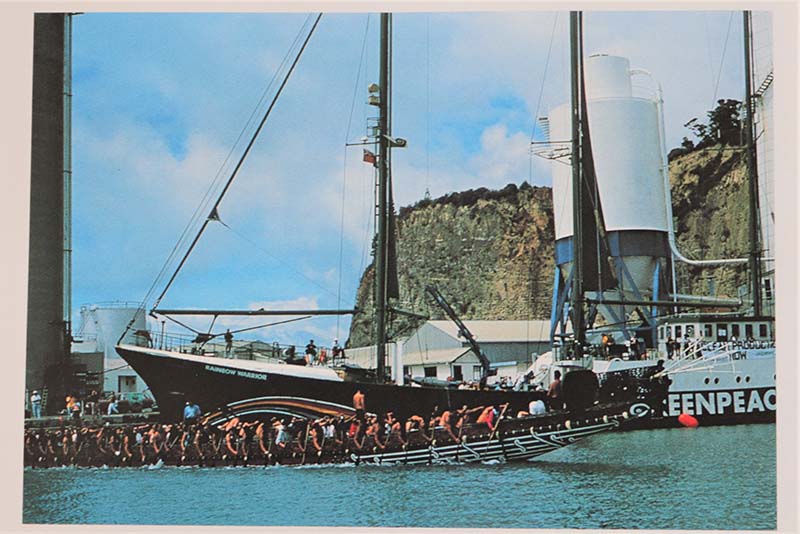

The new team set about researching these issues and building a network of contacts around the country in preparation for the first New Zealand tour of the new replacement for the original Rainbow Warrior, SV Rainbow Warrior II. The tour was named, ‘Turning the Toxic Tide’.

There was no shortage of pollution sources to investigate. At the time, New Zealand’s waste ‘management’ and disposal systems were outdated and based on the flawed ‘pollution by dilution’ approach that if it was dumped into a river or the sea, pollution would be diluted to the point of being harmless. The problem with that blinkered and unscientific view was that toxins can accumulate up the food chain and, along with pathogens contained in sewage and abattoir effluents, get into the shellfish, fish, and eels – kai moana – that local communities catch and eat.

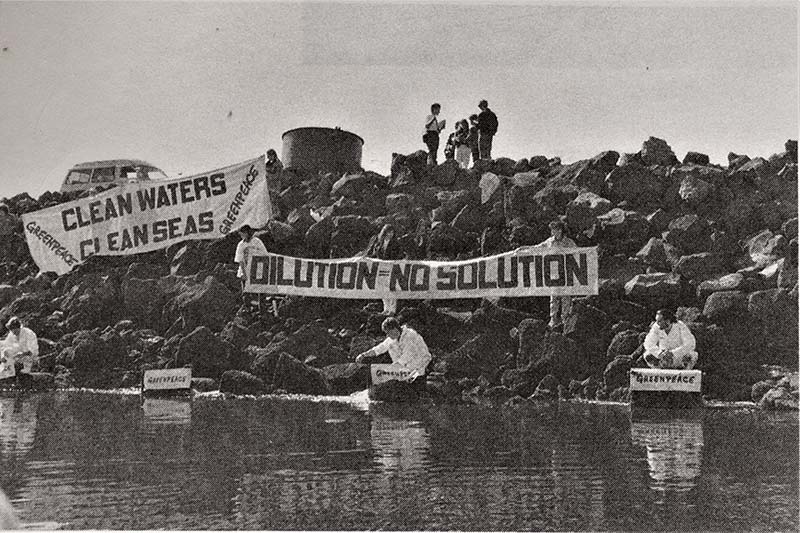

Prior to the tour, on 30 August 1990, a team of Greenpeace activists blocked all eight of the Auckland Regional Council’s (ARC) sewage outfall pipes at Mangere in protest at the ongoing pollution of the Manukau Harbour with most of Auckland’s sewage and hazardous industrial trade waste effluent. To emphasise the point, they set up a banner near the outfall pipes that read, “DILUTION = NO SOLUTION”.

Greenpeace called on the ARC to stop allowing hazardous industrial trade waste effluent to be dumped into the public sewage system in order to make it possible for the sewage solids to be treated and composted on land, and the residual liquid effluent treated to a higher standard in a new system of settling ponds.

Doing that, Greenpeace said, would massively reduce the amount of sewage and toxic pollution going into the Manukau Harbour, an internationally important site for migratory wading birds, habitat for the critically endangered Maui Dolphin, and an important recreational fishing area for mana whenua.

The new Rainbow Warrior tours New Zealand

In January 1991, SV Rainbow Warrior II embarked on a six-week tour of New Zealand. It was both a chance to continue documenting toxic pollution and to educate and help mobilise local communities to demand that local pollution be cleaned-up.

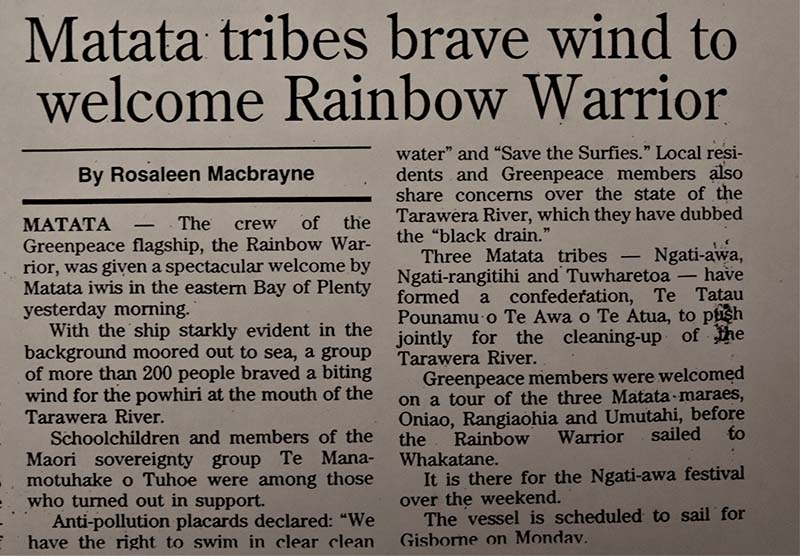

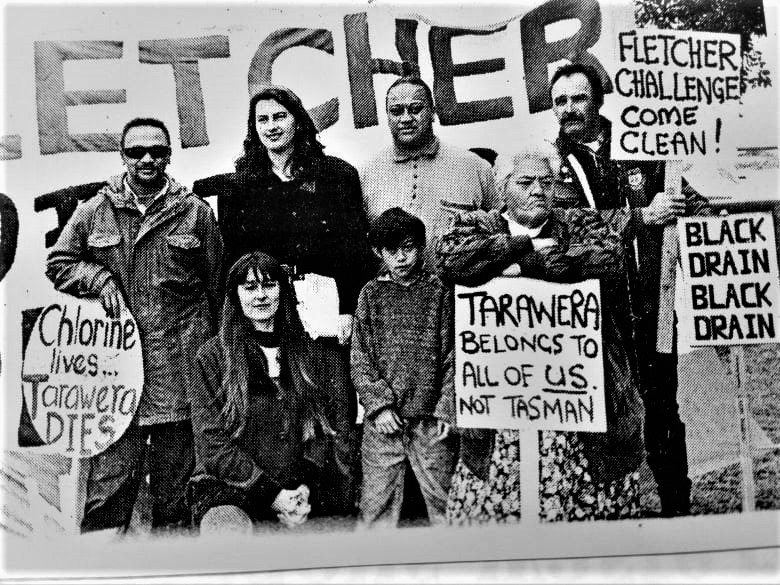

In the Bay of Plenty, Greenpeace joined with iwi and local communities to protest against the toxic Chlorine-based pollution that the Tasman Pulp and Paper factory in Kawerau was dumping into the Tarawera River, and toxic air pollution from the factory’s chimneys.

During the visit, crew and campaigners blocked and locked the Tasman pulp and paper factory’s pollution discharges into the Tarawera River

The Greenpeace flagship sailed clockwise from Auckland around the east coast of both islands, stopping in the main centres as far south as Dunedin and then turned back to Wellington and Nelson, north and west to New Plymouth and the Manukau Harbour, around Cape Reinga to the Marsden Point oil refinery, and back to Auckland.

Everywhere SV Rainbow Warrior II visited there was a warm welcome from the local community. Hundreds turned up for a powhiri on Matata beach before a protest outside Tasman’s Kawerau Pulp and Paper factory in the Bay of Plenty. The next day a team of Greenpeace activists and crew from the boat turned off the factory’s effluent discharge pipes and locked them shut, demanding an end to the toxic pollution of the Tarawera River and for the company to upgrade to a non-toxic oxygen bleaching system.

There were other stops to document and protest toxic and sewage pollution hotspots, including in Napier, Oamaru, Dunedin and Nelson.

At the end of the six-week tour, Greenpeace published a report on the extent of toxic pollution around the country and solutions for cleaning it up and preventing it in future, which was mailed to supporters, parliamentarians, and local and national decision-makers including councils.

In April 1992 the Tasman Pulp and Paper Company announced that it would replace its old Chlorine-making equipment in its No.1 Bleach Line, which produced newsprint pulp, and replace it with Sodium Hypochlorite. They did, however, continue using Chlorine and Chlorine Dioxide in the main No. 2 Bleach Line to produce bright white bleached pulp.

The change fell well short of installing the new state-of-the-art non-toxic oxygen-based pulp bleaching systems that Greenpeace had called for, and meant the company continued to dump tonnes of toxic organochlorines in the effluent it piped into the Tarawera River round the clock, every day of the year. It did, however, reduce the dioxin component in the effluent.

In Auckland, the ARC responded to public pressure by reviewing the trade waste rules that prescribed which commercial wastes were permitted to be dumped into the public sewage system. Public consultations took place in 1990-1991 with mana whenua, and community and environmental groups, including Greenpeace. As a result, the ARC agreed to a new trade waste by-law that excluded some toxic trade wastes and set more stringent limits on others. The old plant was replaced with a more effective land-based tertiary treatment system including biological and ultraviolet light treatment of wastewater. Residual biosolids are now mixed with soil and used to rehabilitate a local disused quarry site.

Another issue that came to the fore during the Turning the Toxic Tide tour was the deadly legacy of toxic PCP contamination at timber treatment sites. The number of these sites around the country ran into at least the hundreds – if not thousands – and this issue would become an important focus for the Toxics Campaign over subsequent years.

The NZ forest industry had major impacts on the environment and was in need of important reforms to improve its operations. Greenpeace’s Gordon Jackman also began campaigning for specific changes in the sector, especially the way that pine timber was treated using toxic chemicals such as PCP, and promoting alternatives to exotic pine monoculture plantations.

Another lesson learned from the tour was the importance of working with local communities and mana whenua to both identify toxic pollution problems and work together to stop pollution. After the tour, Hugh Sayers joined the Toxics Campaign team to liaise with mana whenua on toxic pollution issues.

Greenpeace’s door-to-door canvassing operations at the time had offered a network that connected with local communities in the main cities and provincial towns on pollution issues, and was a useful way to distribute information on pollution and other environmental issues.

In 1992, at a time when Greenpeace was scaling back its Antarctic expedition operations, the organisation moved from an office on Hobson Street to a smaller one in Parnell. The canvassing operations were also wound down and a new smaller telemarketing operation set up in its place.

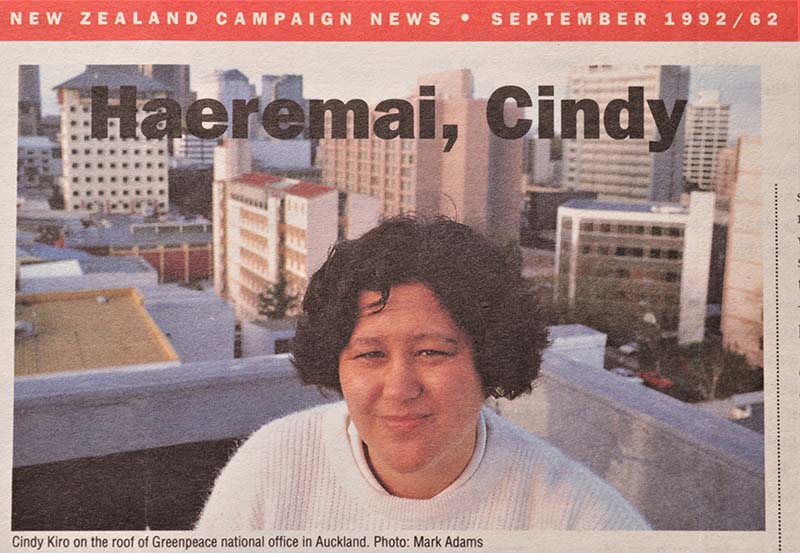

Greenpeace New Zealand appoints Cindy Kiro as its first Executive Director

In July 1992 Greenpeace New Zealand appointed Cindy Kiro (Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Hine) as its first Executive Director. As Greenpeace New Zealand’s Trustee, she attended Greenpeace International Annual General Meetings, and was soon elected to the Board of Greenpeace International in 1993.

In an interview in the Greenpeace New Zealand members’ magazine shortly after she started in the role she said, “We want to move to involving members more directly in Greenpeace’s activities and we must continue working in partnership with the community to effect change. We have a unique opportunity in New Zealand to work with Tangata Whenua to implement this concept of Kaitiakitanga.”

Looking back on her time as Greenpeace NZ Executive Director from 1992 to 1994, she recalls how she came to be elected to the Board of Greenpeace International at the 1993 AGM held in Crete: “I think the Greenpeace International AGM held in Crete in 1993 was the best overseas meeting I’ve ever been to. The international meetings I attended made me realise what an amazing diversity of people Greenpeace had from around the world.”

“It became clear to me that some cultures were extremely good at lobbying. Greenpeace UK was a master of process. Greenpeace UK often negotiated between the views around the table at the international meetings and that gave it power. Greenpeace UK Executive Director Lord Peter Melchett left Westminster, but Westminster went with him.”

“Steve Sawyer was there in Crete. Steve, as the previous executive director of Greenpeace International [1987-92] was very careful to hold back and not to interfere, although he did make comments if he thought it necessary.”

“I was elected to the Greenpeace International Board at that Crete AGM by a coalition of Greenpeace executive directors from Australia, Canada, Sweden, and the USA, which along with New Zealand were the ‘liberal’ offices that all had female executive directors. We would meet in the sauna with [Greenpeace Pacific Coordinator] Bunny McDiarmid and [Greenpeace NZ Campaign Manager] Stephanie Mills.”

“I’m very articulate and able to synthesise multiple views, and then articulate a view, so I became the group’s board candidate. I argued that we were important offices for Greenpeace’s work on oceans, climate change, and the wider Pacific region.”

“Threads and connections are important. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to Steve Sawyer for his unspoken patronage of New Zealand and the wider Pacific region. He understood us and he believed in us. I didn’t always agree with him, but he was a moral man and I saw that he had in his heart the memory of relocating the Rongelap community when he sailed on the Rainbow Warrior in 1985.”

“I thought that [Campaign Manager] Stephanie Mills was fantastic and I was very lucky to have a fabulous staff at Greenpeace New Zealand.”

After her time with Greenpeace, Cindy Kiro became Head of the School of Public Health at Massey University, and went on to serve as head of Te Kura Māori at Victoria University of Wellington, the New Zealand Children’s Commissioner, and Pro Vice-Chancellor (Māori) of the University of Auckland.

She received a PhD from Massey University and was appointed as the Chair of the Welfare Expert Advisory Group for the NZ Government in 2018. In 2021 she was appointed Ahorangi Chief Executive of the Royal Society Te Aparangi and in the 2021 New Years Honours she was appointed a Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to child wellbeing and education.

In May 2021, NZ Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced that Professor Dame Cindy Kiro had been appointed as the next Governor General of New Zealand.

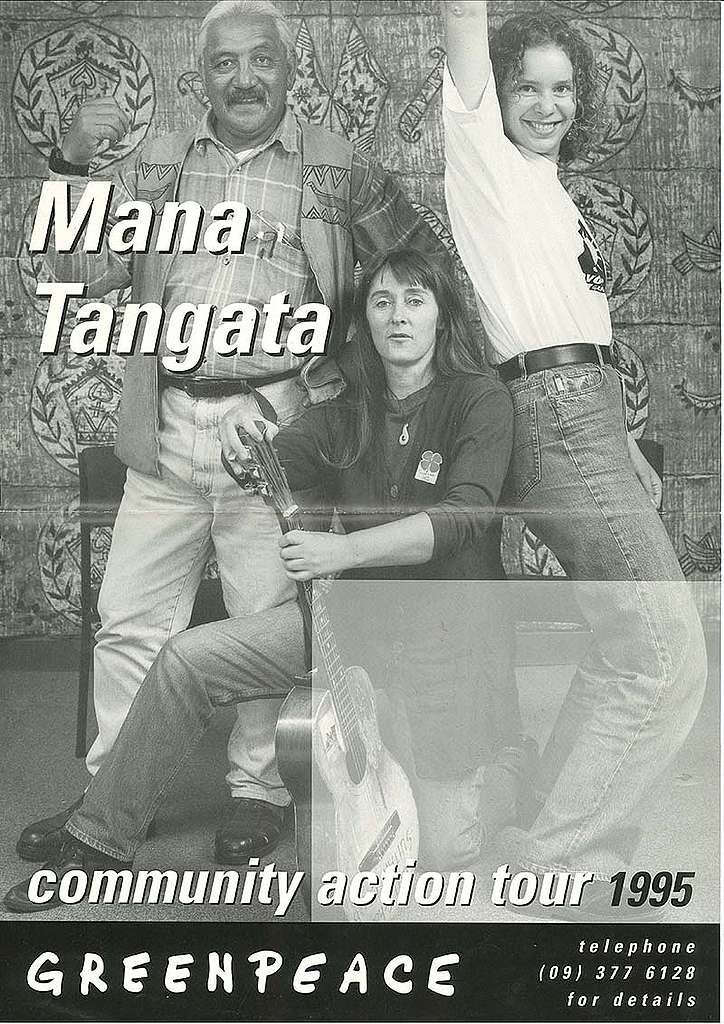

Mana Tangata

One of the first changes at Greenpeace New Zealand after Cindy Kiro’s appointment was the establishment in February 1993 of a new community organising arm of Greenpeace’s campaigns, called Mana Tangata.

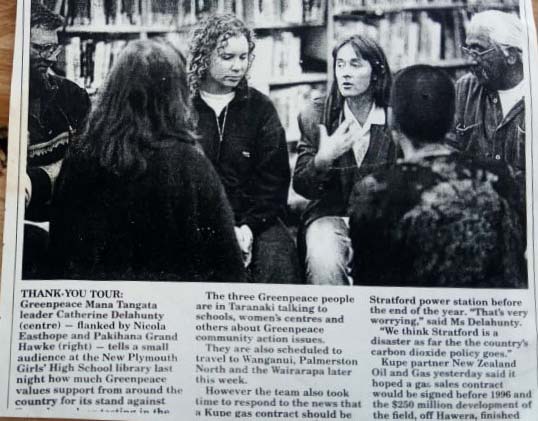

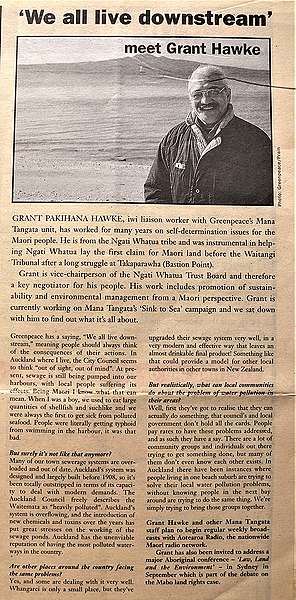

The Mana Tangata team comprised Team Manager and Fundraiser Mark Prain, iwi Liaison Grant Pakihana Hawke, Community Liaison Catherine Delahunty, and Education Outreach Nicola Easthope.

At the time, Greenpeace Executive Director Cindy Kiro described Mana Tangata as a dedicated team with skills in environmental activism and education that had been set up to, “benefit communities wanting to solve both their own problems and those we all face”.

Campaign Manager Stephanie Mills said that Mana Tangata would both, “work alongside local communities to help make a difference, and help make Greenpeace’s campaigns more relevant to local communities.”

The brochure published describing the new team and its work said they would share their skills to help support community action on environmental issues, share the latest scientific information on environmental issues from NZ and overseas, provide public speakers, and help develop educational programmes on environmental issues for schools and tertiary institutions, as well as produce new educational resources on environmental issues.

The role of Community Liaison Catherine Delahunty was to encourage community participation in environmental campaigns and help support community action on local environmental issues. As part of that work, she set up a Green Women’s Network that linked hundreds of women active on environmental issues around the country and provided information via a quarterly newsletter.

The role of iwi Liaison Grant Pakihana Hawke was to help give greater understanding of Kaitiakitanga, Tino Rangatiratanga, and the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi to local communities, and to help build relationships and alliances between iwi, Greenpeace, and local communities on peace and environmental issues.

Grant Pakihana Hawke met with iwi leaders and attended conferences, and was important in deepening the understanding of Te Tiriti o Waitangi within the organisation.

‘iwi Environmental Packs’ on environmental and resource management issues such as toxic waste, climate change, fisheries and forestry, were regularly mailed out to kaiwhakahaere on iwi trust boards, to Māori media such as RNZ programmes and Mai FM, and to interested individuals.

The role of Education Outreach Nicola Easthope was to run an environmental education programme for primary, secondary and tertiary students, and collaborate on projects that helped local communities address environmental issues that were of concern to them and to Greenpeace. She produced Tamariki Kakariki, a quarterly A4 colour magazine aimed at 5-13 year olds, and helped set up and coordinate the Green Team high school environmental network for 13-19 year olds which aimed to help youth participate in a wide range of environmental activities and campaigns.

As part of that, she also worked with the Green Team on the ‘Towards the GreenSchools’ project in 1994 which encouraged schools to carry out a stocktake of their resource use and make strategic plans to reduce their energy, water, and paper use. In 1995, she and Catherine Delahunty organised a national Green Team network hui in Wellington.

Nicola Easthope also worked on the ‘Sink to Sea’ project, which aimed to protect local streams and change the way that industry, schools, and households viewed and used freshwater and marine environments ‘from sink to sea’. That included participating in two community-based projects in Auckland that led to the production of an educational video by Team Video and an accompanying poster with educational resources that were widely distributed to schools and students around the country. The project was funded in 1994 by the NZ Lottery Grants Board.

Mark Prain managed the Mana Tangata team and was its fundraiser until he left to become Executive Director of the Sustainable Cities NGO in 1995. He went on to become the Founding Director of the Hillary Institute, an NGO that works on climate change, poverty, disease, peace, and justice issues.

In the early years of the 1991 Resource Management Act (RMA), Mana Tangata gave advice to community groups and tangata whenua on resource management issues, including on RMA submission processes and resource consent hearings.

A series of national skillshare tours followed in 1993, 1994, and 1995 aimed at helping community groups and tangata whenua working on environmental issues with technical information, skills development, and RMA advice.

Catherine Delahunty’s Community Liaison work also included representing Greenpeace at the 1994 Auckland water crisis hearings where she presented a powerful submission urging long-term water conservation measures and opposing the use of Waikato River water to supply Auckland’s drinking water because of the toxic pollution and sewage dumped into the river by the pulp factory at Kinleith and other pollution sources such as Hamilton’s sewage, which was mixed with Sodium Hypochlorite.

She also published a Green Women’s Network newsletter and led a 1994 delegation from the Women’s Environmental Network to meet with the Associate Minister of Health and Women’s Affairs. The delegation urged the government to phase-out the industrial use of Chlorine for pulp bleaching.

Mana Tangata worked closely with the Toxics Campaign, leading to the publication of “Cleaning up our Act – a guide to community action on PCP” and a land-based tour of communities facing toxic PCP and dioxin contamination undertaken by Toxics Campaigner Gordon Jackman and Community Liaison Catherine Delahunty.

During the six week tour they assessed PCP contaminated sites, advised on what could be done to clean them up, and promoted the Cleaning up our act guide.

They met with workers in the timber treatment sector affected by PCP contamination, local community groups, scientists, farmers, councillors, and journalists, and distributed a survey questionnaire about PCP contaminated sites to help build a database. The tour gave the PCP contaminated sites issue a higher profile in national and regional news media, and helped focus public pressure for contaminated sites to be cleaned up.

Nicola Easthope also organised and participated in a tour promoting the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary with Campaign Manager Stephanie Mills in 1994, which involved visiting towns closest to the 40-Degrees South latitude line of the proposed Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary, from Whanganui to Hastings. They had custom-made giant jigsaw puzzle pieces with each town on them so that at each stop the local mayor could add their town’s ‘piece’ to a jigsaw map of the 40-degrees South latitude line and pledge their support for the sanctuary.

She worked on another tour promoting sustainability in New Zealand fisheries with Oceans Campaigner Nikki Searancke in 1994 that involved her speaking to 1,600 school students at local primary and secondary schools about sustainability in New Zealand fisheries. She brought a custom-made giant painted papier maché model of an Orange Roughy with her to help explain the ecology of the deep ocean to the students. “The students loved the big papier maché Orange Roughy,” she recalls.

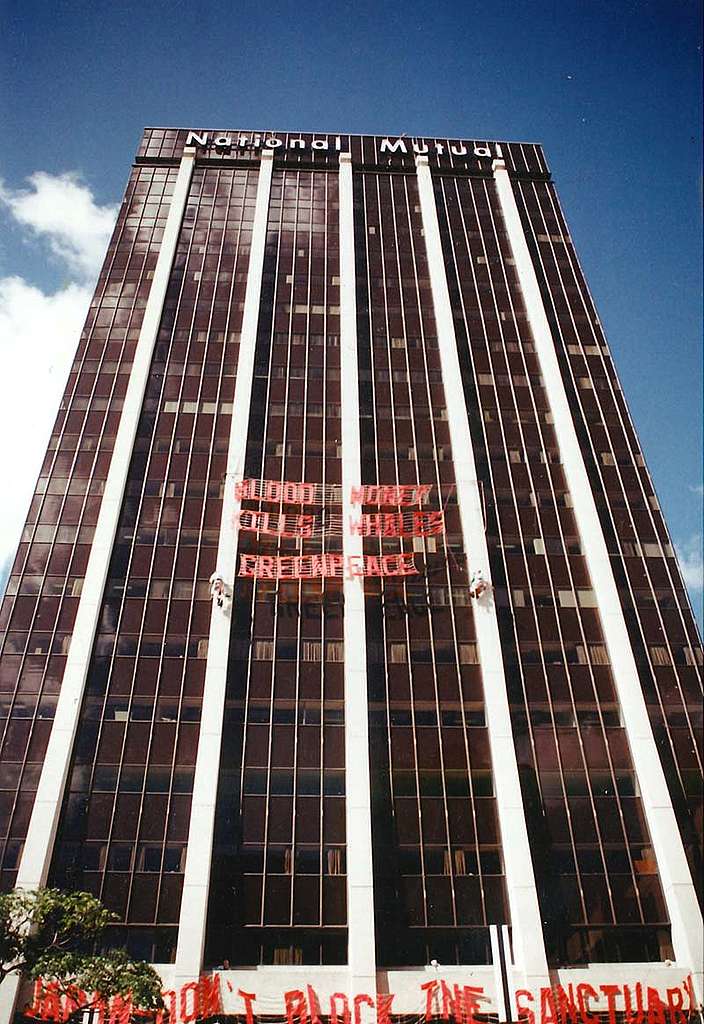

In February 1994 Nicola was also part of a team of Greenpeace climbers who hung giant banners at the Japanese Consulate office in Shortland Street, Auckland, that read, ‘Blood Money Kills Whales’ and ‘Japan – Don’t Block the Sanctuary’.

In February 1995 Catherine Delahunty, Nicola Easthope and Actions Coordinator Henk Haazen tracked down and boarded the whaling resupply vessel Oriental Falcon in the port of Timaru, and hung a large banner on the side of the boat that read, No Whaling in the Sanctuary. The vessel had been photographed by the MV Greenpeace’s crew supplying fuel to the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet inside the new Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary just days earlier. News media reporting of the action described them as “The Timaru Trio”.

In September-October 1995, the Mana Tangata team went on a six week land-based tour of the country from Kaitaia to Dunedin. During the marathon tour they organised 20 practical workshops on local campaigning and the environmental issues that Greenpeace was campaigning on such as nuclear testing, toxic pollution, climate change, marine protection, whaling, overfishing, and forestry. Their workshops were designed to engage with Greenpeace members, iwi representatives, environmental groups, women, youth and students, and to encourage debate on the Resource Management Act and local body decision-making.

During the tour a recurring concern for many communities was toxic pollution and the forest industry’s pine plantation monocultures that increasingly dominated NZ landscapes. They found that many Greenpeace members were also involved in local environmental issues and welcomed the opportunity to discuss them face-to-face.

Sink to Sea Video

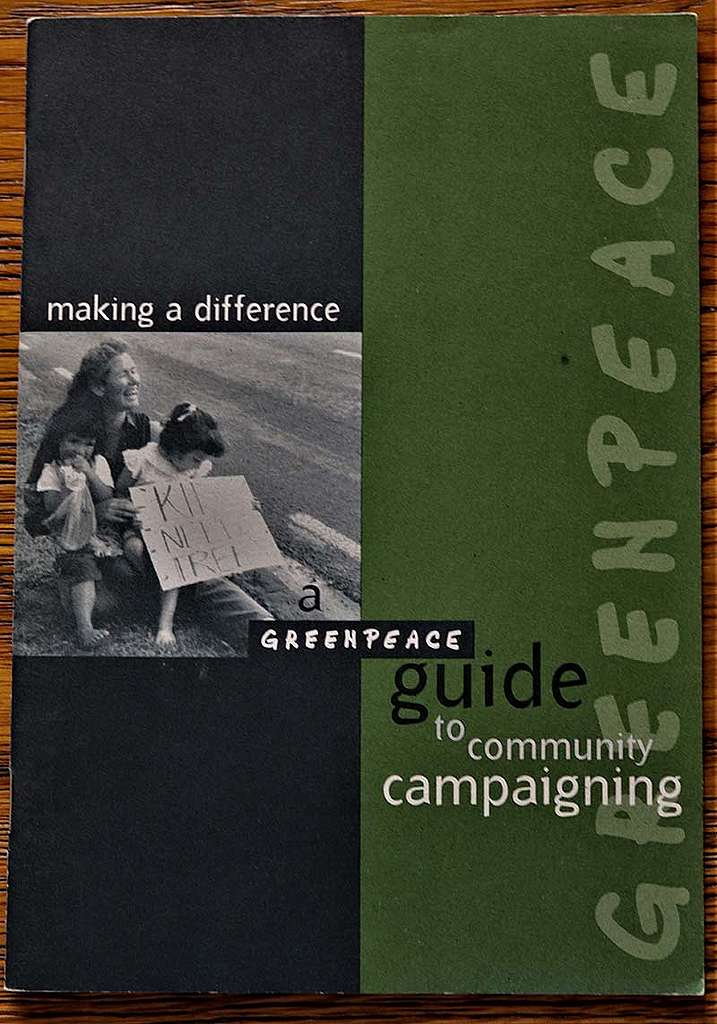

Mana Tangata’s popular Sink to Sea educational video about coastal and freshwater water quality issues featured prominently in the workshops, and they distributed copies of their new Making a Difference handbook on community campaigning and using the Resource Management Act.

They also distributed a set of educational factsheets they had written on the environmental issues that Greenpeace was campaigning on at the time to accompany their Greenpeace guide to community campaigning, which were funded by the NZ Lotteries Grants Board.

“We were also well-received by iwi representatives and iwi radio stations,” said Mana Tangata Community Liaison Catherine Delahunty. “Often, we were challenged to define Greenpeace’s perspective on the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori resource management issues.”

Concerns about PCP contaminated sites and the health of workers exposed to timber treatment chemicals were particularly important in the Bay of Plenty. “Everywhere we went people were looking for alternatives to pine plantation monocultures. Iwi were willing to have dialogue on a wide range of conservation issues in the context of respect for tribal needs and the Treaty,” said Mana Tangata iwi Liaison Grant Pakihana Hawke.

Mana Tangata also organised a series of meetings of the new Green Women’s Network in Hokianga, New Plymouth, Whanganui, Nelson, Greymouth, Dunedin, and Christchurch during the tour. A key concern for many participants was the link increasingly being made between toxic pollution and human health.

The Mana Tangata team also attended an activists’ conference on environmental issues and Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1995, and published a report on working with Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Catherine Delahunty became Greenpeace’s Toxics Community Campaigner in 1996 before she left to join the Kōtare Trust where she worked as a conservation, RMA, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, facilitation, and social justice tutor for the Trust and for a number of Polytechnics.

She was elected to Parliament as a Green MP in 2008 and served three terms until 2017. Her portfolios included education, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, toxics, disability rights and freshwater. Since stepping down from Parliament she has created her own sell-out show with her director sister about Parliament, “Question Times Blues”, and was elected to the Greenpeace New Zealand Board in 2018. She now chairs the Board’s committee on Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Looking back on her time with Mana Tanagata she recalls how the work of the team evolved: “I took the Community Liaison role into the Women’s Environment Network space and supported Grant Pakihana Hawke’s work with tangata whenua, and supported the campaigns such as the Toxics Campaign work in the Bay of Plenty.”

“Grant Pakihana Hawke’s role was bridge builder and he opened doors for us with tangata whenua, marae, and ropu working on environmental issues.”

“Mana Tangata backed-up Greenpeace’s campaigns when it was important, such as the Toxics Campaign work in the Bay of Plenty, where Gordon Jackman had developed and sustained relationships with tangata whenua and community groups over the years. My role was also to build links with the three iwi representatives there in Te Tatau Pounamu o te Awa o te Atua.”

“During the tours we explained Greenpeace’s role. The difficult dance sometimes was having to apologise for things that Greenpeace hadn’t followed up on in the past, or having to explain that Greenpeace couldn’t take on everything.”

“We tried to play a brokering role with communities and Greenpeace’s campaigns.

We also supported the campaigns such as when we joined the whaling action in Timaru in 1995 and worked on the Auckland water crisis hearings in 1994.”

“I went to the hearings with Grant Pakihana Hawke and made submissions on the Waikato River water pipeline proposal, particularly the toxic pollution and sewage issues.”

“The highlights for me of Mana Tangata were the tours that we did and the big Green Team hui that we organised at Taputeranga Marae in Island Bay, Wellington.”

“We met and engaged with communities and carried out activities when we could add value, such as with the Women’s Environment Network and the Green Team youth network – on the links between toxic chemical exposure and breast cancer, and the ‘Sink to Sea’ project.”

“We also produced a small handbook on working with Te Tiriti o Waitangi that tried to crystalise learnings from Mana Tangata’s work on Te Tiriti issues and Gordon Jackman’s experience working in the Bay of Plenty, to help people avoid pitfalls when they had no experience of working with tangata whenua, such as the importance of recognising mana whenua, being open about your agenda, and a willingness to negotiate goals where there was common ground.”

“Mana Tangata was yet another attempt by Greenpeace at trying to come to grips with, and show respect for, Te Tiriti o Waitangi and tangata whenua, and to give Greenpeace more outreach capacity and help to develop appropriate relations with tangata whenua.”

“Mana Tangata did a lot of work in this space. It’s a long journey and sometimes it has come in waves. The organisation needs a more structural way to do this in future, and not rely on the long-term presence of individuals in the organisation willing to continue this work.”

Following her work with Mana Tangata, Nicola Easthope went into the teaching profession and was the Enviroschools facilitator on the Kāpiti Coast for a few years. She currently teaches English and psychology at Kāpiti College and coordinates the Eco Action Group, which develops and nurtures young environmental and social justice activists. Nicola wrote the part of a Pākehā settler woman for the sell-out school production, Parihaka in 2019-20. She has also published two collections of poetry: Leaving my arms free to fly around you (Steele Roberts, 2011) and Working the tang (The Cuba Press, 2018), and has featured as a guest poet at writers’ festivals in Queensland, Tasmania, Wellington, and Manawatū. She also writes a blog of poetry and reviews.

Looking back on her time with Mana Tangata, Nicola Easthope says is especially proud of the work she did on the ‘Sink to Sea’ project and with the Green Team youth environment network: “After we made the ‘Sink to Sea’ video with Joel Cayford, I visited schools with Catherine Delahunty to give talks that linked the environmental issues in the video to the issues raised by taking polluted Waikato River water and using it as a drinking water supply in Auckland.”

“We also showed clips from the video when we were on tour to showcase successful local campaigns against pollution.”

“The ‘Sink to Sea video’ had segments about the campaign to clean up the Tarawera River; Lorraine Adams’ campaign to clean up pollution in Oamaru harbour; the campaign to clean up PCP contamination of Lake Rotorua; and the work of the Hoani Waititi school students to clean up Wairau Creek in West Auckland.”

“The video was part of a cross-curricular project which included English, Art, Social Studies, and Science content in the teaching notes that accompanied the video.”

“The ‘Sink to Sea’ project was also fun. We learned how to walk like a heron in the mangrove and we wore plastic bin bags around our thighs so we could wade through the stream during the surveys.”

“I also really enjoyed singing waiata with Catherine when we visited schools for our talks. We’d practice our waiata in the enclosed car park under the Greenpeace office in Parnell, which had good acoustics.”

“When the Ministry of Forestry and the Forestry Industry produced a school resource that sang the praises of exotic pine monoculture plantations, we wrote to every secondary school science teacher in the country with a counter-view setting out the negative impacts of pine plantations on the environment that we developed with the help of Greenpeace’s Ecoforestry Campaigner Grant Rosoman.”

“The highlights of Mana Tangata for me were working with the Green Team teenage students’ network in Auckland schools. The national hui that we organised at Taputeranga Marae in Island Bay in Wellington in 1995 was the climax of all that.”

“The tours we did together as Mana Tangata and with campaigners were also a highlight.”

“I also enjoyed working on the ‘Great NZ Beach Tour’ we did on a bus with Auckland band the ‘Paua Fritters’ in January 1993. For that we drove the bus around beaches from the Hokianga to Opotoki to talk with the public about ozone depletion and coastal pollution issues.”

“Working biculturally was an education for me and has informed my whole life since then.”

“I remember working in collaboration with Georgina Stewart at the Kura Kaupapa at Hoani Waititi in West Auckland.”

“I also remember going to Parihaka Marae in 1991 with a group of Greenpeace canvassers when I managed the Greenpeace Canvass Office in Wellington. We met Milton Te Miringa Hohaia there and he talked about his vision for an off-grid solar-powered Pa, which was inspiring.”

“We also had a bit of fun while we went to look for MV Oriental Falcon. We jokingly called it ‘Operation Teddy Bear’s Picnic’ after we saw a pre-school picnic in the park opposite a motel we were staying in. It was also an adventure. We were painting the banner in the car headlights one night when we got a tip the ship was going to the port of Timaru, so we had to get there in a hurry. While we practiced how to lock onto the ship in a motel room, Catherine dropped the lock key and it nearly disappeared into the sink hole while she had the D-lock around her neck and was attached to the sink pipe.”

“At a bar near the port that we visited a group of Filipino crew from one of the ships already in port were on the dancefloor, so Catherine got chatty while dancing with one of them called Ramon to see if he knew anything about when MV Oriental Falcon was due in port. We also took turns doing shifts keeping watch for it during the night.”

“Then, after all the careful planning and preparations, when the ship arrived in port at mid-day the next day we were able to just walk straight up the gang-plank and onto the ship, and lock onto the side rails without anyone even seeing us.”

“Once we had the banner out and the local TV crew turned up to film us, we realised we were quite hungry so we called a pizza delivery place and they came down with our pizza and walked up onto the boat and delivered it right into our hands, which was quite amusing at the time because pizza delivery was quite a new thing in NZ back then.”

“Some Wharfies also came over with cups of coffee for us and we got to see the ship’s log which showed that they had resupplied the Japanese Government’s whaling fleet inside the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary.”

“We also joined in with the Shell boycott Day of Action in Auckland in 1995, setting up a picket line at the Shell station at the top of Williamson Avenue in Grey Lynn urging people to boycott Shell over the company’s appalling practises in Nigeria and role in the military regime’s execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his eight Ogoni compatriots who were campaigning to protect the environment in the Niger Delta from company oil spills and leaks. We got a lot of support from the public on that.”

“I also remember an Auckland airport protest against the Norwegian IWC Commissioner. I got dressed up as a waiter with a big painted foam ‘whale steak’ on a platter. We chanted slogans and generally made it clear to him that New Zealanders didn’t want anything to do with whaling.”

“Greenpeace felt like a diverse family. We worked together and we socialised together, and the boundaries between the personal and the work blurred.”

“It’s great to see that some of the participants in the Green Team network and collaborators from the ‘Sink to Sea’ project back then are now working to make a difference for the environment. Carmen Gravatt is now Greenpeace East Asia Programme Director, Niki Gladding is a councillor on Queenstown Lakes District Council, and Tim Park is Environment Partnership Leader at Wellington City Council.

After his iwi liaison work with Mana Tangata, Grant Pakihana Hawke continued working on environmental and RMA issues as Deputy Chairman and then Chairman of the Ngati Whatua Trust Board in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Gordon Jackman continued working as a Greenpeace campaigner until 1994. He was elected to the Greenpeace New Zealand Board, serving as Board Chair from 2000 to 2002 when he stepped down to participate in the Green Party negotiating team after the 2002 general election. He was elected to the Greenpeace New Zealand Board again from 2006 to 2010, and wrote a report for Greenpeace on the New Zealand agricultural sector in 2006.

Since his time as a Greenpeace campaigner, he has worked as an environmental science consultant with Jackman & Black Environmental, and an archaeologist based in Gisborne/Turanga. He has continued to campaign for the clean-up of toxic contaminated sites, including negotiating funding for site clean-up operations as part of a Green Party MOU with Environment Minister Nick Smith and the National Government.

He is now Chief Executive of the Duncan Foundation, a national support service for people living with neuromuscular conditions, and the health professionals who treat and support them. He is also on the National Ethics Advisory Board (NEAC) and the Board of the Supported Lifestyle Trust of Hauraki.

Looking back on his time as a Greenpeace campaigner in the 1990s he says, “I think an interesting thought experiment would be to imagine what would have happened if Greenpeace hadn’t existed? In order to affect the future, we need to see how we’ve changed the present.”

“Without Greenpeace there would still be driftnet fishing in the Pacific, whaling in the Southern Ocean, nuclear testing at Moruroa, and metres-thick dioxin contaminated foam floating on the Tarawera River. But we had to fight tooth and nail to stop all that.”

“Greenpeace did a lot of really fantastic work in the 1990s with ecological narratives such as the interconnectedness of our activities on our environment and our health, and of our energy use on the global climate. In some ways, Greenpeace’s most powerful ability is reframing what’s possible.”

The Plantation Effect

Another important aspect of the Toxics Campaign was its work to shift the NZ forest industry away from its exotic pine monoculture model and reliance on toxic treatment chemicals, towards ecoforestry and ecotimber products that did not require toxic treatment chemicals.

Campaigners Gordon Jackman and then Grant Rosoman developed a critique of the environmental impacts of the NZ forest industry and produced resources to promote ecological alternatives, with a particular focus on environmental certification.

In August 1994, Greenpeace published The Plantation Effect, which summarised the serious environmental impacts of exotic plantation forestry in New Zealand.

The report challenged the NZ forest industry’s exotic pine plantation model and its claims of sustainability, and challenged the industry to adopt practices that restored native biodiversity back into the landscape by planting native species and mixed tree systems, stopping the use of toxic chemicals, and adopting systems that maintain soil, water, and air quality. It pointed out the environmental problems with the use of pesticides in forestry, the use of exotic monoculture plantations, and the extraction methods used on steep land and the creation of ‘slash’.

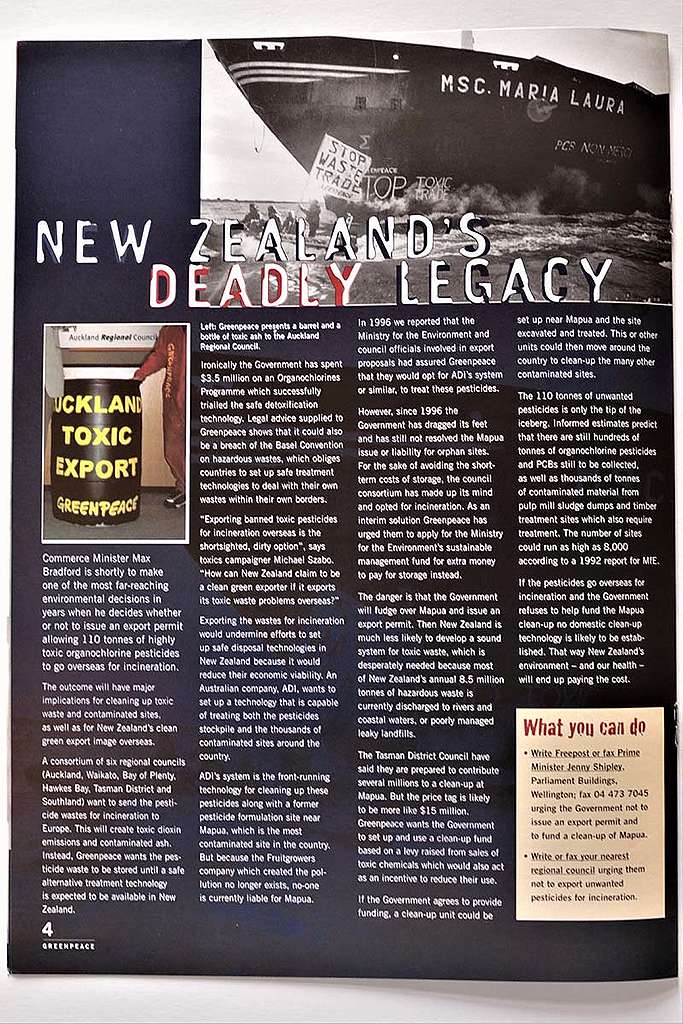

In 1992 and 1994 Greenpeace published two related reports, one on PCP and dioxin contamination called ‘The Deadly Legacy’ by Gordon Jackman, and the other called ‘Zero by 2000’ by Michael Szabo and Tim Birch. Both reports urged a phase-out of organochlorine pollution by the year 2000 and set out policies for cleaning-up contaminated sites and rehabilitating the affected land.

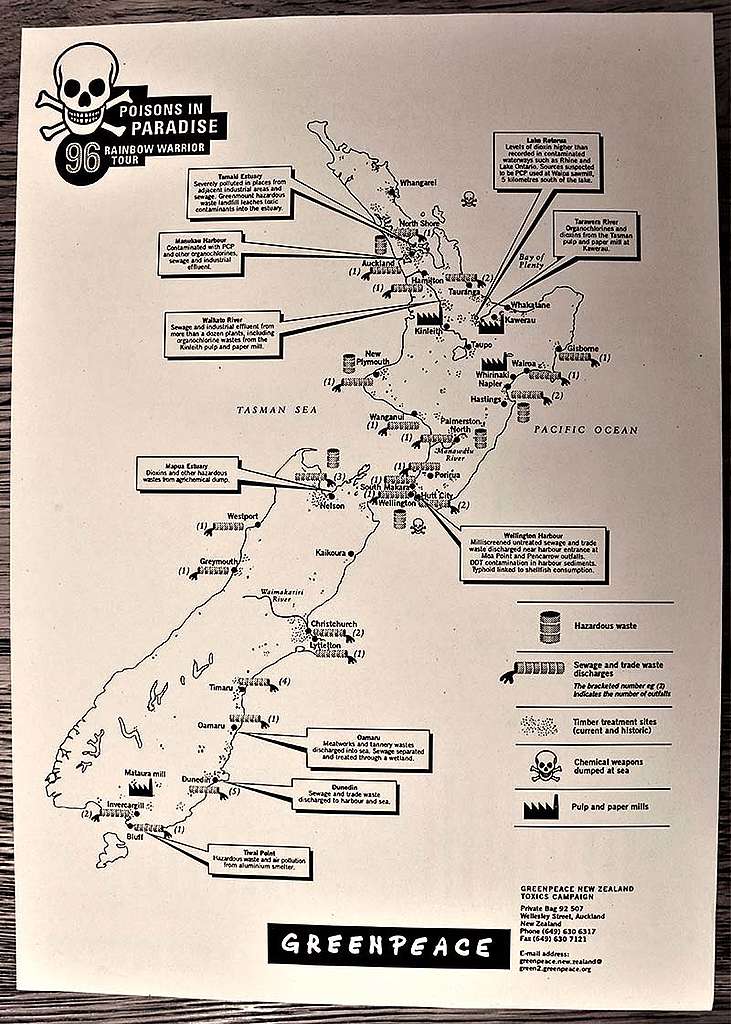

Another SV Rainbow Warrior II tour targeting toxic pollution was to have followed in 1995, the ‘Poisons in Paradise Tour ’, but that had to be postponed and rescheduled when Greenpeace sent SV Rainbow Warrior II to lead the campaign against the resumption of the French Government’s nuclear testing programme at Moruroa Atoll in 1995.

Poisons in Paradise

The postponed ‘Poisons in Paradise Tour’ went ahead in June 1996 with port visits along the east coast of the North Island from Auckland to Wellington and over Cook Strait to Nelson.

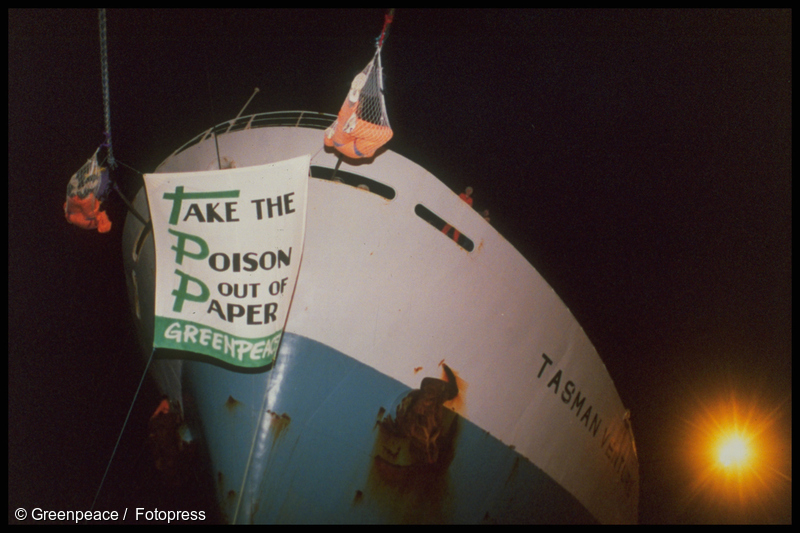

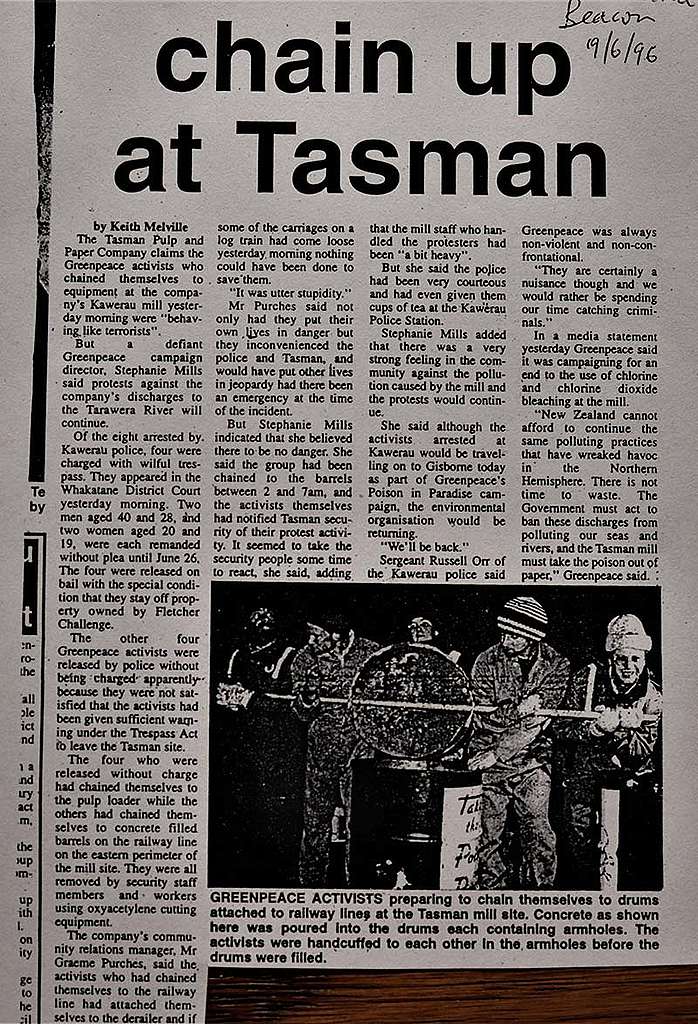

When SV Rainbow Warrior II arrived in the port of Tauranga, Greenpeace activists boarded the cargo ship MV Tasman Venture to delay its departure carrying Chlorine-bleached newsprint pulp from the Tasman Pulp and Paper factory to Australia. They locked themselves to the ship and hung banners that read, ‘Take the Poison out of Paper’. Greenpeace renewed its call on the company to switch to a Totally Chlorine-Free oxygen-based bleaching system.

During the tour Greenpeace also released ‘Measuring Up’, a report compiled by Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo containing the results of a nationwide survey of councils that asked them how much industrial trade waste and sewage effluent was being dumped into the nation’s rivers and coastal waters. The survey found that more than 1.3 billion litres of industrial trade waste and human sewage effluent was being dumped into rivers and coastal waters every day. The exact figure was even higher because 36 councils out of the 150 contacted did not reply to the survey despite repeated requests.

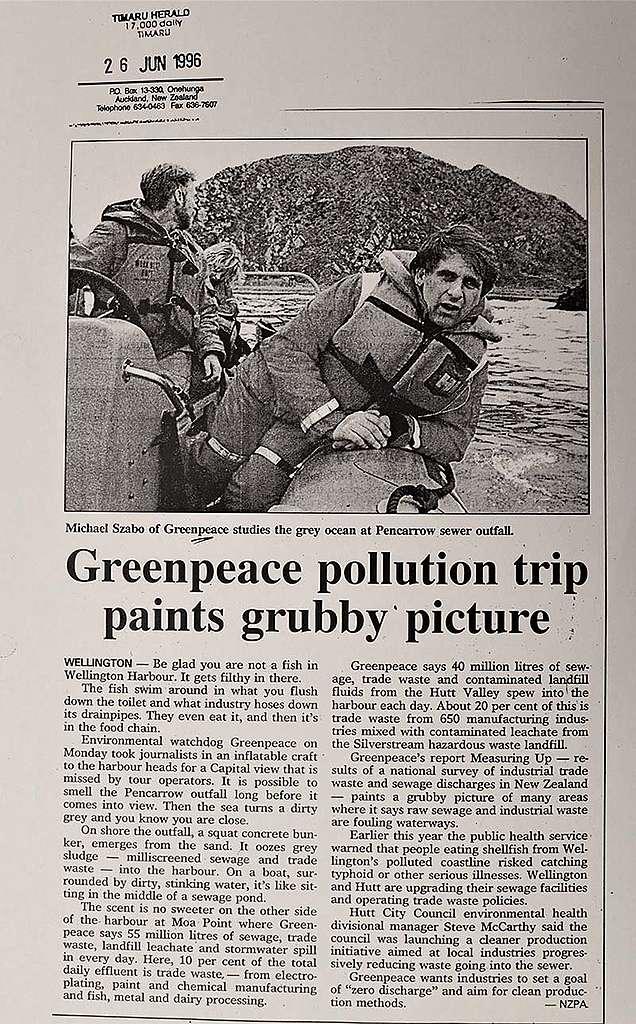

After SV Rainbow Warrior II arrived in Wellington Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo took journalists to visit Hutt City’s sewage and trade waste outfall pipe which discharges effluent into the sea at Pencarrow Head close to the entrance to Wellington Harbour, 10 kilometres from the Beehive.

“This is one of the worst examples of marine pollution in New Zealand. Forty million litres of sewage effluent, toxic trade wastes, and contaminated landfill leachate is discharged into the sea here every day,” Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo told them. “Toxic trade waste makes up 20% – or 8 million litres per day – of the effluent and contains toxic heavy metals and industrial solvents from 650 manufacturing sites in the Hutt City area, including electroplaters, chemical manufacturers, paint manufacturers, battery manufacturers, battery smelters and dye makers.”

The tour also highlighted pollution from the Pan Pac pulp factory discharging waste effluent into the sea near Napier in Hawkes Bay, and the worst contaminated site in the country at the former NZ Fruitgrowers’ Chemical Company site in Mapua where pesticides were produced, stored, and used for decades from 1945 to 1988.

In late 1996, the first MMP general election resulted in Jim Bolger’s National-led Coalition Government supported by the NZ First Party, which had itself splintered from the National Party. The incoming Government announced policies to phase-out organochlorines such as dioxin and to regulate toxic waste, and started to develop standards for cleaning-up toxic pollution in 1997.

At the same time, Greenpeace continued to alert the public to the main sources of organochlorine and dioxin pollution such as waste incinerators, pulp and paper factories, steel factories, pesticide manufacturing and distribution sites, and timber treatment sites.

Zero by 2000

The campaign’s strategy was to help educate the public in local communities affected by organochlorine and dioxin pollution, and to mobilise people against the pollution around a demand for Zero by 2000. This was a way to put public pressure on the polluters, regional and district councils, Ministry for the Environment, and the Government to implement a phase-out by the year 2000. It also promoted strong toxic waste regulations covering industrial trade waste discharges to the environment via public sewage systems, and a clean-up of toxic contaminated sites.

In 1996 a group of five renegade regional councils (Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Hawkes Bay, Southland) announced a plan to export stockpiles of old unwanted toxic organochlorine pesticides for dirty incineration overseas. Greenpeace called on them to abandon their damaging plan and instead wait for a new, clean dechlorination technology from Australia to be approved for use in New Zealand, that could safely treat the unwanted toxic pesticides and dioxin contaminated soil.

At the time the Organochlorines Programme managed by the Ministry for the Environment was funding a trial of a new dechlorination technology aimed at safely cleaning up New Zealand’s many toxic contaminated sites and wastes. This was something that Greenpeace had strongly advocated for, which was represented on the programme by Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo.

By announcing their plan to export the pesticide stockpiles that they had gathered with funds from Ministry for the Environment, the five renegade councils were directly undermining the financial viability of the new dechlorination technology in NZ and paying to ‘pass the buck’ of a toxic problem generated by NZ farmers on to local communities living around a dirty toxic waste incinerator in The Netherlands, where burning the chemicals would produce toxic dioxin emissions to air and residual toxic ash.

Te Tatau Pounamu o te Awa o te Atua and Greenpeace

In the Bay of Plenty, Te Tatau Pounamu o te Awa o te Atua (The Greenstone Door to the River of the Gods), a coalition of iwi representatives from Ngati Awa (Pouroto Ngaropo), Ngati Rangitihi (Tipene Marr) and Tuwharetoa ki Kawerau (Tairua Whakaruru), formed an alliance with Greenpeace in 1996 to oppose the company’s pollution of the Tarawera River.

Greenpeace also carried out a series of direct actions targeting Tasman’s Kawerau factory during 1996 and 1997 that helped propel the issue onto newspaper front pages and make radio and TV news headlines.

These actions included scaling and occupying the factory’s giant pulp digester tower to hang a banner that read, ‘Chlorine Kills’.

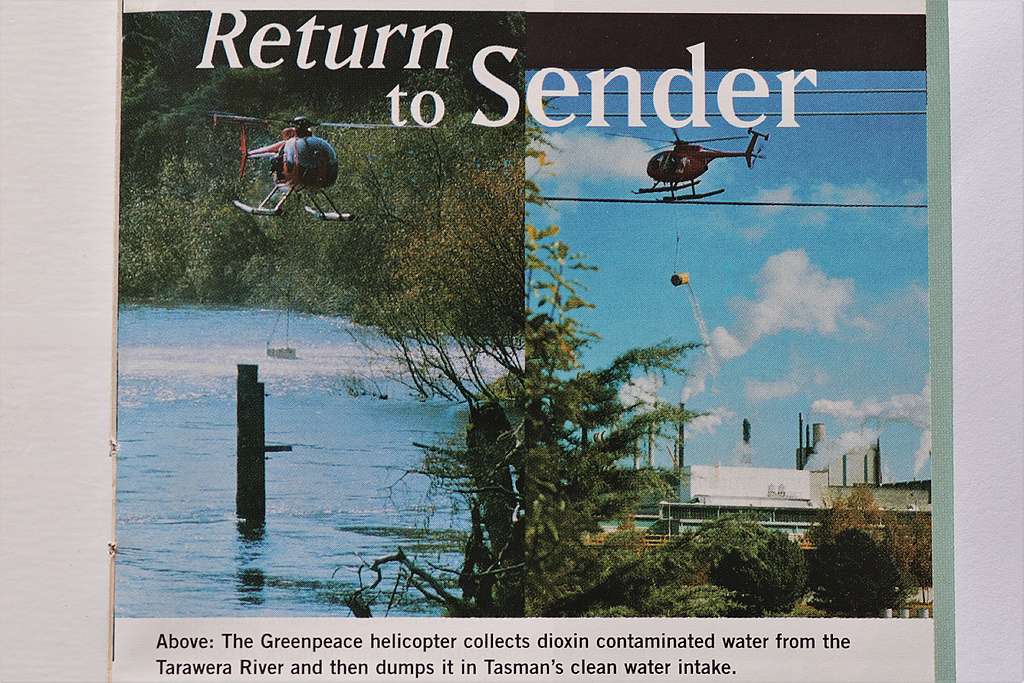

Using a helicopter to scoop up effluent from where the factory’s discharge pipe dumped into the river and flying it back to the intake to dump it there so the factory had to ‘recycle’ its own waste.

And blockading a train carrying bleached pulp from the factory to the port of Tauranga by locking down the railway line at the factory gate using 44-gallon drums filled with concrete.

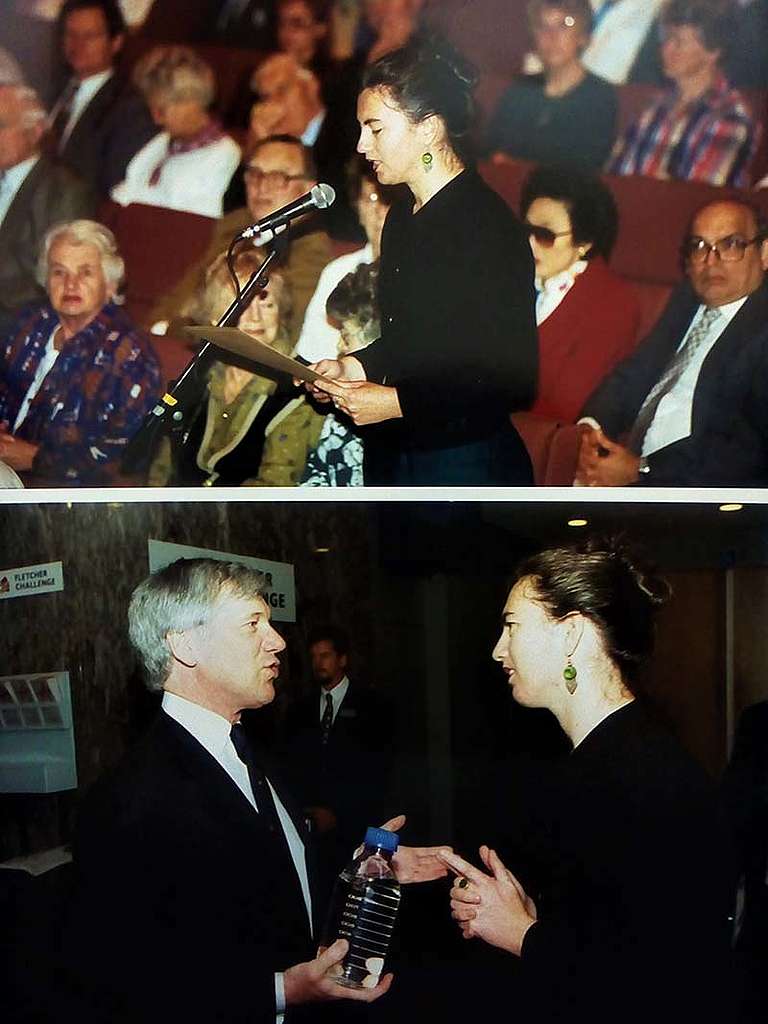

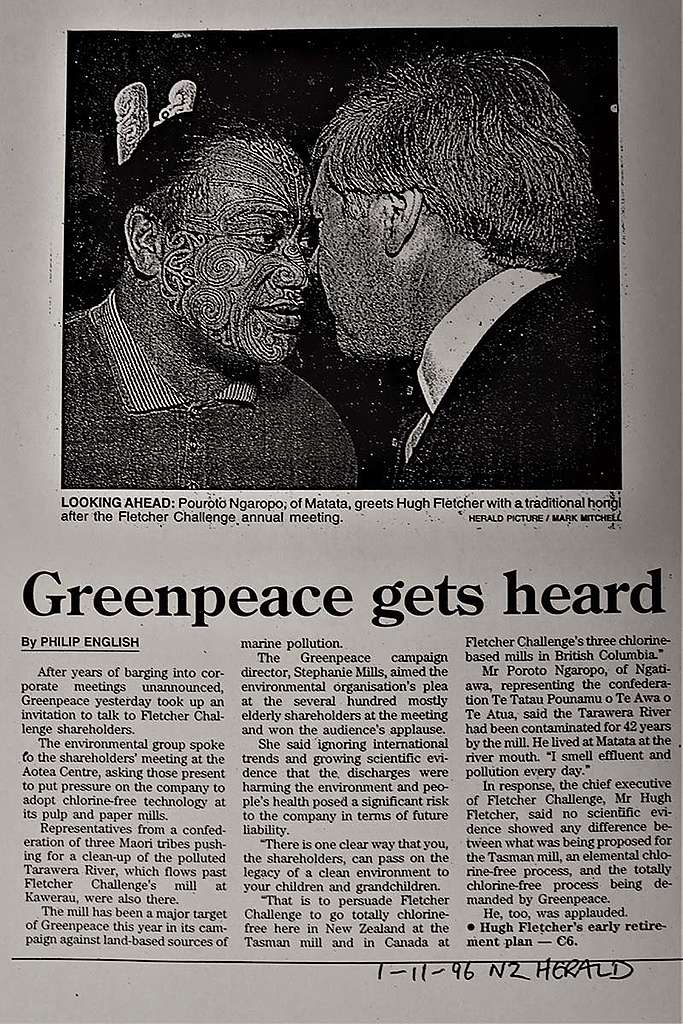

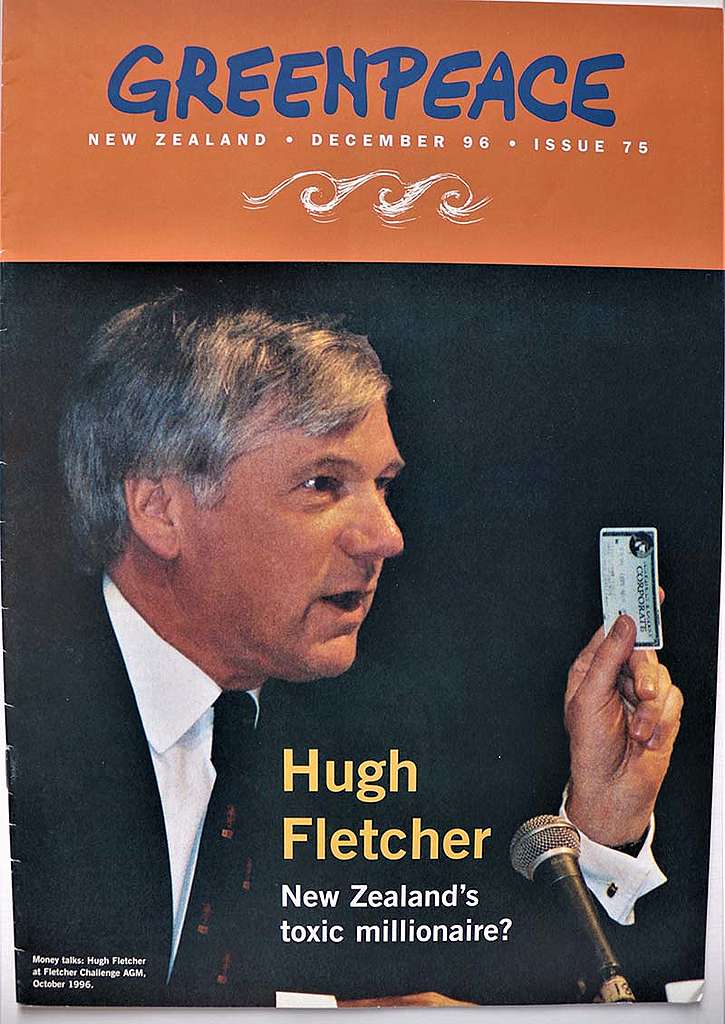

Greenpeace Campaign Manager Stephanie Mills spoke at the Fletcher Challenge AGM in Auckland with Pouroto Ngaropo, the Ngati Awa representative from Te Tatau Pounamu o te Awa o te Atua (The Greenstone Door to the River of the Gods).

She told the meeting that scientific research showed that enough was already known about the health and environmental risks of dioxins and organochlorines to justify a shift to Totally Chlorine-Free (TCF) pulp production. She also urged shareholders to mandate the company to adopt the precautionary approach and convert all of its pulp mills in New Zealand and Canada to TCF systems.

Pouroto Ngaropo urged shareholders to visit the Tarawera River in the Bay of Plenty and challenged them to take a cup and see if they would want to drink the polluted water. He also quoted to shareholders the words, “I am the river; the river is me”.

The rest of the meeting was dominated by shareholders asking the company questions about its environmental impacts.

When Hugh Fletcher met Stephanie Mills after the speech, she handed him a bottle of oxygen bleach, the non-toxic alternative to the Chlorine-based bleach that the company used to bleach wood pulp, and challenged him to ‘front-up’ to the company’s critics in the Bay of Plenty and to join with members of Te Tatau Pounamu o te Awa o te Atua, local communities and Greenpeace on a hikoi along the Tarawera River from its source at Lake Tarawera to the sea.

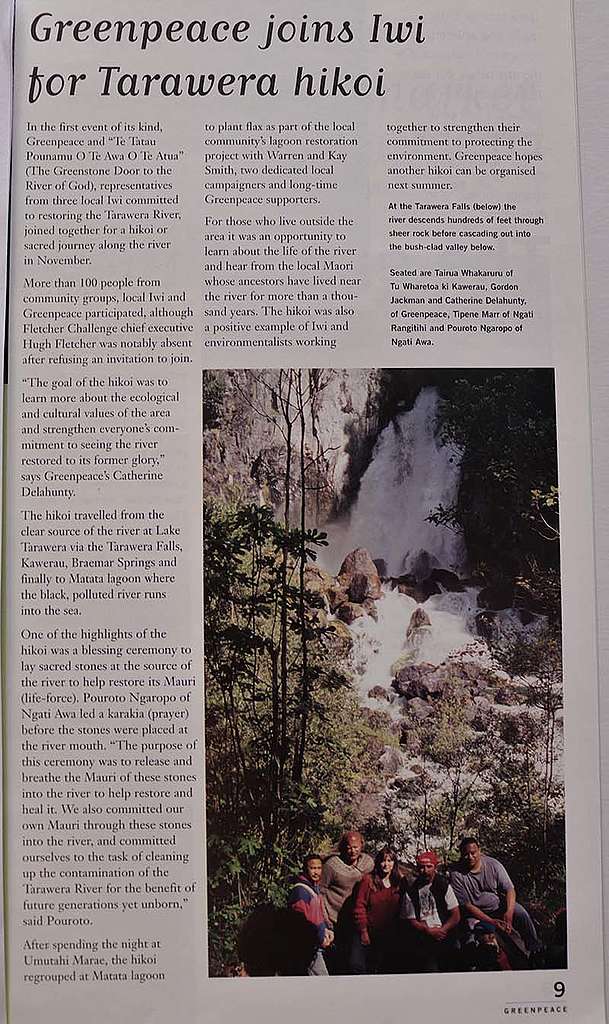

Hugh Fletcher declined the invitation, and the hikoi went ahead without him. In November 1996, Greenpeace and Te Tatau Pounamu O Te Awa O Te Atua joined together for a hikoi or sacred journey along the Tarawera River. More than a hundred people from local iwi and community groups, and Greenpeace staff, participated.

“The goal of the hikoi was to learn more about the ecological and cultural values of the area and strengthen everyone’s commitment to seeing the river restored to its former glory,” said Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Catherine Delahunty.

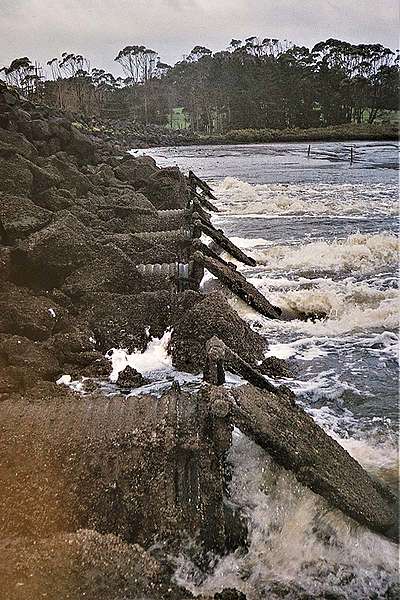

The hikoi travelled to the crystal-clear source of the river at Lake Tarawera, then to the Tarawera Falls, to Kawerau, to Braemar Springs, and finally to Matata Lagoon and the adjacent wetlands where the blackened polluted river runs into the sea in the Bay of Plenty.

One of the highlights of the hikoi was the blessing ceremony to lay sacred stones at the source of the river to help restore its Mauri (life-force). Pouroto Ngaropo of Ngati Awa led a karakia before the stones were placed in the river. Former Greenpeace Campaigner Gordon Jackman placed one of the stones in the river on behalf of Greenpeace. After spending the night at the Umutahi Marae, the hikoi continued at Matata Lagoon with the planting of flax as part of the local community’s lagoon and wetland restoration project with local community campaigners Warren and Kay Smith.

A few weeks later, the Bay of Plenty regional council organised the first Resource Management Act (RMA) consent hearings for the Tasman pulp and paper factory’s application to discharge its toxic effluent into the Tarawera River. Greenpeace participated in the hearings, represented by Legal Counsel Duncan Currie, alongside local community and iwi members. Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo submitted that the council should only issue short-term consents requiring the effluent discharge to be phased out to zero by the year 2000.

In early 1998 the Bay of Plenty regional council agreed instead to issue a 15-year consent with a range of new conditions, including a clause requiring the factory’s discolouration of the river to be cleaned-up and progress reviewed in 2005. Although it was a flawed decision which would permit the company to continue polluting the river for another 15 years, it had the effect of forcing the company to substantially clean-up by reducing its effluent discharges into the river over that period. It also fell well short of the 35-year consent the company had applied for.

Regulating toxic waste

The National-NZ First Coalition Government had established a Hazardous Waste Advisory Group (HWAG) in 1996 on which Greenpeace was represented by Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo. The HWAG recommended a raft of toxic waste regulations and reporting requirements for industry in 1997.

After the National-NZ First Coalition Government fell apart in 1998, the stated agenda of pursuing a phase-out of organochlorine pollution and the regulation of toxic waste ground to a halt under the remnant National Government that was led by Jenny Shipley in its final year in office. A change of government followed with the election of Helen Clark’s Labour-led Coalition Government in 1999.

A weaker approach to toxic waste regulation and pollution eventuated in the form of “hazardous waste guidelines” for the identification and reporting of hazardous wastes published by the Ministry for the Environment in 2002. This was a sign that the new Environment Minister Marion Hobbs and the environment ministry’s thinking had been captured by industry views.

There was eventually some good news in the form of $9 million in government funding to pay for the clean-up of contaminated sites, announced in 2003.

The following year the ministry announced weak National Environmental Standards for Air Quality under the RMA. This prompted Greenpeace to warn that New Zealanders would still be at risk from toxic pollutants such as dioxins because the weak new standards exempted three existing toxic waste incinerators and some big industries that discharged dioxins into the air.

The hazardous waste management “guidelines” published by the environment ministry in 2004 ended up being much weaker than the regulatory approach that had been proposed by the Hazardous Waste Advisory Group in 1997.

In 1997, Greenpeace’s Toxics Campaign had started to target waste incinerators as a dioxin pollution source in Auckland, and a proposed $223 million ‘waste incineration for energy generation’ development at the mothballed Meremere coal-fired power station, which would have caused large-scale dioxin pollution from burning waste and used coal as the feeder fuel, further increasing NZ’s carbon emissions.

In June 1997 Greenpeace and iwi representatives joined with Labour MP Jill White to host a reception at the Beehive for the opening of Greenpeace’s ‘White Paper, Black River’ photographic exhibition. The photos commissioned by Greenpeace featured images of the river, local native bird and fish species, and the local people who were campaigning against pollution of the river.

In speeches at the opening event Greenpeace and iwi representatives called on the Government to rapidly implement a phase-out of toxic organochlorines and dioxin pollution.

Stopping toxic trade

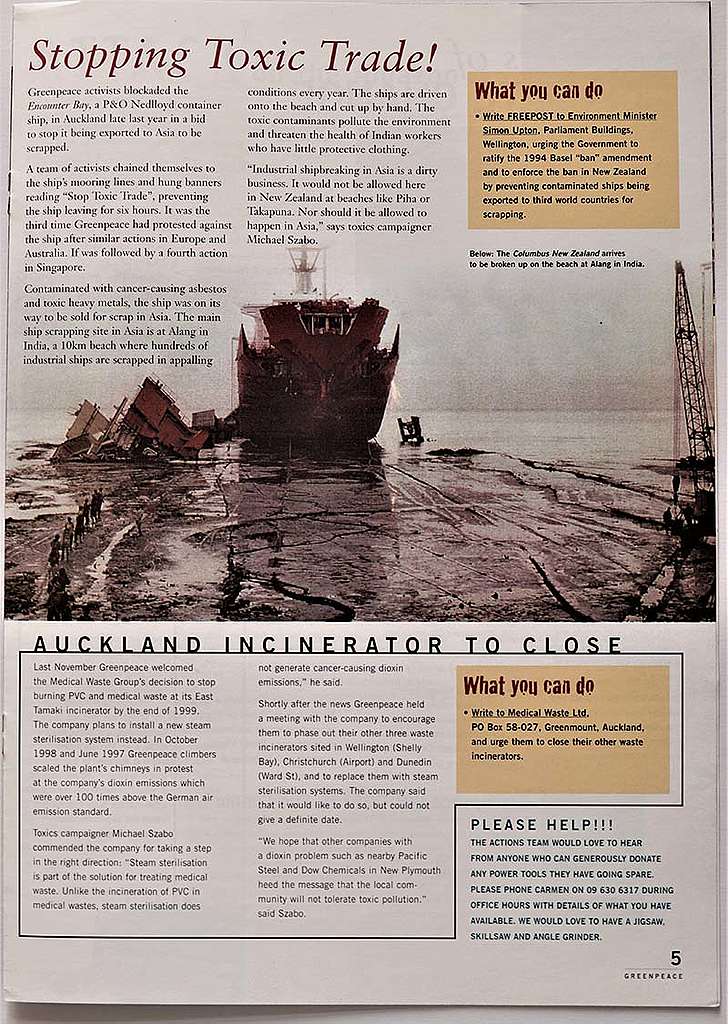

In 1998 Greenpeace also took action to oppose toxic ‘ship-breaking’, a practice in which old ships containing toxic materials such as heavy metals and asbestos were sent to India to be broken up in order to avoid having to spend the money to have the ship dismantled safely in a developed country with higher health and safety and better environmental protection standards.

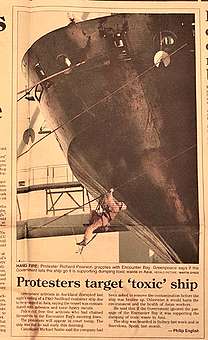

In November, Greenpeace activists chained themselves to the mooring lines of the P&O Nedlloyd container ship Encounter Bay in the port of Auckland and hung ‘Stop Toxic Trade’ banners in a bid to stop the ship being exported by its owner to Alang in India to be scrapped on a beach in appalling conditions.

The ship, which contained cancer-causing asbestos and toxic heavy metals, was held up for six hours and the action was reported on TV and radio news, and made the front page of the NZ Herald the next day.

Industrial ship-breaking at Alang involved driving hundreds of ships every year up onto a 10km stretch of beach and then cutting them up by hand in appalling conditions. The contaminants they contained polluted the local environment and threatened the health of the workers who had little protective clothing. At the time, Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo said, “Industrial shipbreaking is a dirty business that would never be allowed to happen on beaches in New Zealand like Takapuna or Piha. Nor should it be allowed to be done like this anywhere else.”

Greenpeace also urged the NZ Government to ratify the 1994 Basel Convention toxic waste export ‘ban’ and enforce it by banning contaminated ships such as Encounter Bay from being exported to less-developed countries for scrapping. New Zealand is still one of only a few industrialised countries that has not ratified the ban in 2020.

Deadly Legacy tour

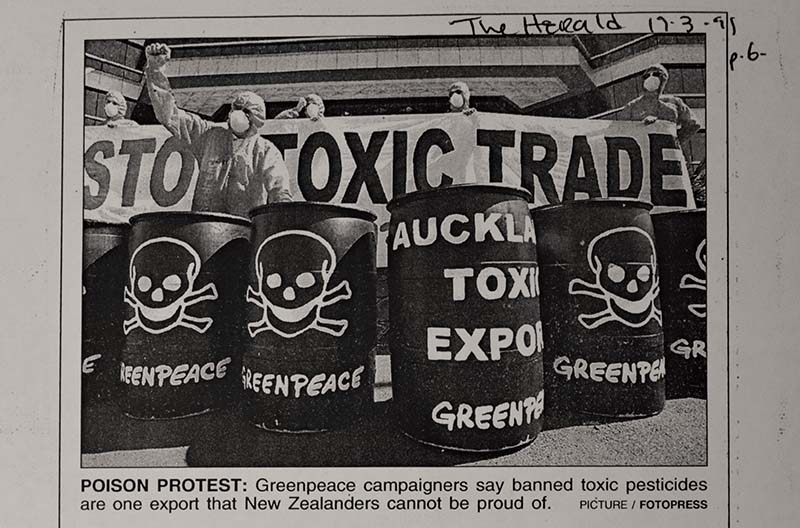

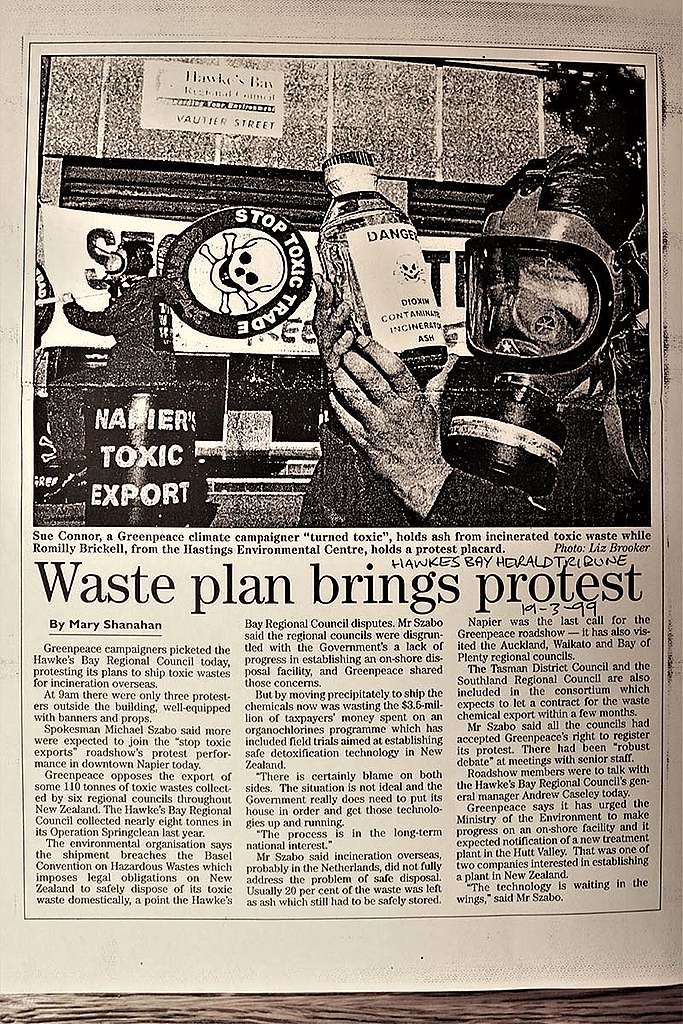

In 1999 Greenpeace activists organised a Deadly Legacy tour targeting regional council offices and the Ministry of Commerce head office with mocked-up barrels of toxic waste and banners, and loudly demanded a halt to the planned export of unwanted toxic agricultural pesticides to Europe for dirty incineration.

Greenpeace demanded that the unwanted agricultural chemicals should instead be placed into safe storage and the councils wait for the availability of a new safe dechlorination technology that had by then been successfully trialled by the Ministry for the Environment. Doing so would have helped make a clean-up of NZ’s many toxic contaminated sites happen sooner, more safely, and in a more cost-effective way.

At the time the Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Hawkes Bay, and Southland regional councils plus Tasman District Council were hell-bent on exporting the 110 tonnes of unwanted pesticides that they had collected from NZ farmers to a polluting waste incinerator in the Netherlands. Burning the toxic chemicals would lead to the discharge of cancer-causing dioxins into the air and leave residual dioxin-contaminated ash waste that still needed to be safely disposed of, warned Greenpeace.

A 1992 report published by the Ministry for the Environment had even estimated that there were up to 8,000 contaminated sites in NZ. Informed estimates also predicted there were still hundreds of tonnes of unwanted toxic agricultural pesticides and herbicides to be collected and thousands of tonnes of contaminated waste and soil from pulp factory sludge to contaminated soil that also required treatment in NZ.

A few months after Greenpeace’s ‘Deadly Legacy’ tour, the National Government approved the export of the chemicals and they were shipped to The Netherlands to be burned. Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo says that by doing so they put back the availability of a safe clean-up technology in NZ for another five years until a subsequent Labour-led Coalition Government funded a $9 million clean-up fund. For example, that allowed the Ministry for the Environment to organise and fund a clean-up at the most contaminated site, Mapua, in the Tasman District.

Ban the Burn

Greenpeace’s campaign against waste incineration and for a clean-up of contaminated sites continued through the 1990s into the 2000s with a series of actions targeting waste incinerators in Auckland.

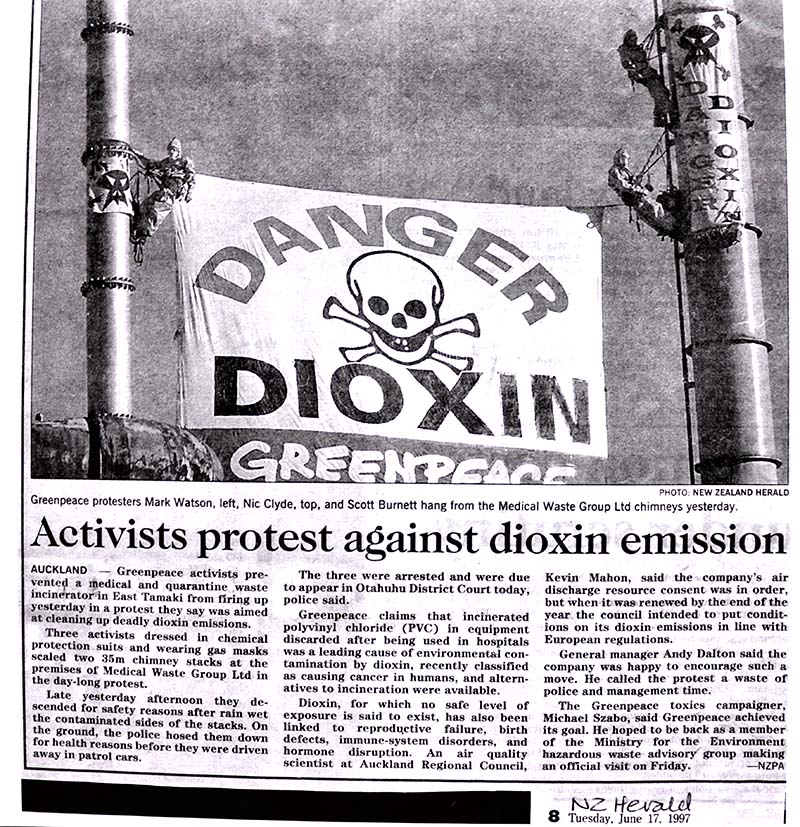

In June 1997 a team of Greenpeace activists scaled two 30-metre industrial chimneys at a South Auckland medical waste incinerator to hang a large banner between the chimneys that read: ‘Danger Dioxin’.

A second team chained themselves to vans parked in front of the incineration factory’s service entrances to prevent any PVC waste being delivered, and another activist chained themself to the factory’s front door. Together they stopped the incinerator’s regular Monday morning start-up.

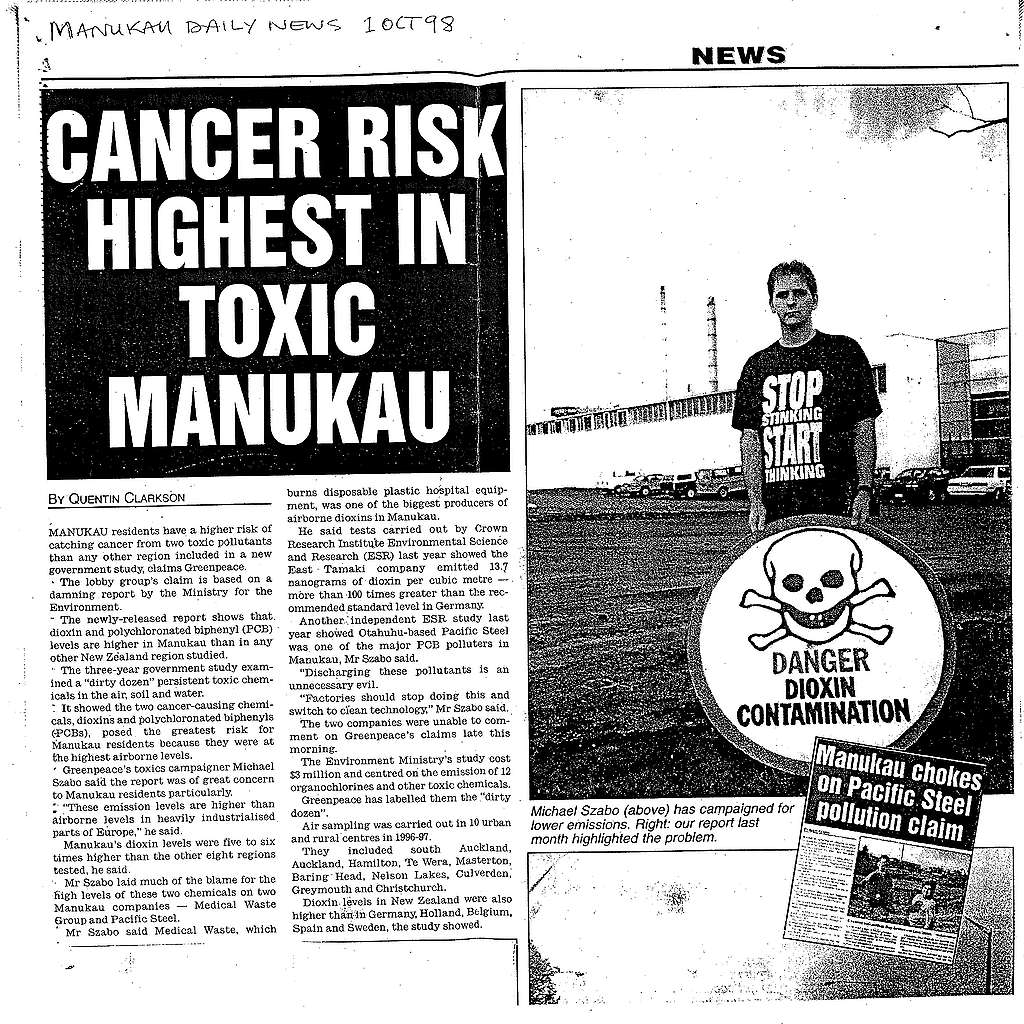

“We targeted it after Auckland Regional Council test results found it was discharging dangerous cancer-causing dioxins into the air at a level 137 times above the German air emission standard,” said Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo. At the time, dioxin had recently been classified as a pollutant that could cause cancer in humans.

Greenpeace called on the company to switch to the safer alternative of enclosed steam sterilisation of medical waste or ‘autoclaving’.

In October 1998, Greenpeace activists once again targeted the same medical waste incinerator in East Tamaki because its reported dioxin emission rate had risen by more than 200% from 3.8 nanograms per cubic metre of air to 13.7 nanograms. They hung a giant banner from the chimney stacks that read, ‘Cancer Prevention by Greenpeace’.

At the time, South Auckland had the highest airborne dioxin levels in New Zealand according to the Ministry for the Environment, higher than anywhere in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Sweden and Australia. The incinerator was located close to a residential area in Otara, to the local Mayfield Primary School, and to the local Fisher & Paykel factory which had 1,500 workers.

The following month Greenpeace welcomed the Medical Waste Group Ltd’s announcement that it would close its East Tamaki waste incinerator in 1999 and install a new state-of-the-art enclosed steam sterilisation system to replace it, as Greenpeace had been demanding.

At a meeting with the company shortly afterwards, Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo urged them to switch to steam sterilisation at all of their incinerater sites in Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin

“While Greenpeace cautiously welcomes this as a step in the right direction the company still needs to close its three other medical waste incinerators in Wellington, Christchurch, and Dunedin,” said Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo.

The company said that it agreed, but that it could not give a definite date. The company’s Wellington medical waste incinerator in Evans Bay, Miramar, was subsequently closed and replaced with a new steam sterilisation unit in August 2001.

In October 1999 Greenpeace celebrated news that the proposed $223 million waste incineration–energy generation scheme using the moth-balled 210-megawatt Meremere coal-fired power station in the Waikato had been rejected after a two-year campaign against it that brought together Greenpeace and a coalition of local residents and farmers, North Waikato Environmental Group, River Watch, the Recycling Organisations of New Zealand (RONZ), and Friends of the Earth NZ. The proposal had also been opposed by the Tainui Corporation, Huakina Development Trust, Ministry for the Environment, Auckland Regional Council, Manukau City Council, and Waitakere City Council.

By helping to stop the proposed waste incineration scheme from burning a million tonnes of municipal solid waste per year, Greenpeace had helped prevent a huge new source of toxic dioxin emissions from starting up. “If it had gone ahead it would also have created huge carbon emissions from burning coal as its feeder fuel and burning a vast amount of wood, cardboard, paper and plastic,” said Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Michael Szabo, who ran the Greenpeace campaign with Climate Campaigner Adam Laidlaw.

Michael Szabo worked for the UK Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and Greenpeace UK before moving to New Zealand. He wrote Making Waves: The Greenpeace New Zealand Story (Reed Books) in 1991, and worked as a journalist writing for New Scientist, Sunday Star Times, and New Zealand Geographic. He was Greenpeace New Zealand’s Campaigns Manager, Communications Manager, and Toxics Campaigner 1994-99.

Since then he has worked as Communications Manager for BirdLife International in the UK and for Forest and Bird in New Zealand, as founding Director of Pew Environment Group’s Kermadecs Ocean Sanctuary project in NZ, as Communications Manager for the Engineering, Printing & Manufacturing Union, editor of Forest & Bird magazine, and editor of Disarmament Diplomacy journal. He has also worked for Te Papa on its New Zealand Birds Online website project, as Communications Adviser for the Tertiary Education Union, and been editor of Birds New Zealand magazine (Ornithological Society of NZ) since 2016. He worked on the Greenpeace New Zealand History Project 2019–2020.

The POPs Treaty

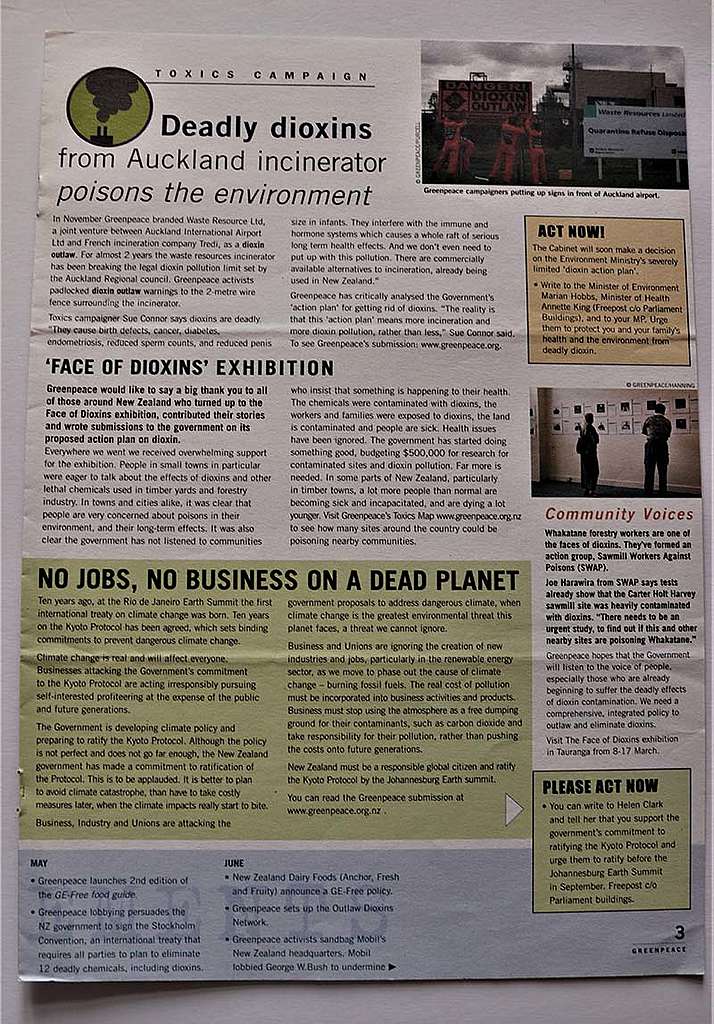

In October 2000 Greenpeace organised a five-week ‘Eliminate Dioxin Drive’ to highlight the extent of dioxin pollution in New Zealand in communities with waste incinerators and contaminated sites, and called on the Government to eliminate dioxin pollution and clean-up contaminated sites.

“We are launching the ‘Eliminate Dioxin Drive’ at one of New Zealand’s many dioxin polluting sites, the Christchurch Medical Waste Incinerator operated by the Medical Waste Group Ltd,” said Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Sue Connor.

The tour also included a new exhibition called “Faces of Dioxins” and specially produced postcards urging the Minister for the Environment to phase-out dioxin pollution. Greenpeace also helped put dioxin pollution on the map with the launch of a powerful new database-driven website highlighting dioxin sources and contaminated sites around the country.

Greenpeace also joined with local people from dioxin contaminated communities in Whakatane, Kawerau, Matata, and New Plymouth who presented their testimonies about toxic pollution and site contamination to MPs at the Beehive at the opening of the “Faces of Dioxins” exhibition there.

In March 2005 Greenpeace joined with Sawmill Workers Against Poisons (SWAP), Vietnam Veterans of Aotearoa, Paritutu Dioxin Investigation Action Group, and Te Waka Kai Ora (Māori organics group) to organise a series of ‘Hohou te Rongo – People Poisoned Daily’ public meetings in communities impacted by toxic dioxin contamination in Whakatane, Rotorua, New Plymouth, Whanganui and Wellington.

In 2001, having not initially supported the wording of a proposed new treaty, the NZ Government committed to signing the new Stockholm Convention on ‘Persistent Organic Pollutants’ (POPs).

Greenpeace joined with Bay of Plenty iwi, and community groups including Millwatch, Sawmill Workers Against Poisons (SWAP), Dioxin Investigation Action Group (New Plymouth), and Residents Against Incinerator (Wellington) to welcome the change of heart and called on the Government to implement a phase-out of dioxin pollution across NZ.

It was not until February 2004 that Minister for the Environment Marion Hobbs announced that the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) would come into force in New Zealand in May 2004.

Greenpeace welcomed the news and reminded the Minister of the need to rapidly implement phase-out dioxins. “The Government must not sidestep the Convention’s ultimate aim of eliminating dioxins. There is no proven safe level of dioxins”, said Greenpeace Toxics Campaigner Mere Takoko (Ngāti Porou). “If implemented properly, the Stockholm Convention – which aims to eliminate poisons that can lead to cancers and reproductive disorders – will have a beneficial impact on our environment and everybody living in New Zealand.”

There was also the deadly legacy left by decades of toxic organochlorine pesticide production, storage, and use at Mapua by the Fruitgrowers’ Chemical Company (1945-88) that still needed to be cleaned up.

The main contaminants at the site were toxic organochlorine pesticides, such as DDT, Dieldrin and Lindane, also known as POPs. Greenpeace was critical of the inadequate proposed site containment option and argued instead for the soil to be decontaminated using a state-of-the-art dechlorination process that treated and neutralised the contaminants rather than simply ‘containing’ them on-site.

Site investigations were carried out prior to a resource consent application to clean up the site in 2003. Greenpeace joined Forest and Bird’s appeal of proposed weak consent conditions, which led to an improved consent being issued in November 2003. The Ministry for the Environment became the consent holder in August 2004 and used an on-site ‘Mechanochemical Dehalogenation’ facility to dechlorinate and neutralise the contaminants in the soil. The clean-up was finished in July 2007.

The Labour-led Coalition Government also set up a Contaminated Sites Remediation Fund administered by the Ministry for the Environment in 2003 which is used to help regional councils investigate and clean-up contaminated sites.

Greenpeace continued to oppose waste incineration. A team of activists scaled the chimney of the Auckland airport waste incinerator and attached a metal lid to prevent it from burning waste in 2002. It was the largest waste incinerator in the country and probably the largest single dioxin source in NZ at the time. Following this action, Greenpeace joined with Nga Manga, a network of South Auckland community groups, to demand the closure of the incinerator and its replacement with an enclosed steam sterilisation plant.

In February 2003 Greenpeace welcomed the announcement that the Christchurch airport waste incinerator would be closed and replaced with an enclosed steam sterilisation plant, which followed the publication of an open letter in the Christchurch Press and hundreds of emails from Greenpeace supporters urging the company to do so.

This meant that all the other medical and quarantine waste incinerators in the country – in Auckland, Dunedin, Wellington, and now Christchurch – had now either closed, or announced their closure, to be replaced by enclosed steam sterilisation.

In April 2003, Greenpeace activists blocked trucks carrying quarantine and medical waste from entering the waste incinerator site at Auckland airport and hung a banner on the building that read, “Stop Poisoning Us – Stop Incineration”. Greenpeace also called on the Government to ban waste incineration.

The following year the Government adopted weak Air Quality Standards that exempted existing hazardous waste incinerators such as one at the Dow herbicides factory in New Plymouth and industries that burned waste such as metal smelting plants and cement kilns, which also emitted dioxins.

Finally, in July 2005, the operator of the Auckland airport waste incinerator signed an agreement to replace it in 2006 with a state-of-the-art enclosed steam sterilisation unit. Greenpeace welcomed the news that the largest waste incinerator in the country was at last going to close down after a decade of campaigning against dioxin pollution from waste incineration.

In the years after the Stockholm Convention on POPs was ratified, Greenpeace had been instrumental in closing down four large waste incinerators and persuading the Government to start cleaning up organochlorine and dioxin contaminated sites.

Greenpeace’s Toxics Campaign was wound down in 2005 at a time when the whole global organisation was becoming even more strongly focused on phasing-out fossil fuels, combating climate change, and protecting the world’s oceans.

Tarawera River post-script

Following the 2005 review of the Tasman Pulp and Paper Company’s resource consent conditions for discharging into the Tarawera River, the company was required to make further process changes to reduce the amount of pulp effluent it discharged into the Tarawera River in order to improve the clarity of the lower river and dissolved oxygen levels.

The Kawerau factory’s Chlorine Dioxide bleaching unit subsequently closed in April 2019 after which it produced only unbleached ‘brown pulp’. The change meant that its pulp effluent was no longer discharged into the river, but instead into on-site evaporation ponds. Then in 2021 the company’s new owner, Norske Skog, announced the factory would close down.

Contaminated sites cleaned-up

In the years since their time as Greenpeace campaigners during the 1990s, Catherine Delahunty and Gordon Jackman continued to work for a clean-up of toxic contaminated sites, in Catherine’s case as a Green MP from 2008 to 2017, and in Gordon’s case on the board of Greenpeace NZ which he chaired (2000-2002), and in a personal capacity.

As a result, successive governments have funded more contaminated site clean-ups, including former timber treatment sites such as Kopeopeo Canal in Whakatane which was heavily contaminated with PCP and dioxin from a nearby timber treatment site from the 1940s to the 1980s.

New Plymouth agricultural chemical factory closes down

In August 2020 the chemical manufacturing company Corteva announced it would close its agricultural chemical factory in New Plymouth in 2021. Between 1962 and 1987, the factory had been operated and owned by Ivon Watkins, later called Ivon Watkins Dow, to manufacture most of the toxic organochlorine herbicide 2,4,5-T that was sprayed in New Zealand. One of the by-products of 2,4,5-T manufacturing was dioxin, a known cause of cancer.

When the herbicide 2,4,5-T was mixed with another organochlorine herbicide manufactured at the factory called 2,4-D, they formed the chemical defoliant known as ‘Agent Orange’, which was sprayed extensively over Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia by the US military during the war in Vietnam (1965-1975).

The closure of the factory in New Plymouth also meant the on-site toxic waste incinerator which had been used for decades to burn toxic chemical manufacturing wastes was also closed down.

The news of the closure came 35 years after Greenpeace first blockaded the factory in 1985 to protest against the manufacture of 2,4,5-T there.

These companies that poisoned local people, workers, and the environment for profit got a free ride under successive New Zealand governments and councils for far too long. The government agencies responsible for workplace safety, public health, and protecting the environment also dragged the chain when they should have acted more urgently and decisively.

The lessons are the same as with the history of the use of fossil fuels: delaying action to cut emissions ends up costing more – more people’s lives and health, more environmental damage, and more money.